Read more

Blog, Rights, protection and inclusion

The Honduran Caravan: how did things get here, and what lies ahead?

By the time this blog entry is online, the largest contingent of what has been called the Honduran migrant caravan will be approaching Mexico City, having covered mostly on foot over 1.000 kilometers from...

Drawing from new research on migration in the Middle East, this blog post shows how migration-related interdependence does not simply allow ostensibly more powerful states – in this case Egypt – to push their policy agenda onto supposedly weaker states, such as neighbouring Jordan and Libya. Interdependence, in fact, can allow the ‘weak’ to coerce the ‘strong’ into significant concessions because of the latter’s vulnerability to the negative effects of migration-related interdependence, such as closing off routes for labour migrants from the ostensibly more powerful country.

The steady rise in cross-border mobility internationally has placed migration firmly on the global agenda. The debate on how to involve states in the management of migration is far from over – in fact, one key assumption is that strong states are needed for migration governance to function: a group of powerful states, the argument goes, would be able to develop a strategy towards migration governance in which they would be able to involve weaker states, and ultimately, lead to an institutionalised process. The expectation would be that states would understand the long-term benefits of cooperation and put faith in multilateral processes that could then lead to refugee and migration regimes. In this sense, liberalism considers migration governance as being akin to other areas of world politics – from trade or development to food security or climate change – in which states should be working together for the common good. For liberal international relations theory, an opportunity to reduce conflict and create lasting peace appears once states rely on each other and develop interdependence. Yet, why has this yet to occur in the area of migration? Why does migration appear to engender more polarisation, confusion, and discord in world politics than cooperation?

