We produce comprehensive data to help you understand attitudes toward migration in Europe.

Our Observatory is the first of its kind:

- It describes attitudes to migration across the European Union, looking at both regional, and country-specific trends.

- It explains how attitudes vary across countries, time, and different groups of citizens and how individual’s attitudes change over the course of their life.

- It provides robust causal explanations for these variations.

The observatory uses the fullest range of public and private data, produces primary sources of data, and collates data to create more nuanced understandings of public attitudes.

About the Observatory

The observatory was established in 2017 to understand:

- How do public attitudes to immigration vary across countries, and how have they changed over time?

- What are the determinants of people’s views on migration and different types of migrants?

- What are the characteristics and determinants of people’s preferences with regard to migration, asylum, and integration policies?

- What are the implications for the politics and governance of migration and asylum?

Watch our launch event that took place in Brussels.

Factors that Influence Attitudes to Immigration

Use our data hub to explore the evidence on attitudes to immigration. While there have been theories and data, no one has been able to draw strong conclusions on the factors that affect people’s attitudes toward immigration. We address that gap.

- Our research analyzed hundreds of scientific articles and more 144 studies on individual-level factors affecting attitudes to immigration.

- We found that are two individual characteristics that are most closely tied to what a person will think about immigration: education and age.

- Our findings give policymakers more reliable answers as to what influences people’s views on immigration and helps researchers now what individual factors should be considered.

Read the full report here:

Understanding differences in attitudes to immigration : a meta-analysis of individual-level factors

Authors: Lenka Dražanová, Jérôme Gonnot, Tobias Heidland and Finja Krüger.

Interact with data

Explore the effect of more than 120 indicators on attitudes to immigration. This data draws on articles published in the top 20 journals in political science.

Read the full report on these indicators:

Author: Lenka Dražanová.

The indicators show the success rate in affecting general anti-immigration attitudes measured as a negative evaluation of the overall impact of immigration. Definitions used in the data:

- Indicator: individual and contextual level factors tested in the scientific literature as to their effect on attitudes to immigration.

Source: peer-reviewed scientific journal articles where the effect of an indicator has been empirically tested. - Success: whether the indicator’s influence confirms the theoretical assumptions and is statistically significantly related to attitudes to immigration.

- Success Rate: is provided by dividing the number of ‘successes’ by the total number of tests of the effect of an indicator. Generally, the higher the success rate, the more confident we are that an indicator has the hypothesized effect on anti-immigration attitudes, in terms of both direction and significance. However, the confidence also increases with the number of times the effect has been tested.

- Failure: the indicator does not show any statistically significant influence on attitudes to immigration.

- Anomaly: the indicator is significantly related to attitudes to immigration, but in the opposite direction.

Map of Attitudes

Our map shows what people in EU countries think about the importance of immigration. It uses both academic and poll companies’ surveys. You can use this to compare attitudes between countries as well as within the same country at different time points.

Explore the map

For help using the map, watch our instructional video.

The state of research on attitudes to immigration

We identify who is researching attitudes toward migration and where this research happening. We provide insights on the methods, research questions, and samples, as well as the characteristics of the authors. Interact with this analysis below or read it as a PDF.

The Content of OPAM project

1. The Structure of Research into Attitudes to Migration.

2. The Impact of Research into Attitudes to Migration.

3. The Geographic Distribution of Research into Attitudes to Migration, or: Who Studies Where?

4. Where Does Research into Attitudes to Migration Happen?

5. What Are the Ethnicities of People Researching Attitudes to Migration?

6. Gender Distribution of People Researching Attitudes to Migration.

Introduction

Below we visualize a dataset of articles about public opinion towards migration in several different ways. This work underlies the meta-analysis authored by Dražanová, Gonnot, Heidland & Krüger (2021).

How we conducted our analysis: We analysed hundreds of scientific articles to understand more about this important and growing field of research. Our sample of consists of 529 articles. To construct it, we first settled on five base disciplines – Migration and Ethnic Studies, Economics, Political Science, Psychology, and Sociology. Using the journal-rankings provided by Clarivate (JIF), SCImago (SJR), and Google Scholar, we picked the top 30 journals from each discipline. The selection was then refined to articles with a specific focus on attitudes towards migration. Information was gathered into an accessible resource that allows users to dig into the details of scientific work on attitudes to migration.

What our anlysis shows: Our analysis allows us not only to see the topics for research, but also more general questions about the composition and production of the social science scholarship on attitudes to migration. We provide insights in terms of method, research question, and sample, as well as the characteristics of the authors such as where they are based and their gender.

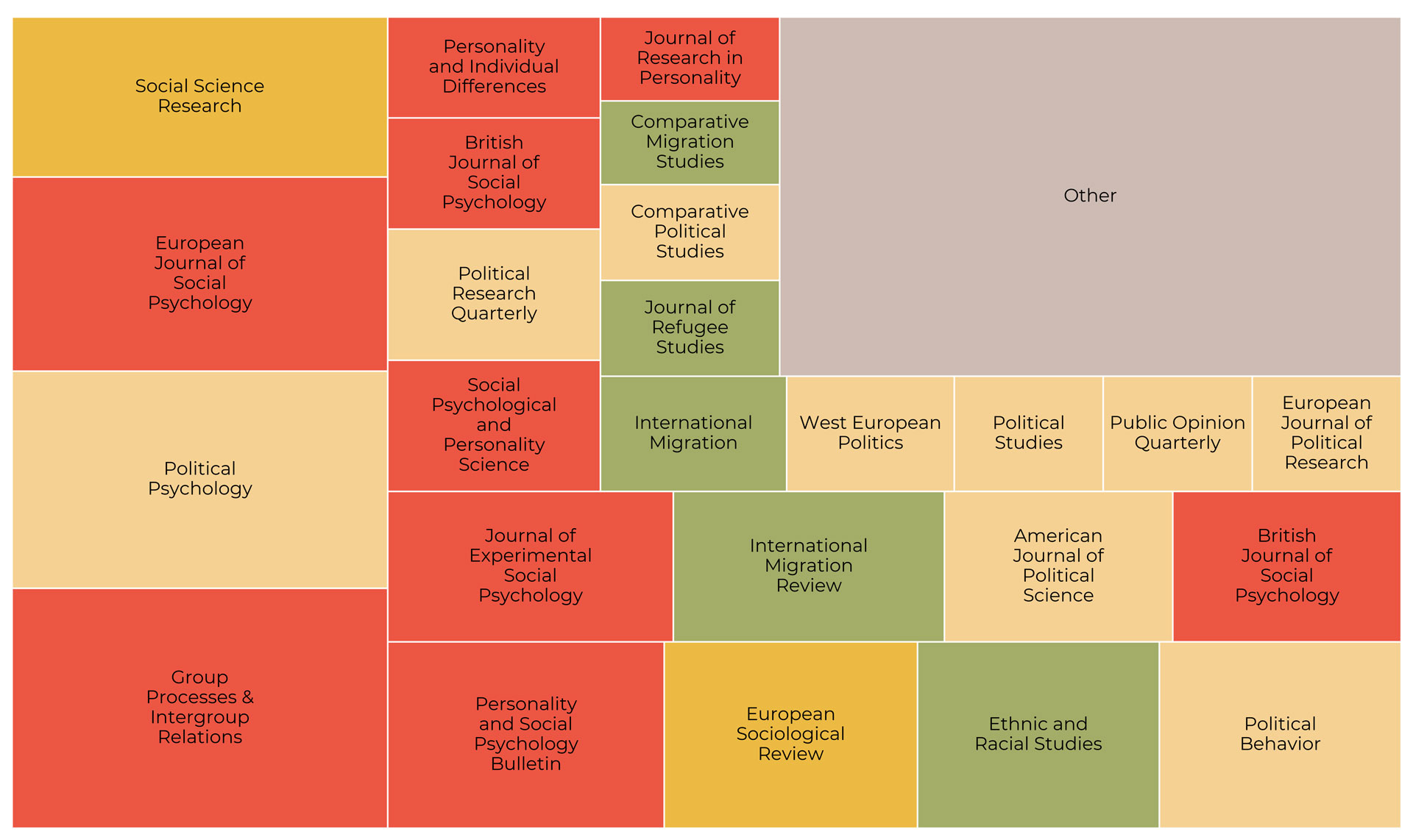

We visualize below the share that different journals proportionally take up in the final dataset.

Journal distribution within the sample

We also include a full list of the journals that ended up in our sample below:

