-

-

Andrew Geddes

Full-time Professor

Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

Director

Migration Policy Centre

Read more

Blog, Rights, protection and inclusion

The Future of Counter-Smuggling

Introduction At least 37 migrant men died following a collective effort to “crash” the fence separating Morocco from Melilla, one of the two Spanish enclaves in North Africa, on June 24th. The number of...

A new study carried out at the Migration Policy Centre shows strong support for people displaced by the war in Ukraine and that governments need to show that they have a plan to manage mass displacement otherwise attitudes could change.

More than 5 million people have now been displaced by the war in Ukraine. Many have moved to neighbouring states and face uncertain futures. An important element of this uncertainty as well as a powerful influence on policy is how citizens in key hosting states have responded. To understand more about this, we surveyed people in eight countries: Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. A combined total of 8525 respondents were interviewed by the survey company Respondi in the eight countries between 25th May and June 6th 2022 with nationally representative samples of approximately 1000 respondents in each country.

We found strong support in all eight countries for welcoming Ukrainian refugees. Strikingly, this support for Ukrainian refugees contrasts with a much cooler attitude to other refugee groups. While there is general satisfaction with governmental responses, we detected potential fragility linked to people’s desire to see that the situation is managed.

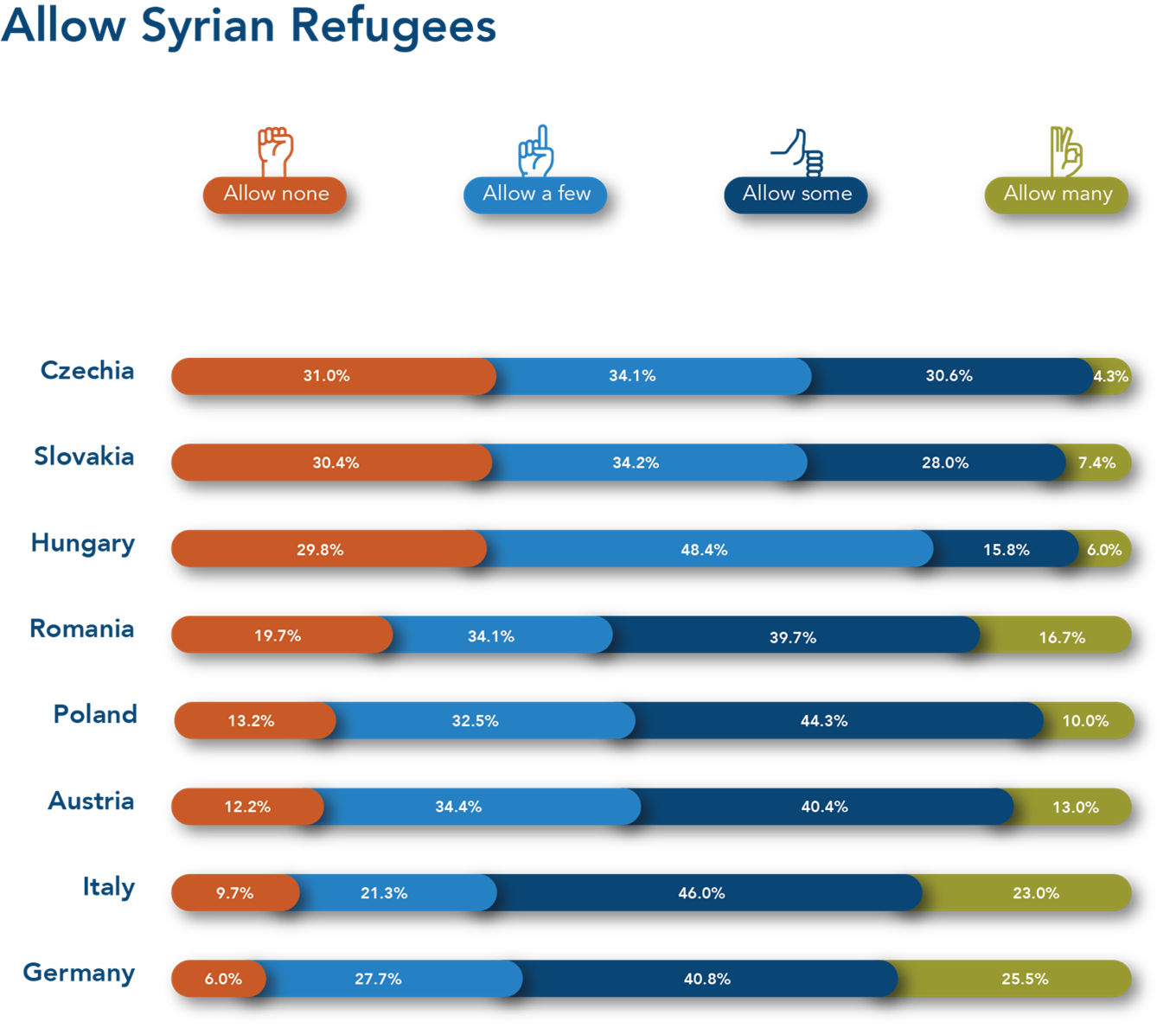

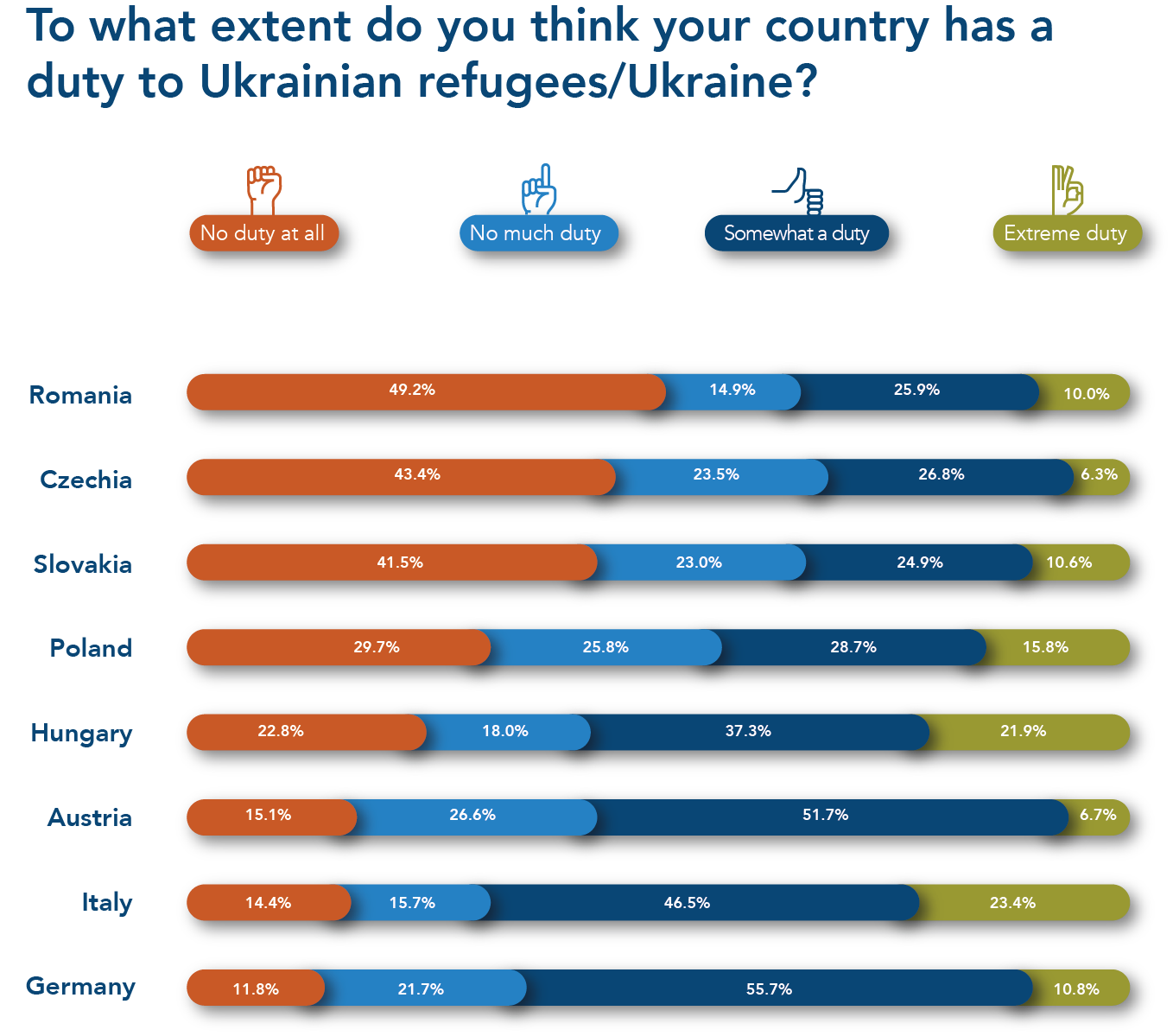

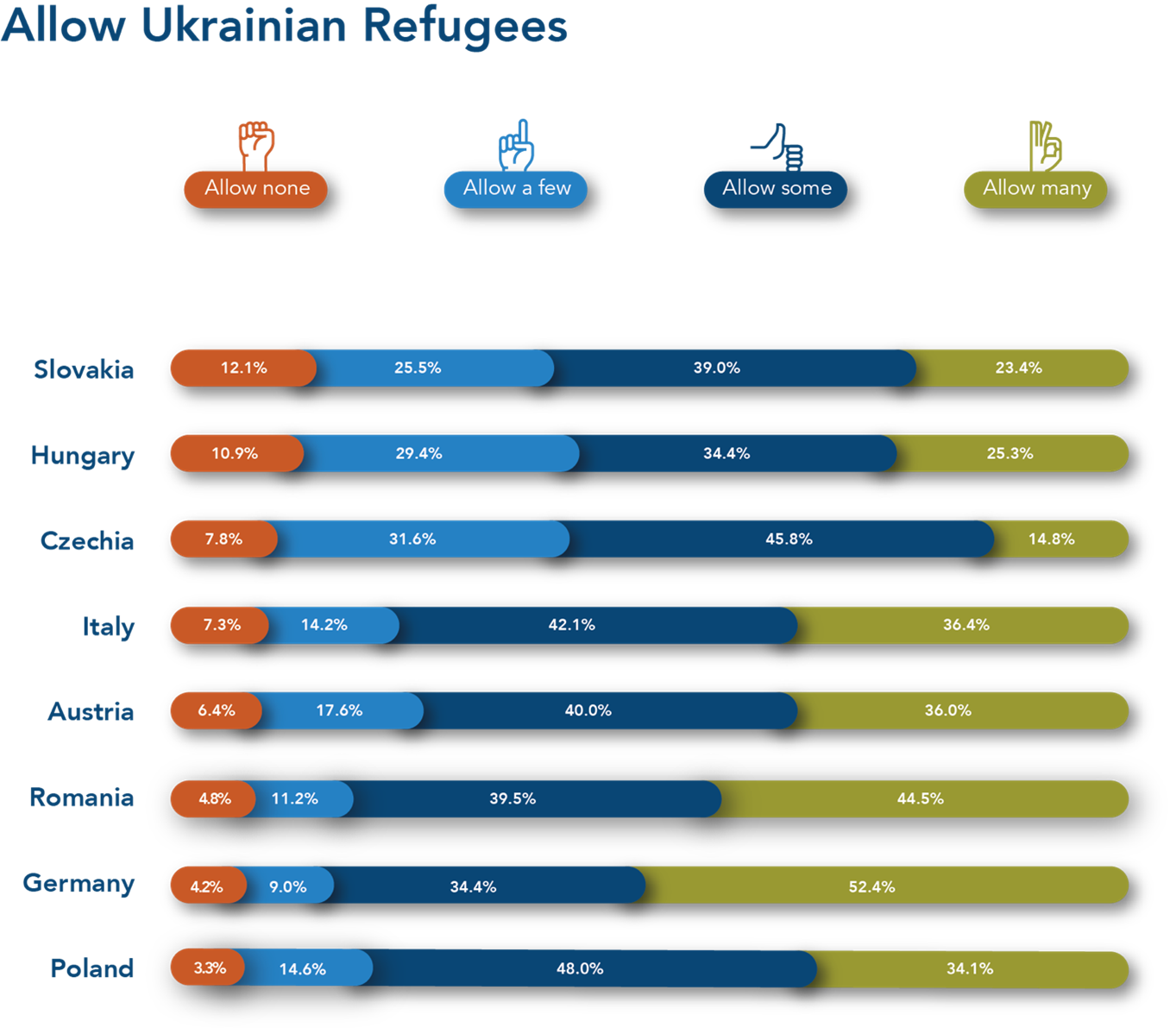

Drilling down into the details, we asked respondents whether their country should allow refugees to come and live in their country. To see if there were differences in attitudes to Ukrainian refugees compared to refugees from other countries, we randomly split our sample into two parts. Half of the respondents were asked about Ukrainian refugees, while the other half were asked about Syrian refugees. We found strong support for Ukrainian refugees. Even in Hungary and Slovakia, which were the most negative countries, hard-line respondents – meaning those who would allow no Ukrainian refugees – amounted to only around 10 per cent. Germany and Romania were strikingly positive: more than half of the respondents in these two countries would support allowing many Ukrainian refugees to come to their country.

Crucially, the debate is not a simple binary between those who oppose entry for refugees from Ukraine and those who favour their free entry. True, there is strong support for Ukrainian refugees, but with a preference that numbers be regulated or controlled.