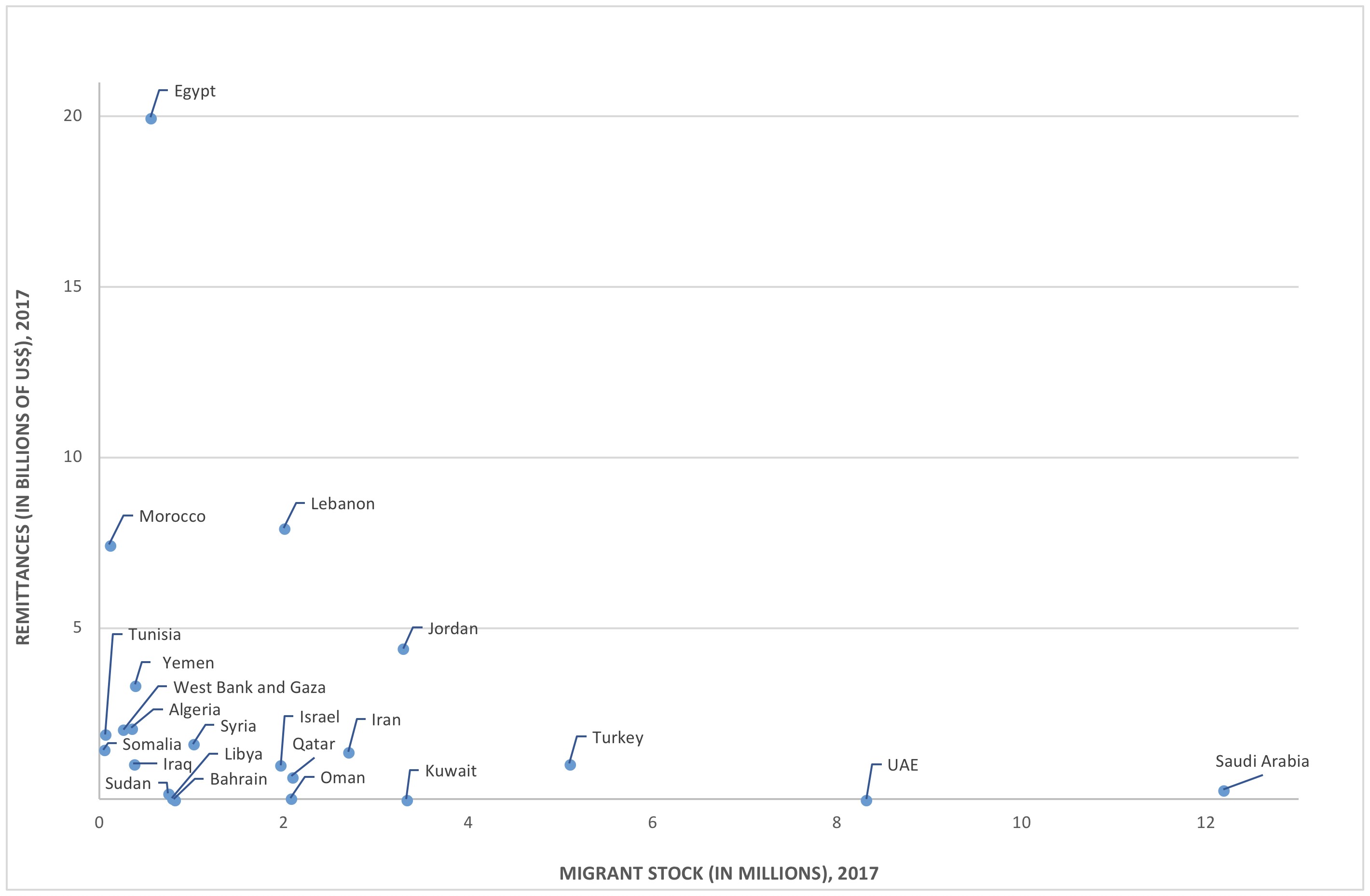

In a recently-published article, I investigate the political importance of migration interdependence, which I define as the reciprocal political economy effects created by cross-border mobility in both sending and host states, in the Middle East. The Middle East – comprised of 22 Arab states plus Israel, Iran, and Turkey – is one of the most complex migration sub-systems. It features both major migrant sending states (Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, Yemen), as well as important migrant host states (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait). The Middle East has historically enjoyed sizeable intra-region migration flows – most recently linked to the post-1973 migration to oil-producing states of Libya and the Gulf Cooperation Council. Migration interdependence continues to be high across the region (see Figure 1). Why, then, do we see little evidence of regional migration governance – or, indeed, of states’ wish towards such coordination?

Figure 1: Migration Interdependence in the Middle East

My findings indicate that migration interdependence does not always allow more powerful states to push their policy agenda on weaker ones; in fact, the very existence of interdependence gives weaker states the opportunity to coerce stronger ones into submission. I focus my analysis on Egypt in the aftermath of the 2011 ‘Arab Spring’ events; beyond being one of the largest countries of the region, Egypt wields considerable power in the Arab world, both politically and militarily, has a long tradition of labour emigration, and is a long-standing ally of the United States in the Middle East. Yet, Egypt was coerced by two considerably-weaker neighbouring states – Libya and Jordan – into shifting two sets of policies: Jordan forced the Egyptian government to increase its exports of natural gas to the Kingdom, while Libya forced it to extradite a number of Gaddafi-era elites. The two new policies were clearly against Egypt’s national interests, and the policy shifts occurred only after the two weaker states started deporting Egyptian migrants. What explains this?

The focus on labour migration in the Middle East demonstrates how weaker states are able to manipulate migration interdependence according to their interests. Libya and Jordan had understood that, in the aftermath of the ‘Arab Spring,’ Egypt was particularly susceptible, or vulnerable, to migration interdependence. It relied on a steady outflow of emigrants in order to continue reducing its high unemployment figures and increase the inflow of economic remittances. In this context, the presence of migrants within their borders was a potent ‘weapon of the weak’ that less powerful states – the small Kingdom of Jordan and even war-torn Libya – were able to use to their advantage. The manipulation of migration interdependence in the Middle East contribute to conflictual relations – against the expectations of theorists expecting cross-border mobility to lead to interstate cooperation.

Do my arguments travel beyond the two cases discussed here? Labour migration typically features as an element of statecraft and power politics across the Global South: Afghan authorities have not hesitated to manipulate migration interdependence in their bilateral relations with Pakistan since mid-2016. In an effort to force Pakistan to reverse its decision to unilaterally close the Chaman border crossing, weaker Afghanistan recently adopted a law that requires passports, rather than mere identity cards, and frequently deports Pakistani labour migrants. In response, in March 2017, Pakistan relented as its prime minister decided to open the crossing as “a gesture of goodwill.” Bilateral disputes between Egypt and Sudan, including the contested border of the Halayeb Triangle, led Khartoum to bar entry to Egyptian men aged between sixteen and fifty without visas in 2017 – as part of an ongoing bilateral conflict.

In sum, these observations are part of a theoretical analysis that underlines the contribution of interdependence to debates on migration governance across two dimensions. First, the rise of migration flows across the world is reshaping traditional understandings of the balance of power, as weaker states are now able to extract key concessions from stronger states, both economic and political. In that sense, it is imperative that the needs of smaller states, particularly in the Global South, are taken into account in any attempt toward sustainable migration governance. Second, it is likely that migration interdependence may exacerbate conflictual relations rather than lead to interstate accord. A more complete analysis of the interplay between cross-border mobility and world politics will, ultimately, allow us to understand what types of international institutions and cooperation are required to meet the challenges of global migration.

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.

—-

For more insights by Gerasimos Tsourapas on the politics of migration interdependence have a look at the book The Dynamics of Regional Migration Governance (Edward Elgar, forthcoming) edited by the MIGPROSP research team.