Economic Policy, 4

Journal of Public Economics, 2

Review of Economic Studies, 1

Economic Journal, 1

Journal of International Economics, 1

Political Psychology, 38

Political Behavior, 21

American Journal of Political Science, 16

Political Research Quarterly, 13

West European Politics, 9

Political Studies, 8

Public Opinion Quarterly, 8

European Journal of Political Research, 8

Comparative Political Studies, 8

American Journal of Political Science, 6

Journal of European Public Policy, 5

Electoral Studies, 4

Socio-Economic Review, 4

JCMS-Journal of Common Market Studies, 2

Annual Review of Political Science, Vol 17, 1

Political Analysis, 1

Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 42

European Journal of Social Psychology, 34

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 20

British Journal of Social Psychology, 16

Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13

British Journal of Social Psychology, 11

Personality and Individual Differences, 10

Journal of Research in Personality, 7

International Review of Social Psychology, 5

European Journal of Personality, 5

Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3

Nature Human Behaviour, 3

Self and Identity, 2

Social Behavior and Personality, 2

European Journal of Personality, 1

Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 1

Social Science Research, 28

European Sociological Review, 22

Social Forces, 5

Social Problems, 5

Sociological Forum, 3

New Media & Society, 2

American Sociological Review, 2

American Journal of Sociology, 2

Sociological Methods & Research, 2

British Journal of Sociology, 2

Sociologia Ruralis, 1

Annual Review of Sociology, Vol 36, 1

American Sociological Review, 1

Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21

International Migration Review, 19

International Migration, 10

Journal of Refugee Studies, 8

Comparative Migration Studies, 7

Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 5

Ethnicities, 4

Journal of International Migration and Integration, 4

Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 3

Iza Journal of Migration, 2

Comparative Migration Studies, 1

Demography, 1

Journal of Population Economics, 1

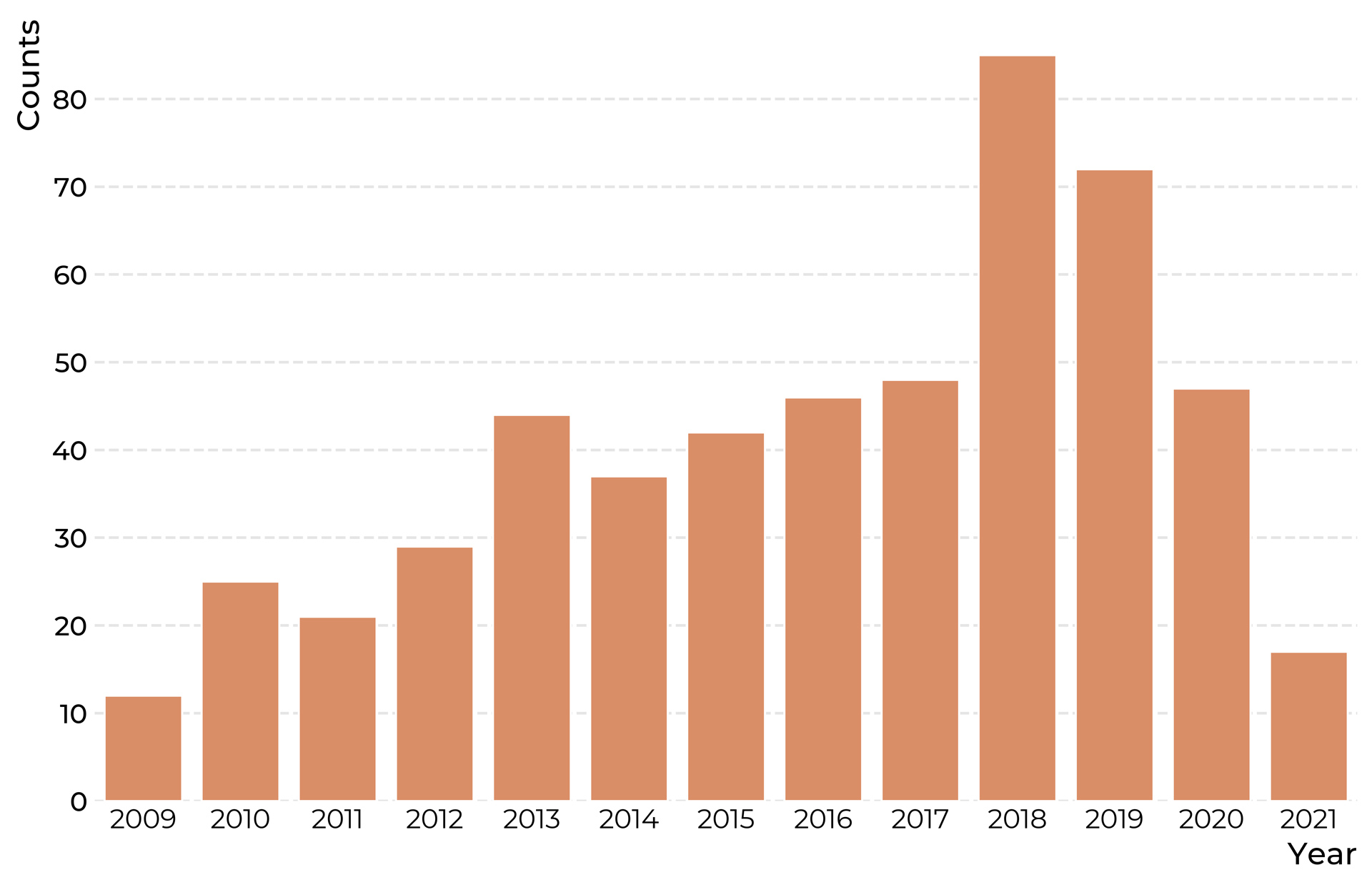

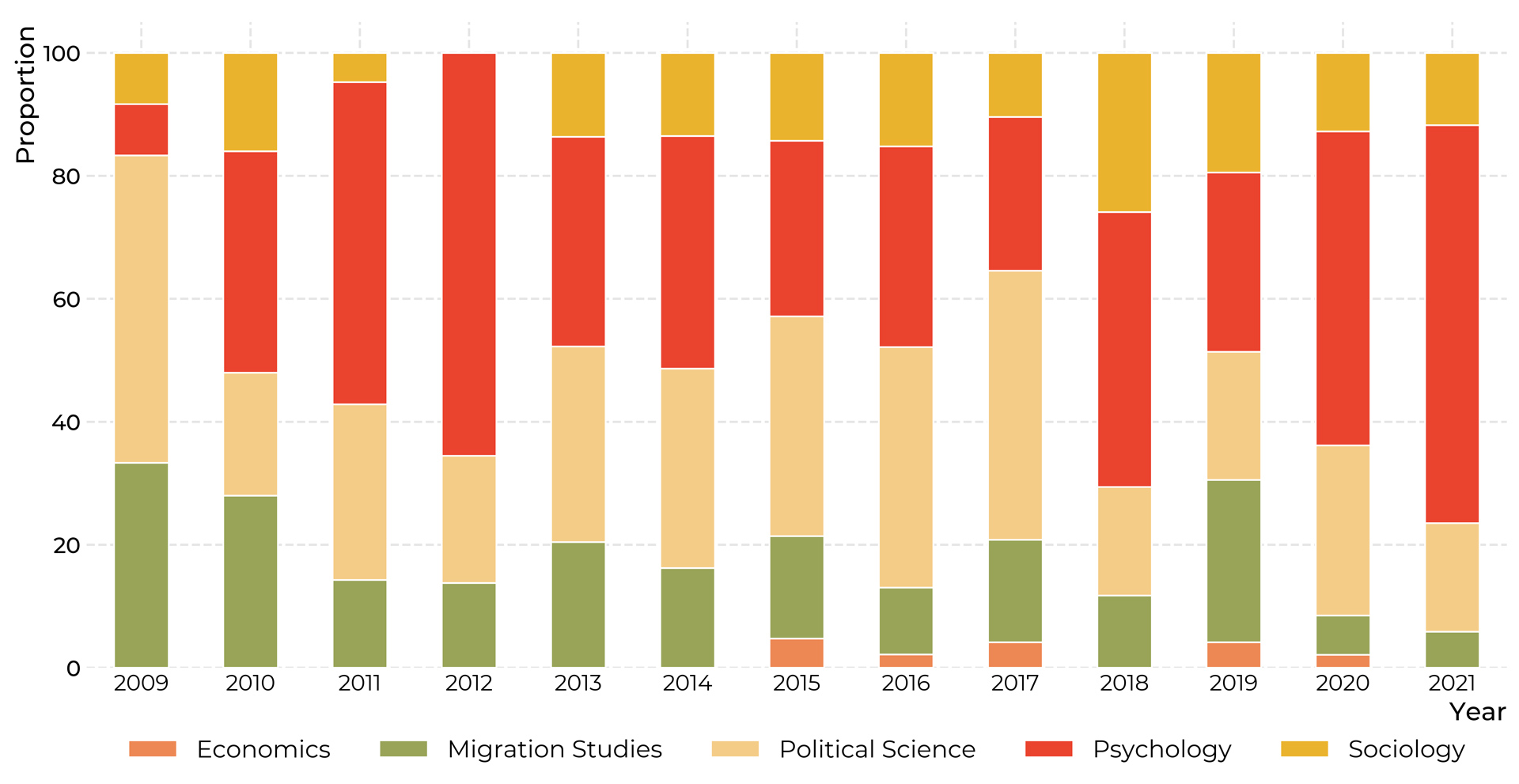

Articles to include in the dataset were then selected by searching for 'immigration' or 'immigrant' in the chosen journals. As we were interested mainly in the recent state of the field, we restricted our sample to begin in 2009, leading up to the present, in 2021. Below we show the distribution of articles over time. The small number of articles in 2021 is explained by the fact that the data collection took part before the year had run its course.

We also show the distribution of disciplines throughout the period of interest. We note that psychology and political science consistently take up a sizable share of the dataset, while only very few papers in economics were selected under our sampling procedure.

Distribution of disciplines over time

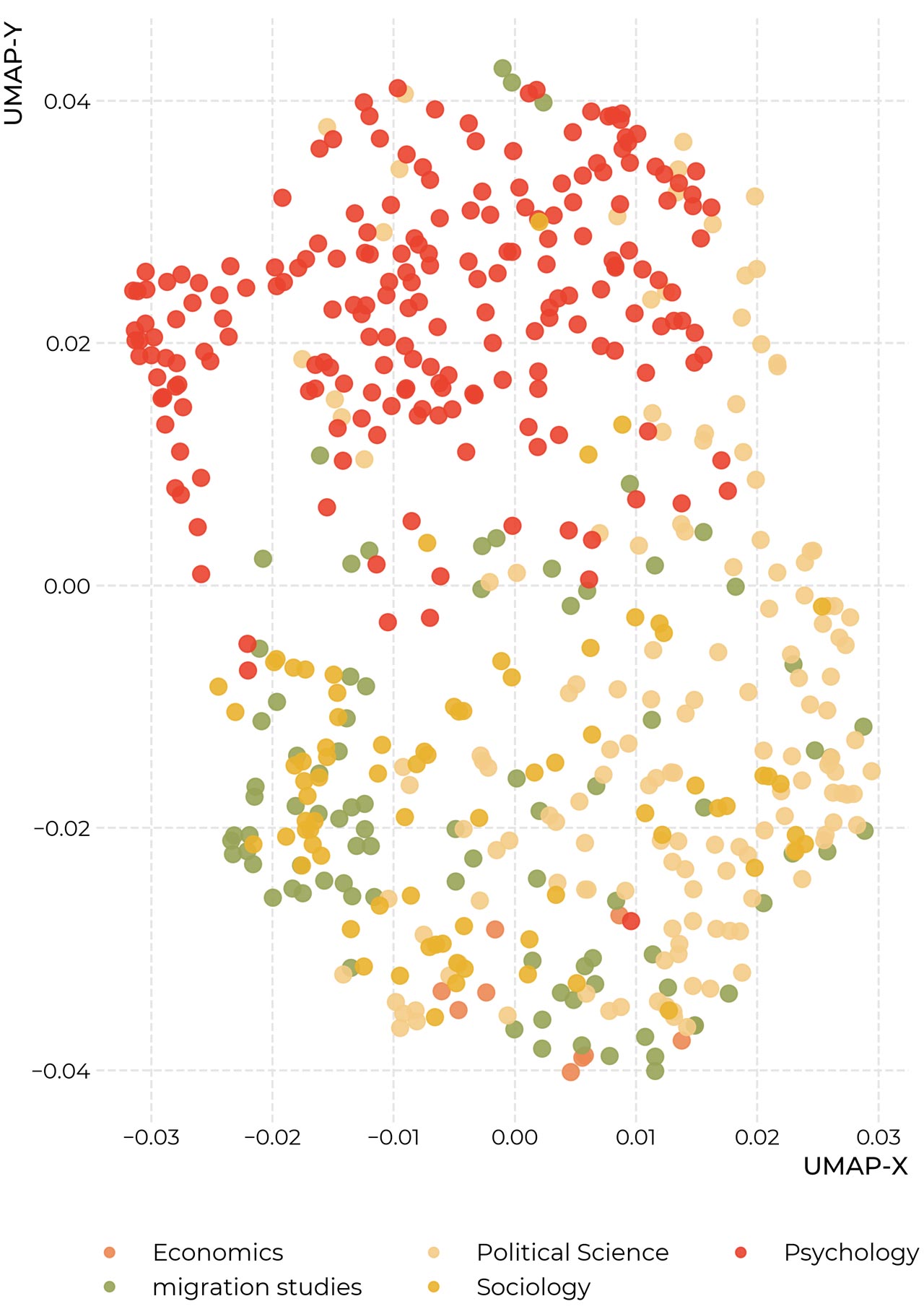

To explore our sample in much more detail, we now turn to map it using citation analysis and natural language programming techniques.