When we contrasted attitudes to refugees from Ukraine with those from Syria we found a stark difference, most notably in the Visegrad group of countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia). In Germany, Italy and Austria attitudes to Syrian refugees are also more negative when compared to Ukrainians, albeit the difference is not as pronounced as in the Visegrad countries.

When we contrasted attitudes to refugees from Ukraine with those from Syria we found a stark difference, most notably in the Visegrad group of countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia). In Germany, Italy and Austria attitudes to Syrian refugees are also more negative when compared to Ukrainians, albeit the difference is not as pronounced as in the Visegrad countries.

After Germany and Italy, respondents in Romania were the most welcoming to displaced Syrians. Immigration is a low salience issue in Romania, which could help explain these relatively welcoming attitudes compared to other countries in Central Europe where there is strong governmental hostility to non-European migrants and refugees. This is in line with the Visegrad countries’ governments’ strong opposition to EU plans to relocate asylum applicants from Syria back in 215.

Levels of satisfaction with government responses are crucial. We asked specifically about refugees from Ukraine, although it can be difficult to disentangle this specific issue from more general levels of satisfaction with governments. Importantly, in 2015, at the height of Syrian displacement, it was the failure of governments to respond effectively that was integral to the crisis. A crisis of displacement soon morphed into a political and institutional crisis with a breakdown of European cooperation. We found that a majority of respondents to our survey were satisfied – at least, so far – with their governments’ actions towards Ukrainian refugees. Only Slovakia and the Czech Republic had satisfaction levels below the average.

Levels of satisfaction with government responses are crucial. We asked specifically about refugees from Ukraine, although it can be difficult to disentangle this specific issue from more general levels of satisfaction with governments. Importantly, in 2015, at the height of Syrian displacement, it was the failure of governments to respond effectively that was integral to the crisis. A crisis of displacement soon morphed into a political and institutional crisis with a breakdown of European cooperation. We found that a majority of respondents to our survey were satisfied – at least, so far – with their governments’ actions towards Ukrainian refugees. Only Slovakia and the Czech Republic had satisfaction levels below the average.

As a note of warning, our results suggest that the levels of satisfaction are far from overwhelming with potential fragility. Looking more closely, we found that those respondents who are satisfied with their government’s actions are also much more likely to be supportive of their country hosting refugees from Ukraine. The direction of causality is difficult to disentangle, but the key point is that if support fades then levels of satisfaction in government would also be likely to fall.