Articles, layed out by similarity in citation-patterns

Interactive explorer of 529 articles.

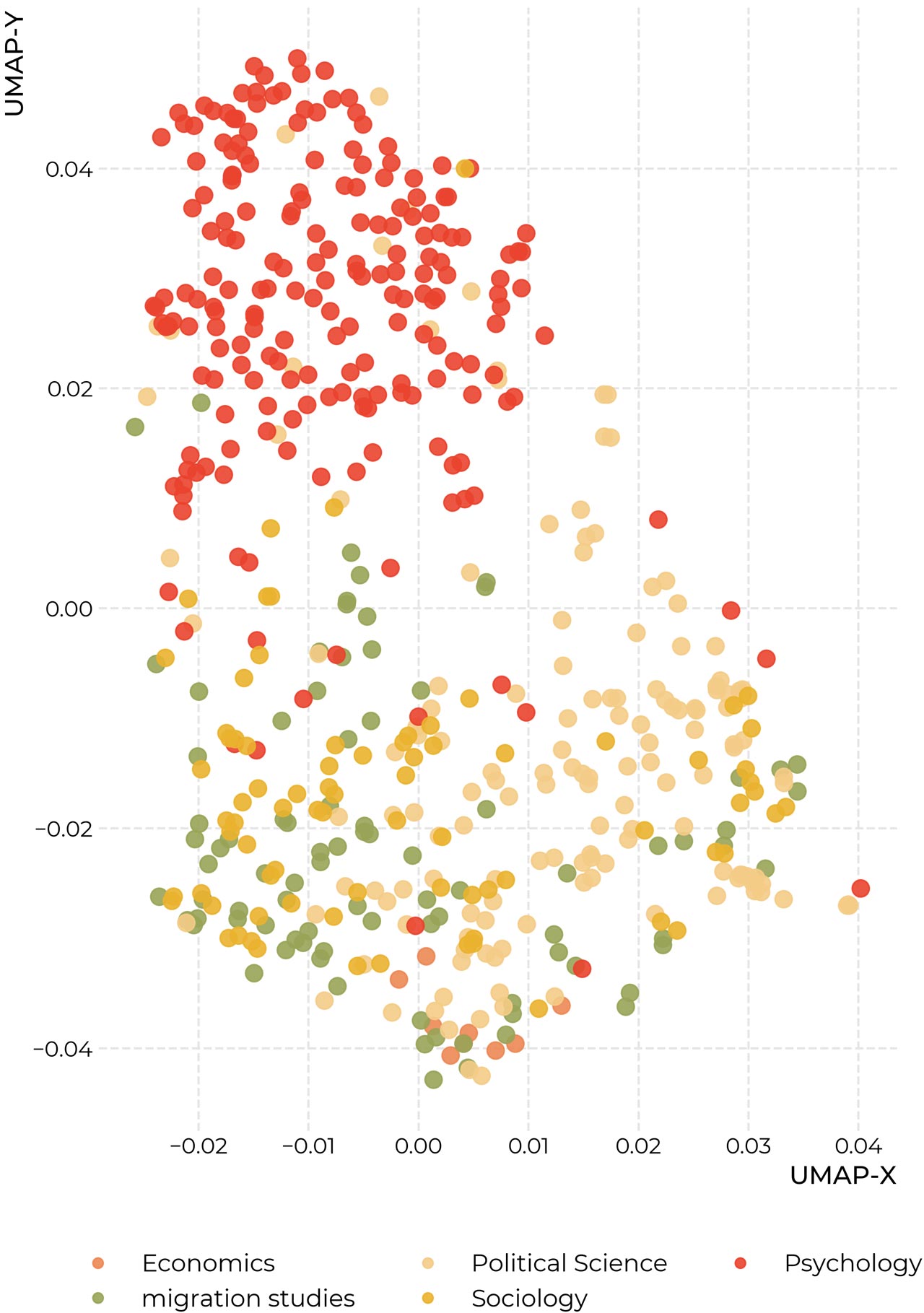

Articles, layed out by semantic similarity

Interactive explorer of 529 articles.

Articles, layed out by similarity in citation-patterns

Interactive explorer of 531 articles.

For a full functionality, please check the desktop version.

Articles, layed out by semantic similarity

Interactive explorer of 531 articles.

For a full functionality, please check the desktop version.

The two mappings above give similar views into our dataset, drawn from different sources. Each point in the mappings corresponds to one article. In the map based on citations, the distance between articles is determined by the similarity of their bibliographies. The layout is computed using a machine-learning algorithm called UMAP. Generally speaking, if an article cites the same source(s) as another one, the algorithm will try to place them next to each other. This makes for a very complicated arrangement problem: An article might for example be very similar to two others, which themselves have nothing in common, or might even, on their own, be removed very far from each other. This means, that the algorithm has to make many small trade-offs, and the mappings have to be interpreted with a certain caution. It must further be noted that the x- and y-axes can be safely ignored in these mappings, as only the relations between data-points are important.

To further ground this analysis, we provide a second view into the dataset which is based on the actual content of the articles. Here the distances between articles correspond to the similarities in the vocabulary that is used in the articles – articles that use many of the same words get moved close together. In both maps, the colors of the dots correspond to the disciplines from which we sampled the articles.

If your screen is large enough, the maps are displayed as interactive: If you hover over the dots with your mouse, you can see more details about each article, if you click on the dot, the article itself will be opened in a novel window. On the right side of the graphic, there are a variety of tools that you can use to interact with the graphic. Particularly useful is the Lasso-tool (second from above, enabled automatically). You can use it to select groups of points, and on the lower right of the graphic, the keywords will appear which differentiate the selected area most from the rest of the graphic. On the upper right side, we also provide a search bar to look for words or their parts in abstracts, titles, and names of the authors of articles.

Generally speaking, we note that both mappings seem to show a separation between articles from psychology, largely coherent towards the right side of the map, in red, and articles from sociology, political science, migrations studies, and economics, which are largely mixed, although some slight patterns appear to be visible.

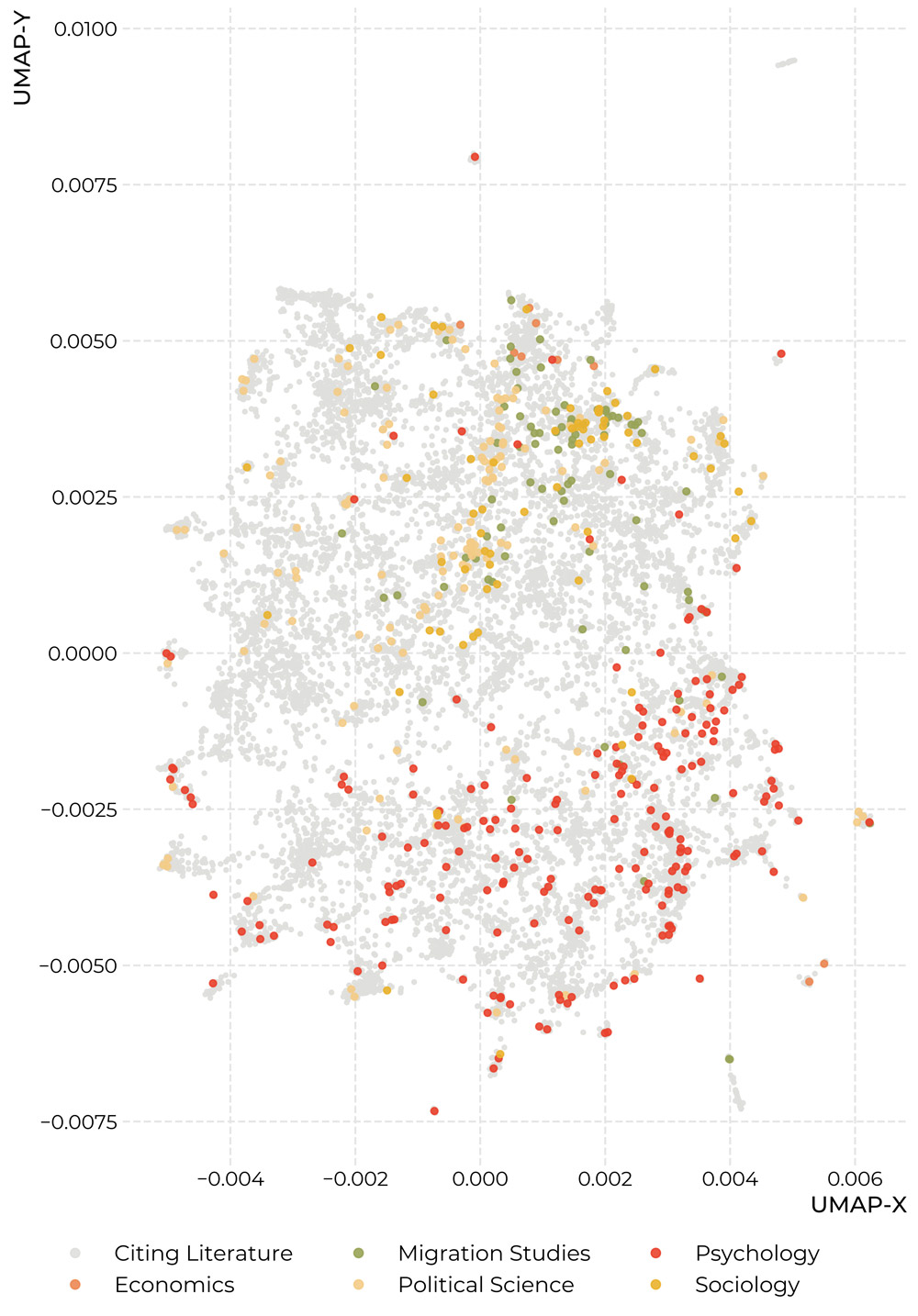

On the map below you can explore the 11.093 articles that are listed in the Web of Science as citing literature for the set of works above, as well as the articles themselves. The emerging structure can thus be interpreted as a kind of 'impact'-map for migration research. The blue lines in the background indicate the network of citations to articles in our base dataset. Again, we note two diffuse centers of psychology and the other disciplines. It also seems like psychology is more distributed over its corner of the map than migration research and sociology – which might suggest that psychological migration research is more integrated into its surrounding literature than these specific areas. But because of the tradeoffs in the production of these maps, we must urge some caution with these interpretations.

Articles, layed out by similarity in their bibliographies

Interactive explorer of 11093 articles

Location matters: to which countries does it pay attention? Where is it conducted? Where do the people conducting it come from? Based on the dataset introduced above, we try to give some answers to these questions.

To which countries does research into attitudes to migration pay attention?

To construct the map above, we went automatically over all the full texts in our dataset, looking for geographic entities using the spacy natural language programming package. We then disambiguated countries using the fuzzy-search option in the pycountry-package. The map displays the raw counts as a heatmap overlay. We can read this as a rough measurement that answers the question, about which countries the scholars in our dataset write about the most.

One important shortcoming of this method is, that it only captures concrete names of countries and large cities, but ignores regions (e.g. the Maghreb) and continents, as well as combined abbreviations (e. g. BeNeLux). If there is some systematicity in the way in which researchers talk about these geographic units, it might be lost. Nonetheless, we can hope that the precise language commonly employed in scholarly articles allows this measure to provide a useful proxy for where the attention of researchers lies.

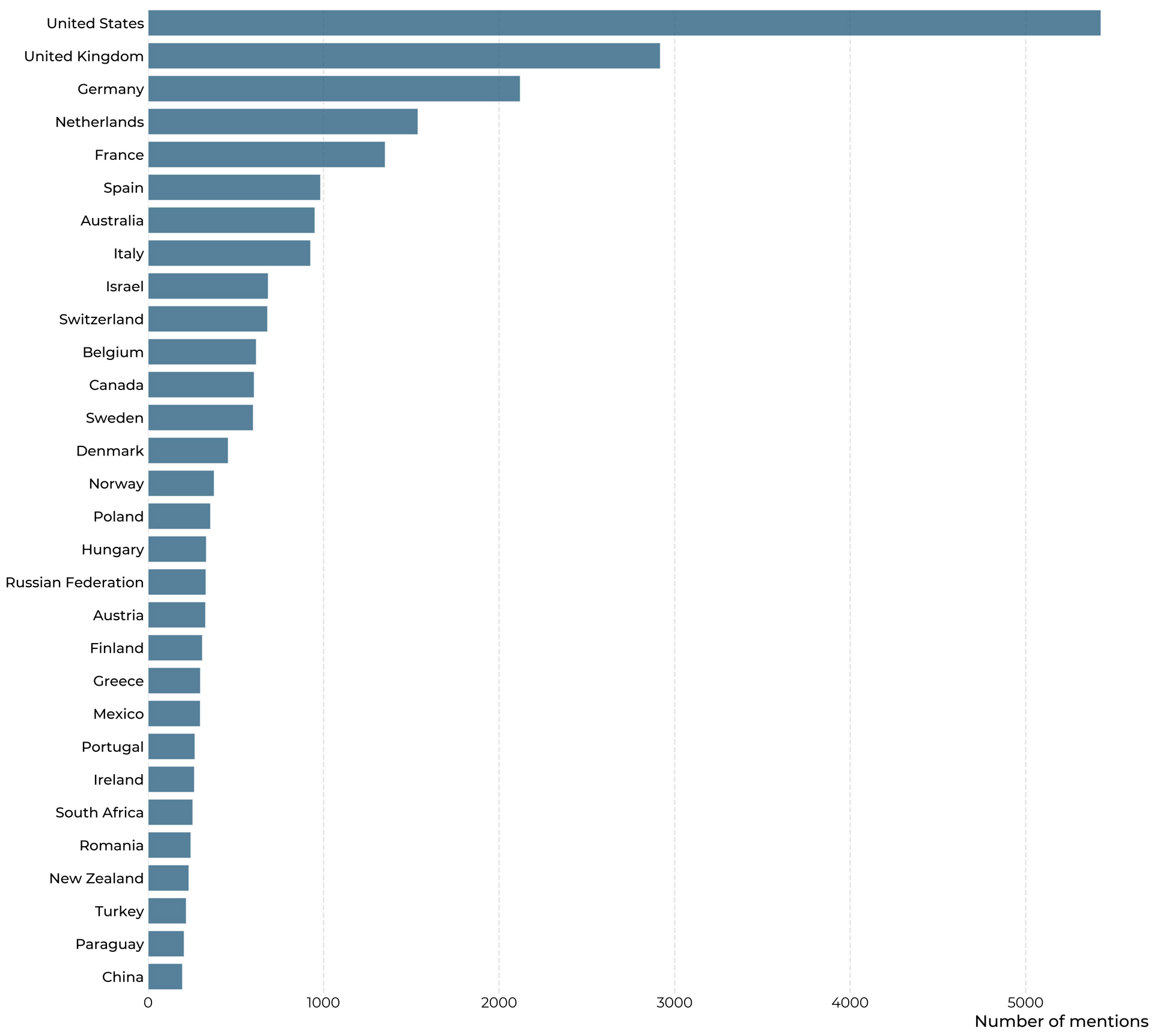

It is immediately noticeable, the United States is the country which is mentioned by far the most, followed by the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands, as well as Australia and Israel. Below we provide the counts for the most prevalent countries, for a clear comparison:

How often are individual countries mentioned by migration scholars?

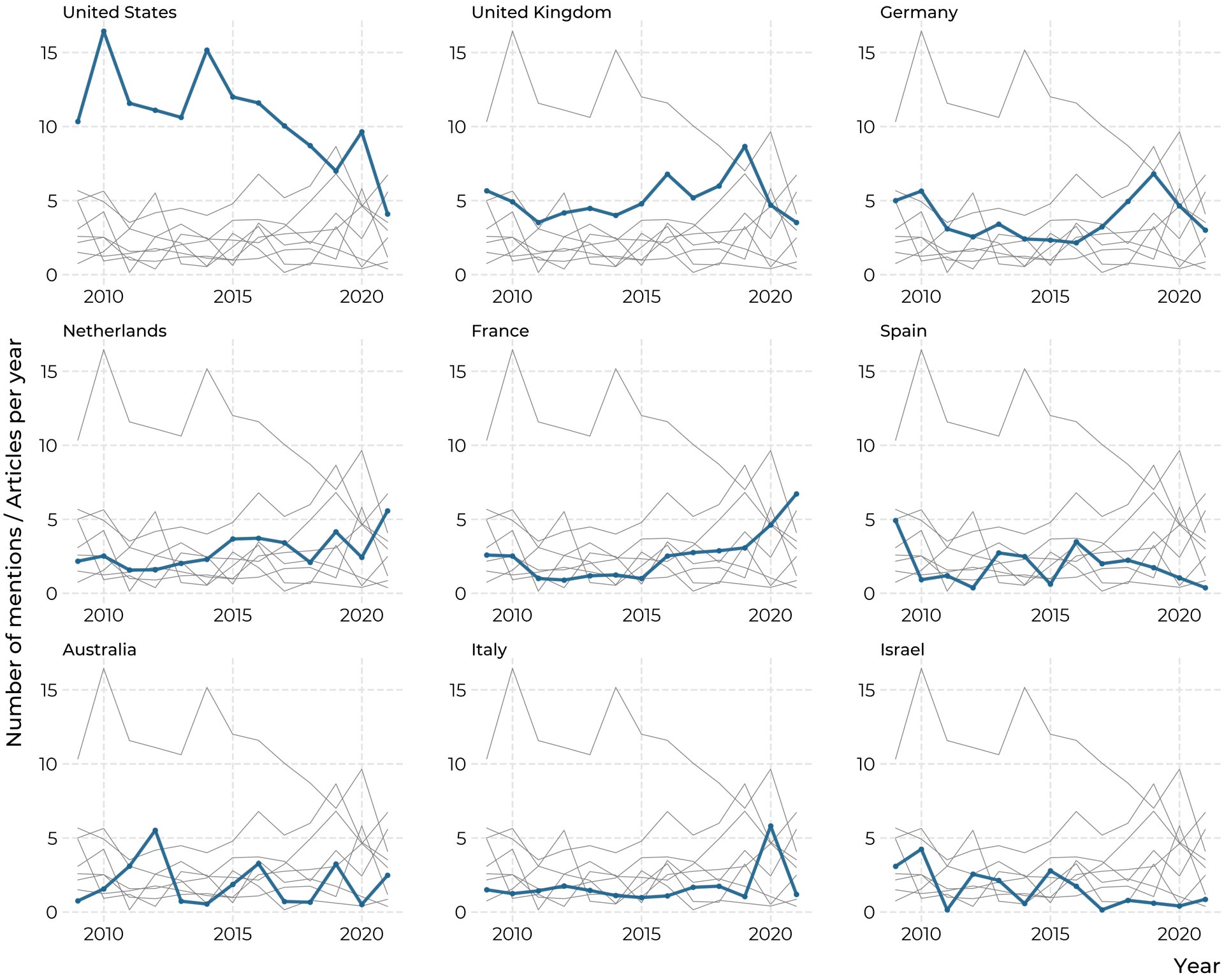

We can also take a look at how these attention patterns changed over time in the graphic below. Here counts are normalized by the number of papers in our dataset in the specific year. While the lines are very noisy, there seems to be a marked downtick of mentions of the United States in the dataset.

How has attention to countries shifted over time?

The map above shows the locations of the affiliations of researchers in our samples as circles, whose size corresponds to the number of noted affiliations. To construct the map, we went over all affiliations as they are archived in the Web of Science and extracted the city from the affiliation address, which we then used to mark on the map. Several things should thus be noted for the interpretation of the map. First, points are added for each contribution of a scientist affiliated to a specific location. So if a scientist, say at the University of Freiburg authors five papers, Freiburg receives five points. Second, multiple points are added in the case of co-authorship. Third, we disambiguate at the level of cities, not institutions. So El Paso does, for example, in the map receive points both due to the works of scientists at the University of El Paso, and Stanford University. We choose to approach the question in this way, as we are interested primarily in geographic distribution here.