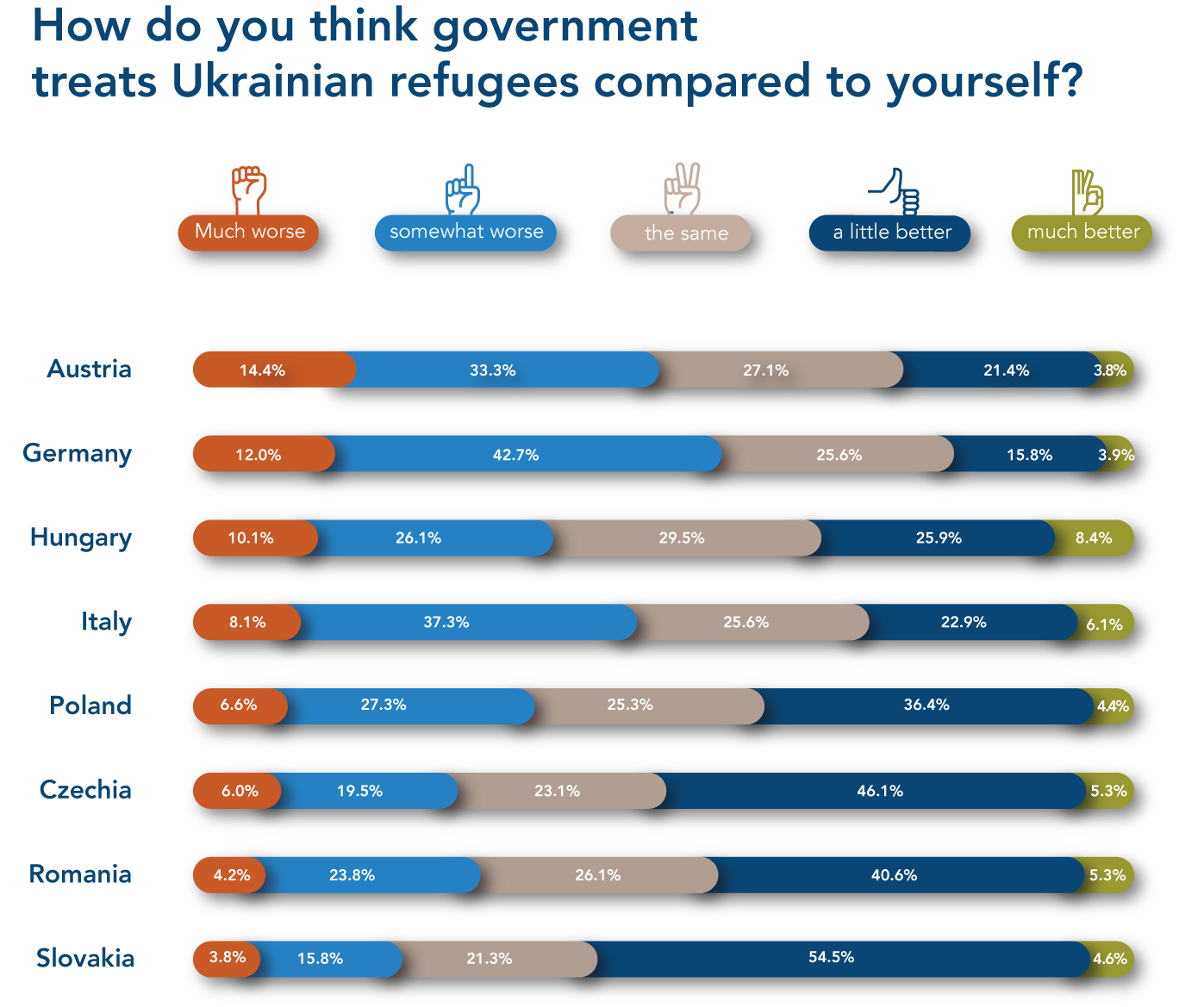

Another key issue for long-term integration and social cohesion is how Ukrainian refugees are (factually and in perception) treated compared to the nationals. To explore this, we asked respondents in the eight countries surveyed whether they thought that their government treats Ukrainian refugees better or worse compared to them. More than half of German respondents think that their government treats Ukrainian refugees worse than themselves while, in contrast, more than half of Slovakian respondents think that their government treats Ukrainian refugees better than themselves. Again, while causality can be difficult to disentangle, responses to migration are powerfully driven by perceptions of fairness. Irrespective of whether or not refugees objectively do receive better or worse treatment, subjective perceptions of fairness and unfairness can have very powerful effects on attitudes towards refugees.