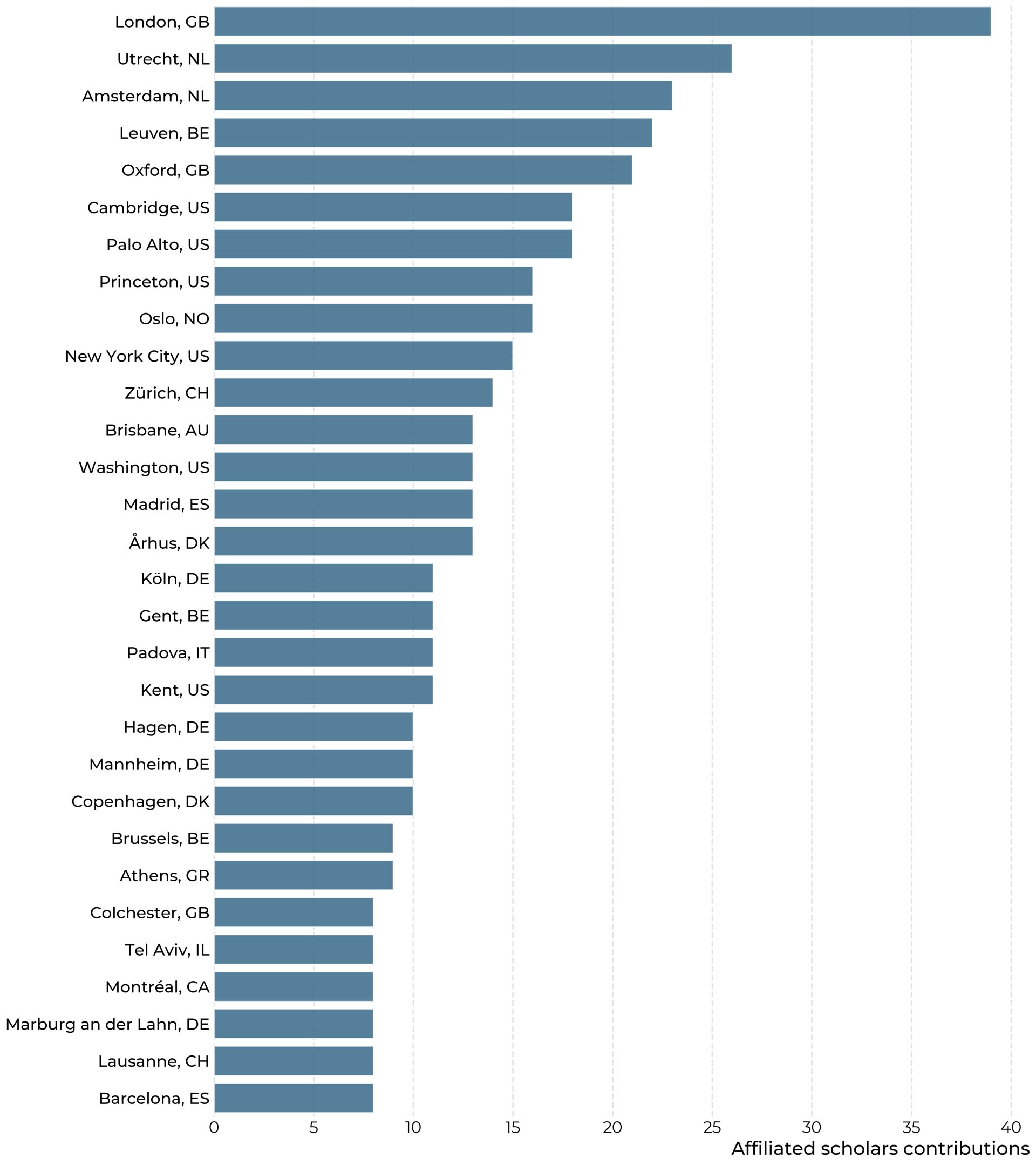

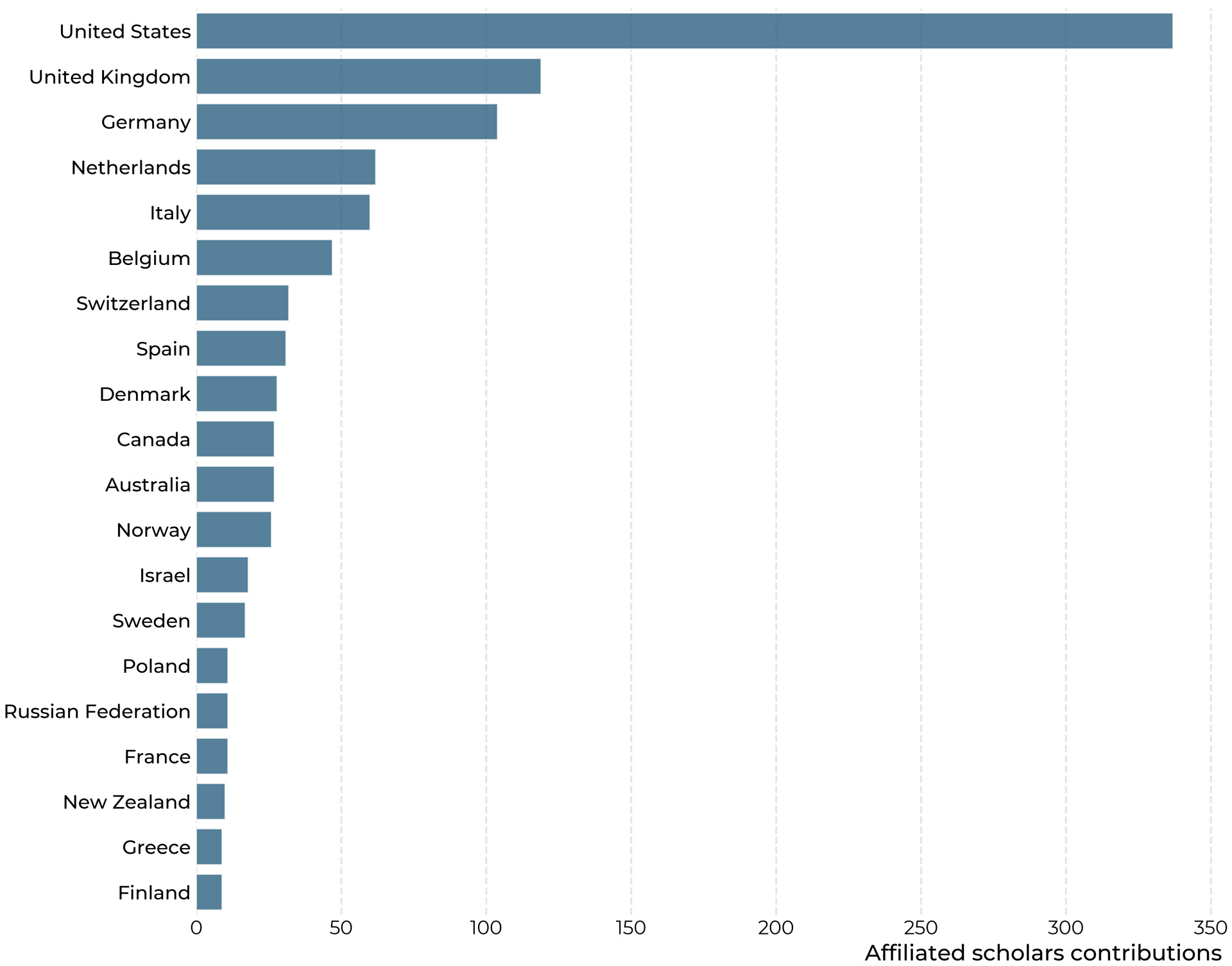

Below we also show count data, both on the level of cities, which indicates the major hubs of research into attitudes to migration, as well as countries.

Number of contributions by city of scholars affiliation

Number of contributions by country of scholars affiliation

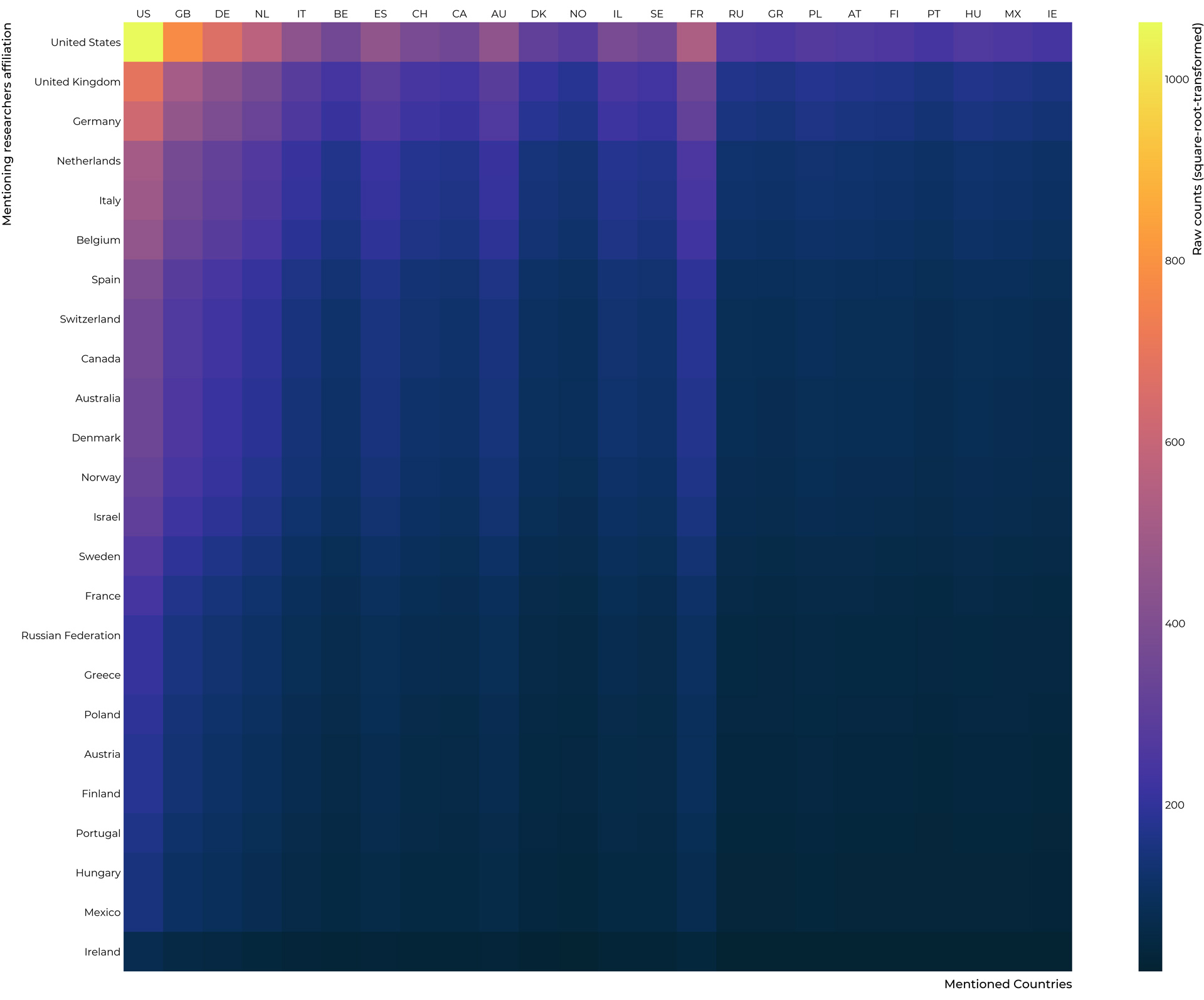

After establishing both the locations of researchers, as well as to which regions they pay attention to, it is also interesting to overlay the two datasets into one figure, which shows us how often researchers affiliated to a country in the rows of the heatmap mention countries shown in the columns.

Who mentions whom

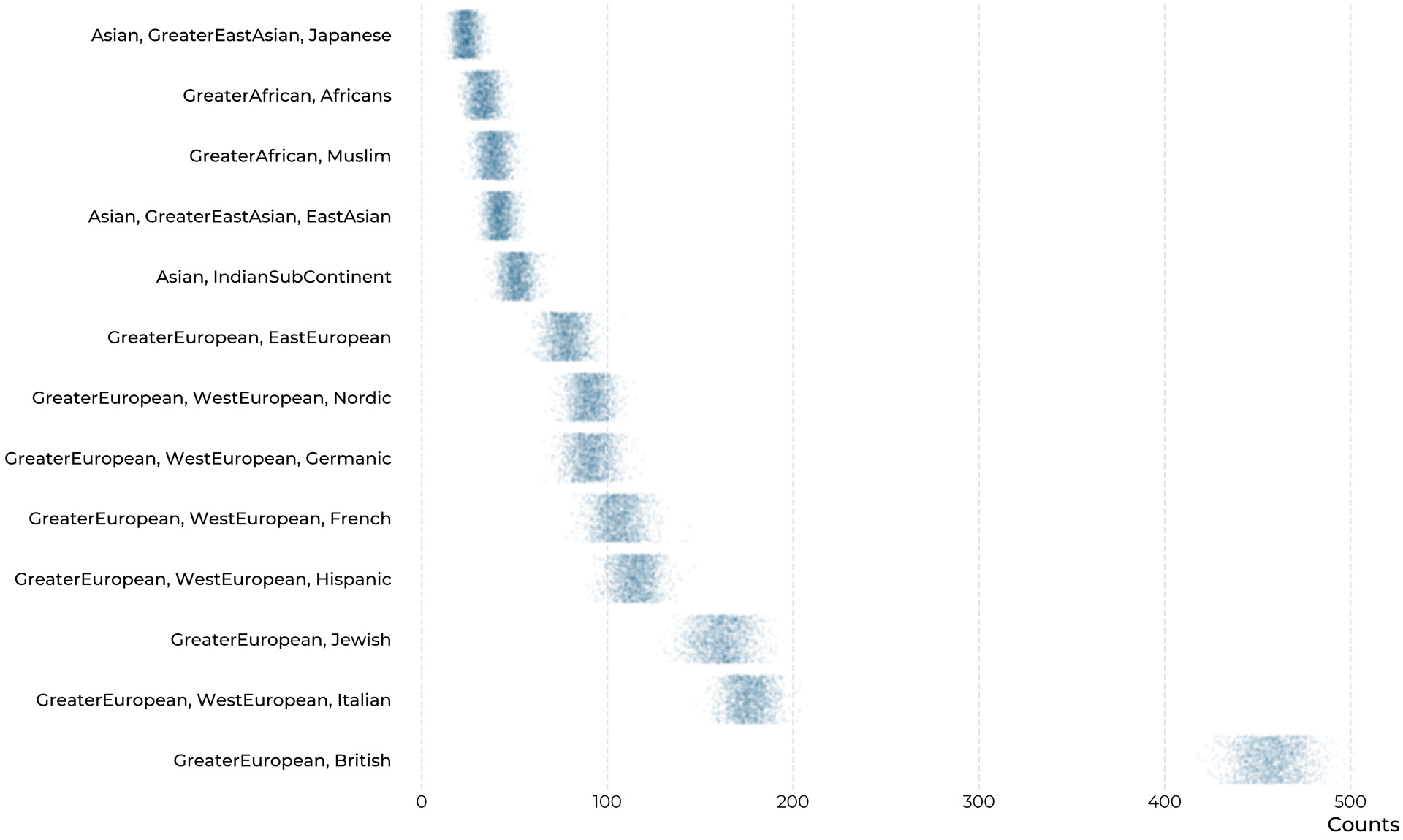

When asking ‘Who studies whom?’, an important part of the answer to ‘Who?’ is the ethnic background of researchers – Arguably it doesn’t only matter, where are the institutions, but also the backgrounds of the people conducting it. But as the ethnic background of a person can and often will be extremely complicated, and very hard to determine from a surface level, we must make clear that the results we present here can be read only as the roughest of estimations. While we hope that they can be of use to spark further discussion, we strongly advise against their inclusion in important decision-making procedures.

To estimate scholars' ethnicities, we turn to the python package 'ethnicolor', which provides a machine-learning model to estimate ethnicities from names, trained on a dataset of name-ethnicity-couplings built from Wikipedia-biographies (Ambekar et al., 2009). The general underlying idea is to represent names as a set of pairs of letters, which of course appear in different frequencies in names from different ethnicities/language-groups, to build a model that correctly predicts ethnicities from names based on the training data, and then to use that model on our novel, unseen data. Because these letter-pair analyses can only grasp from what ethnicity a name is likely to come, the resulting estimates will always be probabilistic. The name 'Jérôme Gonnot' is for example associated by our model with a Western/French heritage with a probability of 0.86, which could maybe also be Hispanic (0.081), but is deemed far less likely to be East Asian, with a probability of only 0.0052.

All ethnicity-estimates we produce are of this probabilistic nature, and in many cases much more uncertain than in the example of Dr. Gonnot. To reflect the inherent uncertainty of this approach, we do not simply assign each person the ethnicity that the model suggests as most probable. Instead, we simulate different scenarios. Over 2000 simulations we randomly draw an ethnicity for each person with the probabilities provided by the model. The results are model-consistent ranges of different scenarios which we visualize below. Each dot represents one simulation. We immediately notice that most of the researchers in our dataset seem of Greater-European/British descent, which includes of course a lot of Northern American names. Other generally European ethnic backgrounds follow suit. Only very little research in the present dataset seems to have been produced by people whose names suggest African or Asian descent.