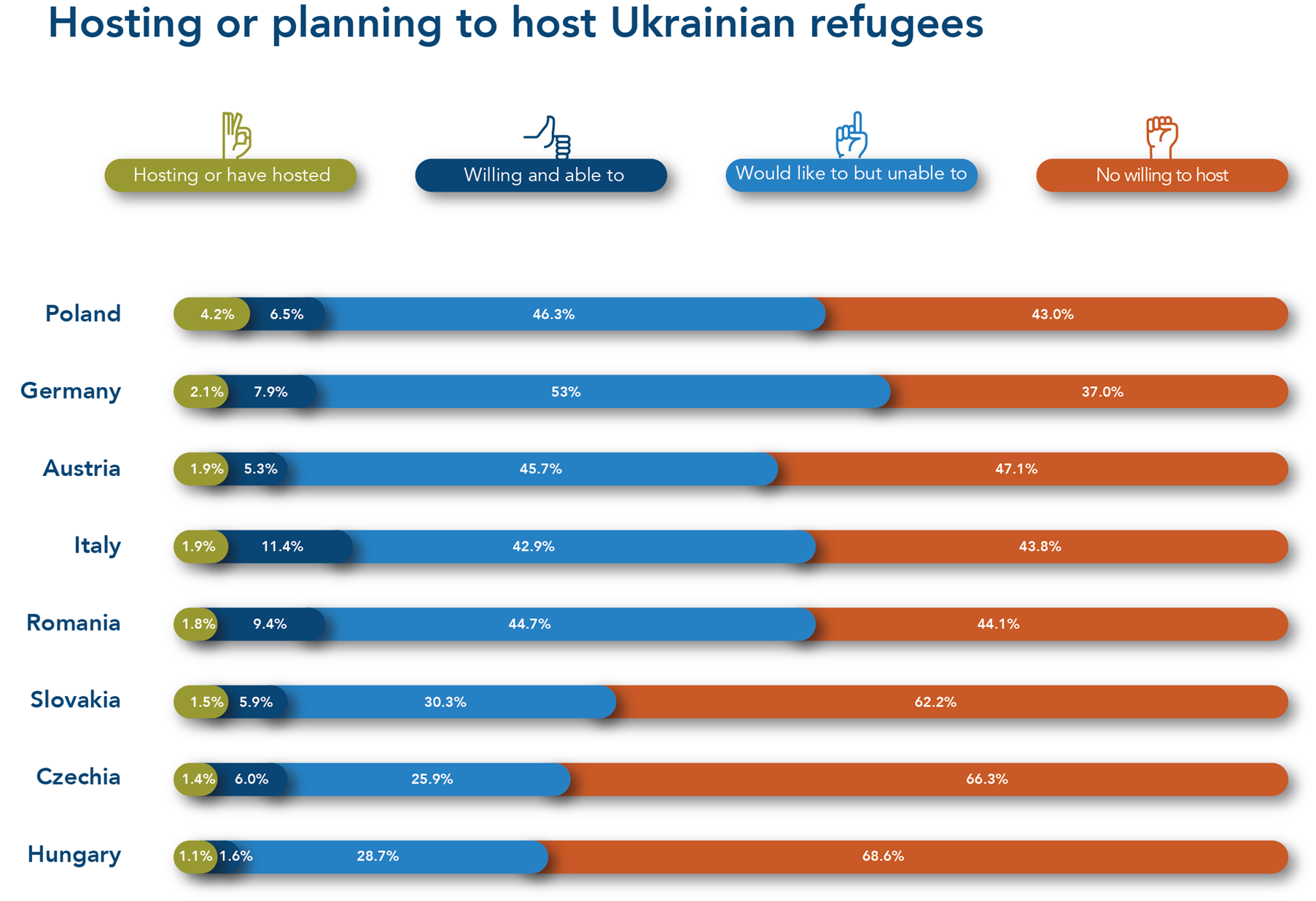

One final aspect of the response to Ukrainian refugees concerns the extraordinary mobilisation by private citizens, particularly in Poland but in other European countries too. When we asked about attitudes to hosting we found that clear majorities of citizens in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are not willing to host Ukrainian refugees. In all other countries, the majority has either hosted (albeit a very small number), would be willing to host or would at least like to but are unable to. The small proportion of people in each country who have either hosted or are willing and able to host suggests a necessity for governmental responses to address the current situation with incoming Ukrainian refugees, rather than relying on private initiatives by citizens.

Good policy responses to displacement from Ukraine also require an informed understanding of citizens’ attitudes. There is a strong wave of support for Ukrainian refugees that exceeds that for other refugee groups. There is also general satisfaction so far with government responses, but we also detected an underlying fragility linked to peoples’ need to see that the situation is properly managed otherwise the risk is that a crisis of displacement can turn into a political and institutional crisis. If the conflict persists and mass displacement becomes a long-term issue, people will want to know that there is a plan and that it is being implemented.