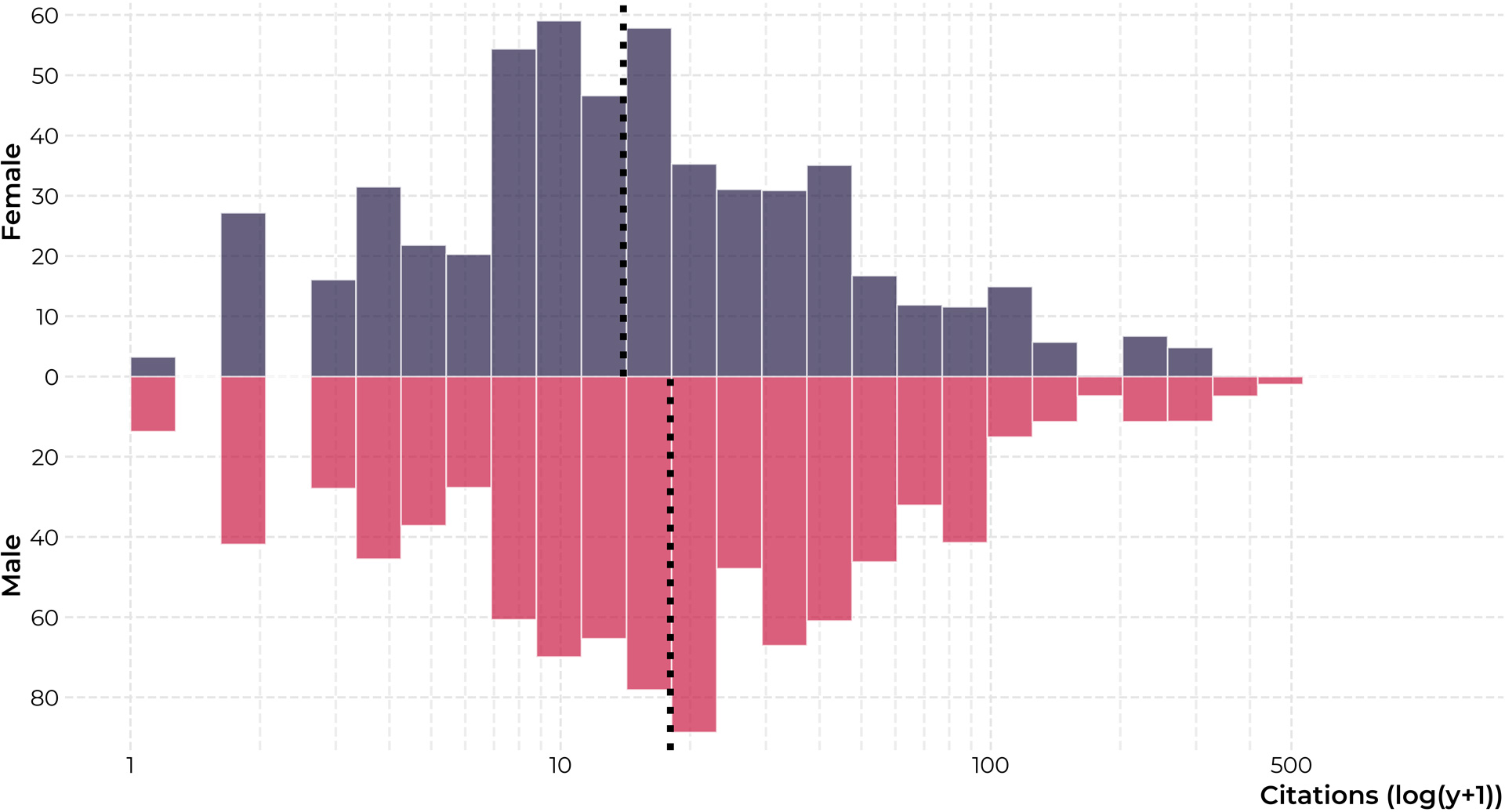

Estimated distributions of author-ethnicity

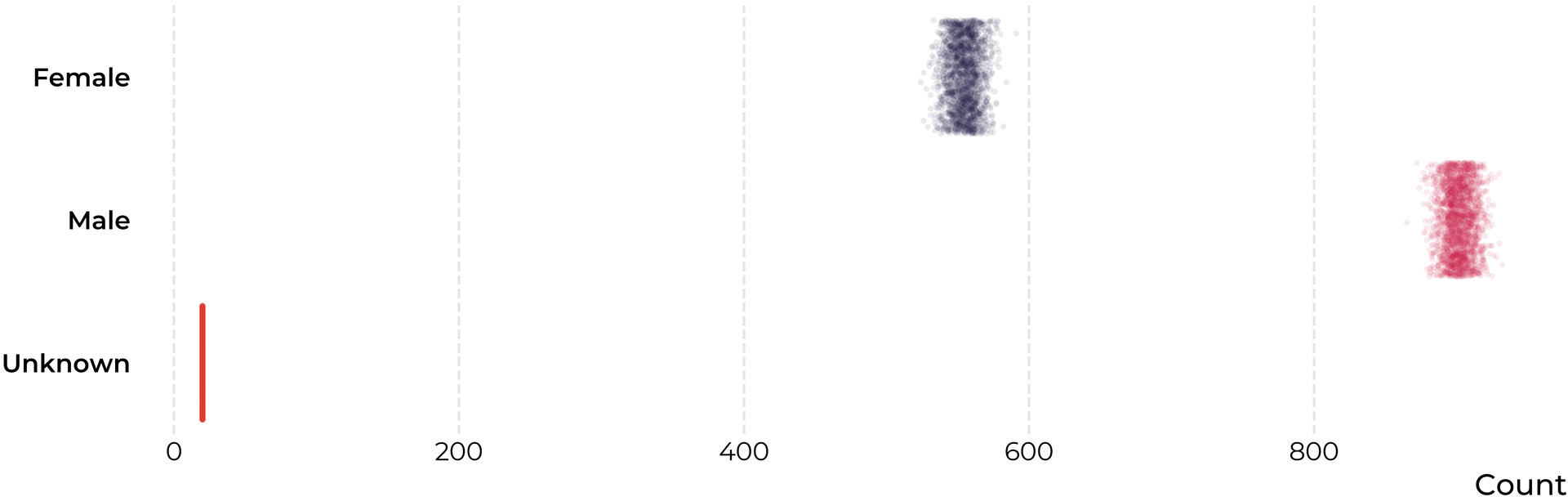

A commonly discussed issue is the distribution of gender among scientists, and so it makes sense to investigate it also in the present sample. As the estimation of ethnicity above, estimating gender, especially in an automated fashion, is an inherently flawed process, which means that, again, our results can only be vague indications. To guess the genders of researchers, we make use of the Genderize-webservice, which returns us for each name in our sample a probability of that person to belong to a specific gender. In most cases, this probability is very close to either zero, or one, as many names are relatively clearly gendered. But some names, e.g. 'Deniz' or 'Andrea', rightly result in more equalized probabilities. To arrive get an idea of the global composition of our sample, we employ the same simulation-based method as above, randomly sampling according to the estimated probabilities, and plotting a range of many possible scenarios accordingly. To acknowledge in our procedure the possibility of mismatches between gender identity and legal name, we further switch the estimated gender with a small probability corresponding to an estimate of the prevalence of trans people, which has the effect of slightly broadening the ranges of our scenarios. The results are shown below.

Estimated distributions of author-genders

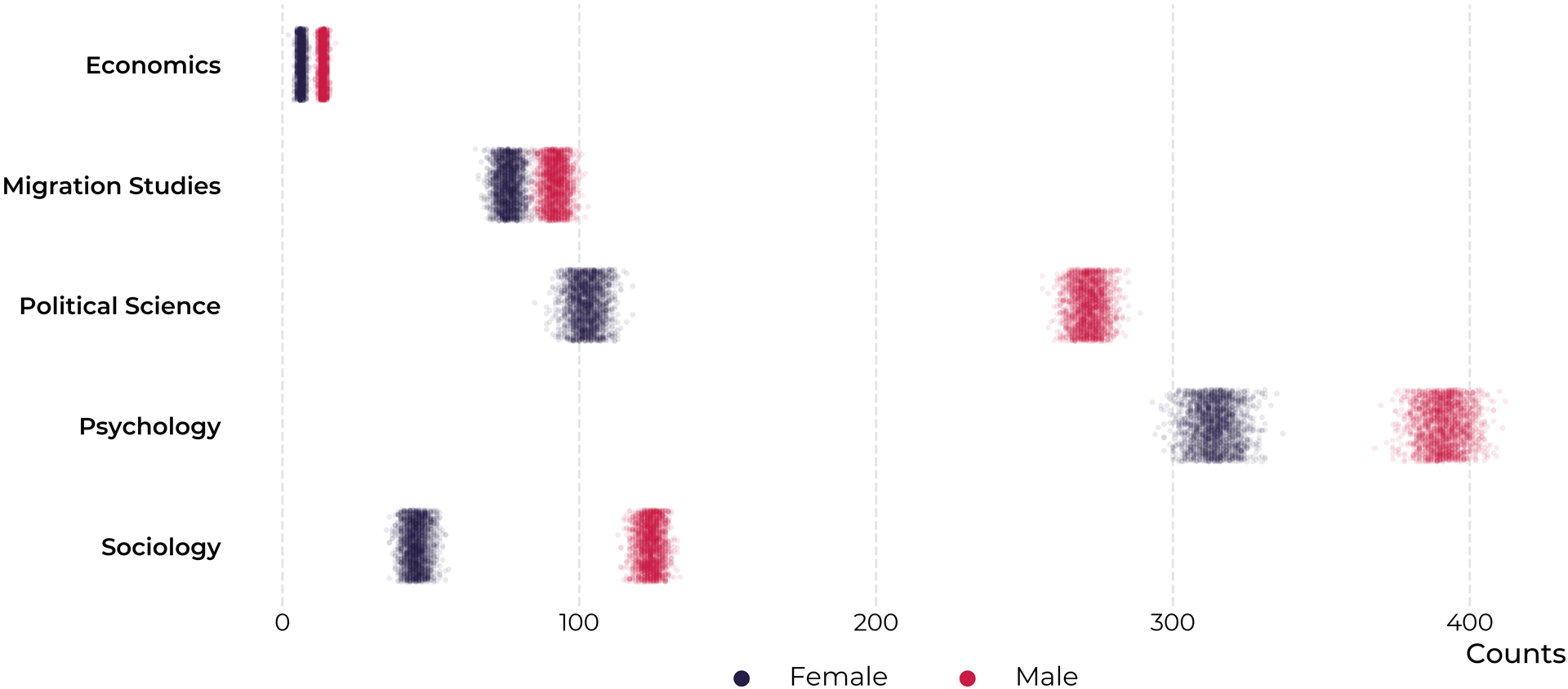

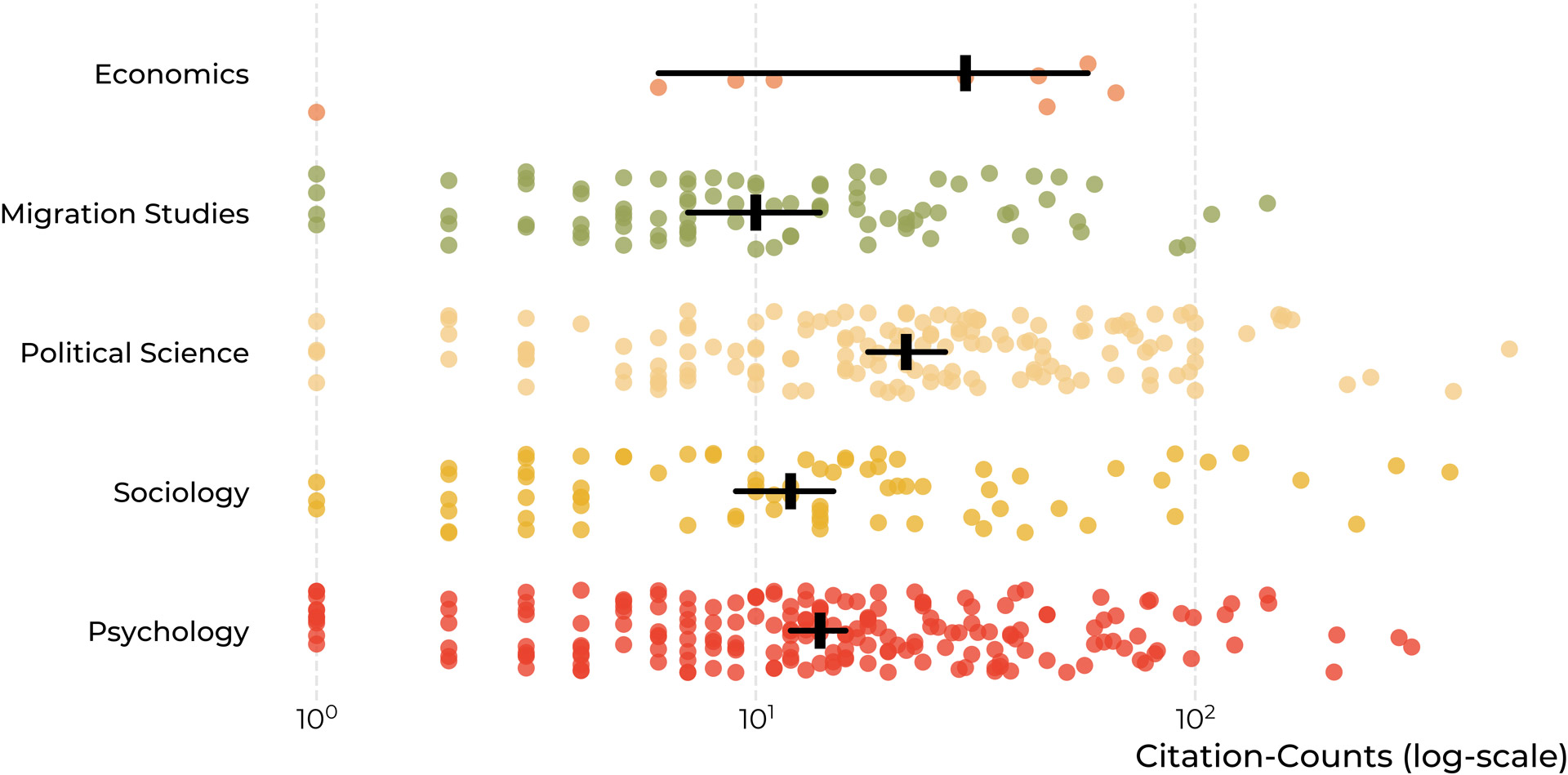

We note that across our whole sample, there were roughly one-third fewer women than men present among the authors. To see whether this effect represents a general feature of the whole dataset, or is more specific, we split these estimates by discipline, as shown in the graphic on the next page. There are stark differences between disciplines. Leaving aside economics, which we suggest to avoid interpreting due to the small proportion it commands in our sample, migration research seems to be the discipline closest to gender parity, while in political science and sociology the difference seems to be the most drastic.

Estimated distributions of author-genders, by discipline

A related interesting question is, whether there are any differences in terms of citations received by men and women in our dataset. Below we have visualized the distributions of received citations to male and female authors, as well as the median values of the distributions. Note that both the distributions and the medians are weighted by the probability of individual researchers belonging to one gender and that the x-axis has been log-transformed. We observe that indeed female researchers receive slightly fewer citations, specifically, four citations less than their male counterparts in the median. As citations can be considered the main currency in a highly competitive field, this seems to be a relevant observation.

Distribution of citations by gender

The explanation for this effect is currently unclear. One possible suggestion is that, as shown in the graphic below, citation rates in political science are much higher than in the other disciplines, which, together with our observation that political science has the most unequal gender distribution, might yield the observed bias. A further likely confounder is, that the amount of articles from different disciplines is not equal over time. Disciplines with comparatively older articles, might for example have had more time to accrue citations. But here further investigation might prove interesting.

Citation distributions between disciplines

Publications

- Re-thinking the drivers of regular and irregular migration: evidence from the Euro-Mediterranean

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Reporto

Year: 2022 - Strategic Communication for Migration Policymakers: Lessons from the State of the Science

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Report

Year: 2022 - Populist Attitudes and Threat Perceptions of Global Transformations and Governance: Experimental Evidence from India and the United Kingdom

Author(s): James Dennison, Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte

Type: Article

Year: 2022 - Sometimes it is the little things : a meta-analysis of individual and contextual determinants of attitudes toward immigration (2009–2019)

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová

Type: Article

Year: 2021 - Migration narratives in the Euro-Mediterranean region: what people believe and why

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Report

Year: 2021 - Narratives: a review of concepts, determinants, effects, and uses in migration research

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Article

Year: 2021 - Thinking Globally about Attitudes to Immigration: Concerns about Social Conflict, Economic Competition and Cultural Threat

Author(s): James Dennison, Andrew Geddes

Type: Article

Year: 2021 - The Role of Human Values in Explaining Support for European Union Membership

Author(s): James Dennison, Daniel Seddig, Eldad Davidov

Type: Article

Year: 2021 - The centre no longer holds: the Lega, Matteo Salvini and the remaking of Italian immigration politics

Author(s): James Dennison, Andrew Geddes

Type: Article

Year: 2021 - How to perform impact assessments: Key steps for assessing communication interventions

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Report

Year: 2020 - Why COVID-19 does not necessarily mean that attitudes towards immigration will become more negative

Author(s): James Dennison, Andrew Geddes

Type: Report

Year: 2020 - What factors determine attitudes to immigration? : a meta-analysis of political science research on immigration attitudes (2009-2019)

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová

Type: Working Paper

Year: 2020 - Explaining voting in the UK's 2016 EU referendum: Values, attitudes to immigration, European identity and political trust

Author(s): James Dennison, Eldad Davidov, Daniel Seddig

Type: Article

Year: 2020 - What policy communication works for migration? Using values to depolarise

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Report

Year: 2020 - Global trends and continental differences in attitudes to immigration : thinking outside the Western box

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová, Jérôme Gonnot, Claudia Brunori

Type: Policy Brief

Year: 2020 - Attitudes to immigration in the Arab-speaking world: Explaining an overlooked anomaly. UN International Organisation for Migration: Migration Research Series

Author(s): James Dennison, Mohamed Nasr

Type: Report

Year: 2020 - A basic human values approach to migration policy communication

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Article

Year: 2020 - Impact of Public Attitudes to migration on the political environment in the Euro-Mediterranean Region: Southern Partner Countries

Author(s): James Dennison, Mohamed Nasr

Type: Report

Year: 2020 - What are Europeans’ views on migrant integration? : an in-depth analysis of 2017 Special Eurobarometer

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová, Thomas Liebig, Silvia Migali, Marco Scipioni, Gilles Spielvogel

Type: Working Paper

Year: 2020 - Explaining the emergence of the radical right in Spain and Portugal : salience, stigma and supply

Author(s): James Dennison, Mariana S. Mendes

Type: Article

Year: 2020 - Public attitudes to migrant workers : a (lasting) impact of Covid-19?

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová

Type: Commentary

Year: 2020 - How niche parties react to losing their niche : the cases of the Brexit Party, the Green Party and Change UK

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Article

Year: 2020 - A proposal for simultaneous reform of the House of Commons and House of Lords

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Article

Year: 2020 - The dynamics of electoral politics after the Arab Spring : evidence from Tunisia

Author(s): James Dennison, Jonas Bergan Draege

Type: Article

Year: 2020 - Cast in the same mould : how politics during the impressionable years shapes attitudes towards immigration in later life

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová, Anne-Marie Jeannet

Type: Working Paper

Year: 2019 - Impact of Public Attitudes to migration on the political environment in the Euro-Mediterranean Region

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Report

Year: 2019 - The Austrian parliamentary elections 2019 : are Austrians anti-immigrant?

Author(s): Lenka Dražanová

Type: Policy Brief

Year: 2019 - Public opinion on migration

Author(s): James Dennison

Type: Policy paper

Year: 2019 - Public attitudes on migration : rethinking how people perceive migration : an analysis of existing opinion polls in the Euro-Mediterranean region

Author(s): James Dennison, Lenka Dražanová

Type: Research Report

Year: 2019 - A rising tide? : the salience of immigration and the rise of anti-immigration political parties in Western Europe

Author(s): James Dennison, Andrew Geddes

Type: Journal Article

Year: 2018 - Brexit and the Perils of Europeanised Migration

Author(s): James Dennison, Andrew Geddes

Type: Journal Article

Year: 2018 - Op-ed: Are Europeans turning against asylum seekers and refugees?

Author(s): James Dennison, Andrew Geddes

Type: Op-ed

Year: 2017 - Public attitudes to immigration in Germany in the aftermath of the migration crisis

Author(s): Teresa Talò

Type: Policy Brief

Year: 2017 - Explaining attitudes to immigration in France

Author(s): James Dennison, Teresa Talò

Type: Working Paper

Year: 2017

Other outputs

Non-Academic Publications

- Contributor to: IOM (2018) Informing the Implementation of the Global Compact for Migration

- Dennison, J. and Dražanová, L. (2018) Attitudes to Immigration in Europe and the Southern Mediterranean

- Contributor to: CEPS (2018) The Cost of Non-Europe in Migration Policy

- Dražanová, Lenka. 2018. Eurobarometro, speciale immigrazione: in che modo le opinioni degli italiani differiscono da quelle dei cittadini europei? Questione Giustizia.

Invited Speakers

James Dennison

- ‘Attitudes to immigration and the future of the European Union’, Club of Venice, Venice, 2018

- ‘The political effects of attitudes to immigration’, MIDEM conference, Berlin, 2018

- ‘Brexit: Why the UK and why now?’, University of Amsterdam, 2018

- ‘Explaining Attitudes to Immigration in Europe’, European Parliament, Brussels, 2018

- ‘Attitudes to Immigration in Europe and the Southern Mediterranean’, Tunis, Tunisia, 2018

- ‘What would a fair Brexit look like?’, EUI Thoughts on the future of Europe series, 2018

- State of the Union 2018, EUI Florence, Narratives and Attitudes to Migration. See video here.

- ‘Understanding attitudes to immigration in Italy today’, 2018, Metropolis conference. See video here.

- Presenting evidence to the European Parliament Select Committees. See video here.

- ‘What Europeans think of immigration’ at EPIM, Brussels, 2018

- ‘Looking behind the culture of fear’ Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Budapest, 2018

- ‘Public Attitudes on Migration’, European Commission talk with cabinet, Brussels, 2017

- ‘The Rise of Populism’, After dinner speaker with Barclays and McKinsey, London, 2017

- ‘International cooperation in responsibility-sharing for refugees’, American University in Cairo, 2017

Lenka Drazanova

- University of Vienna lecture, March 2021. “A leopard can’t change its spots: How and why early life experiences affect our attitudes to migration?” What video (in English) here.

- Czexpats in Science conference. Key note lecture: “Původy postojů k migraci (Origins of attitudes to migration)” December 2020. Watch video (in Czech) here.

- MPC Webinar Covid-19 and Border Restrictions in the EU: Is Schengen in Crisis?, December 2020. Contribution: “Border restrictions in the EU: what does the public think?” Watch video (in English) here.

- ReSOMA Webinar on public opinion towards migration. March 2020. Watch video (in English) here.

- ‘Effectively communicating on migration’ ReSOMA Transnational Thematic Feedback Meeting, Brussels, 2019.

- MPC Webinar ‘Migration, Citizenship and Public Perceptions’, November 2019. Contribution: “Blame it on My Youth: The Origins of Attitudes Towards Immigration“.

- ‘Affective and Cultural Dimensions of Integration of Immigrants and Refugees’ Workshop, Berlin, 2019. German Institute for Economic Research (DIW).

- ‘The Italian Decree on Security and Immigration: how Legitimate and Effective is it?’ , Florence, 2019. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

- ‘EU Migration Challenges: What Can Diplomacy and Science Together Contribute?’ European Academy of Diplomacy, Cracow, 2019.

- Prague Process Senior Officials’ meeting. International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD), Prague, 2018.

- ‘Perceptions of Migration in Europe. Implications for Policy-Making’. Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), Brussels, 2018. Watch video (in English).

- ‘Migrazioni e asilo nella regione euro-mediterranea’. Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Pisa, 2018. Watch video (in Italian).

More than one OPAM member at the same event

- MPC Webinar Immigrants’ Political Attitudes. Assimilation or Divergence? January 2022. Contribution: “Migrants attitudes towards immigration – convergence towards natives? Evidence from Europe” (with Michaela Sedovic) What video (in English) here.

- MPC Webinar Public attitudes towards immigration and immigrants, May 2021. Contribution: “What factors affect attitudes to immigration?” What video (in English) here.

- ‘Navigating between social science research and policy making recommendations’. Florence, 2019. Migration Policy Centre Annual Conference.

- ‘Europe’s turning point on migration? Politics, Policy and Predictions ahead of the 2019 Elections’, Brussels, 2019. Watch video (in English) here.

Blog Posts and Press

James Dennison

- On-going blogging at https://medium.com/@jamesdennison_7425

- The emergence of the populist radical right in Spain demonstrates the conditions under which such parties succeed, LSE Europp

- Why immigration has the potential to upend the Italian election, LSE Europp

- Op-ed: Are Europeans turning against asylum seekers and refugees?, European Council on Refugees and Exiles

Lenka Drazanova

- Are older people more hostile towards immigrants? MPC Blog – Debate Migration, September 2021.

- Public attitudes to migrant workers: a (lasting) impact of Covid-19? MigResHub commentary, November 2020.

- The long-term closure of schools due to COVID-19: Are we set for a less tolerant future? MPC Blog – Debate Migration, June 2020.

- Austria’s snap election: Is the Freedom Party (FPÖ) going to fade away? EUIdeas corporate blog of the European University Institute, October 2019.

- Austria’s snap election: Why has the far-right Freedom Party suffered such heavy losses? University of Oslo, Center for Research on Extremism “Right Now!” blog, September 2019.

- Measuring Changes in Ethnic Diversity Over Time: The Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF) MPC Blog – Debate Migration, September 2019.

- Eurobarometro, speciale immigrazione: in che modo le opinioni degli italiani differiscono da quelle dei cittadini europei? Questione Giustizia, December 2018.

- Dražanová, Lenka. The Special Eurobarometer on Integration of immigrants in the European Union: How do Italians differ in their views compared to the rest of Europe? MPC Blog – Debate Migration, March 2018.

- Immigration and the Czech presidential election. LSE Europp