Read more

Blog, Migration Governance

EU-Africa Summit: A Eurocentric Approach

2-3 April 2014, 80 European and African Heads of State and Government and leaders met in Brussels for the fourth EU-Africa Summit. Although the Summit had originally been planned to focus on security and...

Italian scholars have increasingly discussed whether and how the ongoing economic recession has affected the employment of migrant workforce (Bonifazi & Marini 2013; Pastore, Salis & Villosio 2013; Reyneri, 2010). Most of the questions concern home-care for elderly people, which is, traditionally, an important source of employment for foreign women (Picchi 2012; Semenza 2012; Qualificare 2013). The assumption has been that, due to the impoverishment of their households, Italian women from working-class backgrounds have overcome their reluctance to take up jobs in this sector, thus entering into competition with foreign women.

This post argues that what is happening in the current Italian economic crisis replicates tendencies already observed in the crises of the past century that challenge the predominant argument of “women as a reserve army”. Scholars have, indeed, shown how already during the Great Depression (Milkman, 1976) until the most recent 1997 Asian financial crisis (Lim, 2000), women labour participation did not follow the expectation of those who saw the female workforce as being welcomed in times of expansion, but rejected in economic contractions. On the contrary, the women labour participation rate has increased without any kind of job competition with men since men and women are normally hired following different patterns. This post enlarges the perspective of the risk of a male-female competition to a competition between foreign and Italian women, in times of crisis.

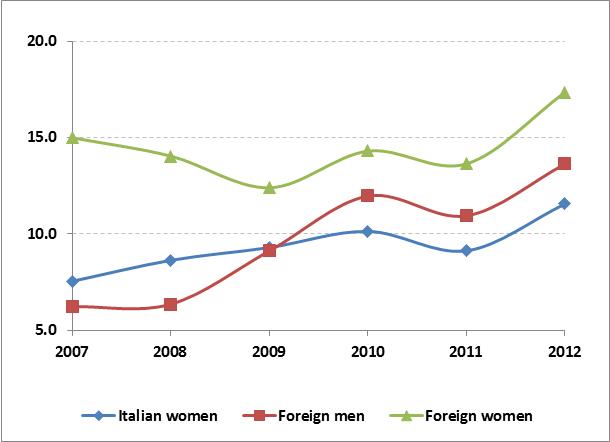

Following the on-going global economic recession, the situation and role of foreign women in the Italian labour market seems to have changed. While unemployment rates of foreign men and Italian women had been immediately negatively affected by the recession, those of foreign women show an almost flat trend, which has only increased since 2011 (figure 1).

Figure 1 – Unemployment rate by sex and nationality, Italy, 2007-2012

Source: Authors’ elaboration on Labour Force survey data

This can be explained by the fact that foreign men and Italian women were disproportionately hit by the recession: the recession, after all, mostly affected the sectors of construction and manufacturing (where men are typically employed) and those of financial services and trade (where native women are overrepresented, on average). On the contrary, sectors such as care and domestic work – where foreign women are found in large numbers – were relatively less affected thanks to the persistent demands of transnational migrants in the Italian family-based welfare (Näre 2013).

However, more recently Italian women, especially former housewives, have also entered the labour force in order to counterbalance the loss of jobs of the men in their households. Home-based care and domestic work are one of the options open to them. Does it mean that they are entering into competition with foreign women for this sort of jobs?

We do not think so. In 2011, only 1 out of 10 Italian working women were employed in low skilled jobs, whilst 7 out of 10 foreign women were employed there. Regarding the home-care sector, Italian statistics (INPS) show that, while the number of Italian domestic workers only slightly increased in the 2000s, (from 128,000 in 2003 to 163,000 in 2011), that of foreign women almost doubled (from around 345,000 in 2003 to more than 600,000 in 2011). In addition, the ‘profiles’ of Italian and foreign nationals within the domestic work sector largely differ.

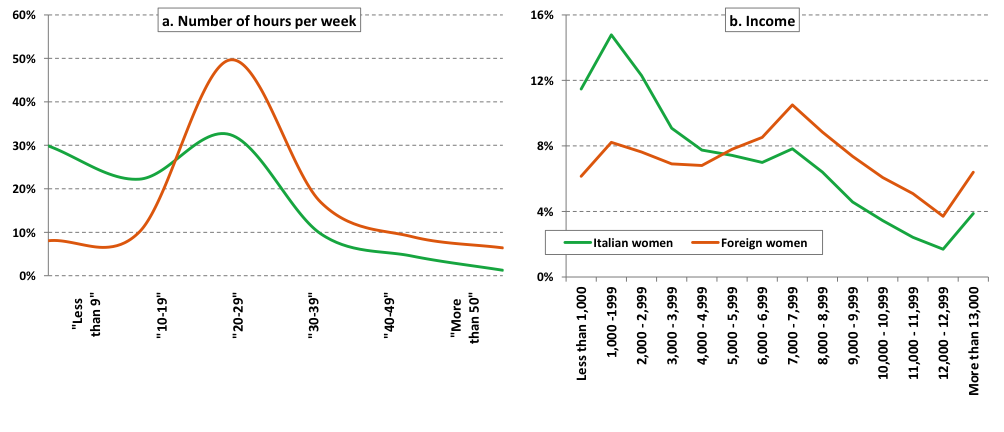

Figure 2 – Italian and foreign women employed in the domestic sector by number of hours per week and income level, 2011

Source: Authors’ elaboration on INPS data

For instance, Italian women work typically fewer hours per week than foreign women: 9 out of 10 Italians work fewer than 29 hours per week, while 8 out of 10 foreign women work more than 20 hours per week (figure 2a). Domestics’ earnings are consequently very different between the two populations: 7 out of 10 Italian nationals earn less than 7,000 euros per year while 5 out of 10 foreign nationals earn more than 7,000 euros (figure 2b). This shows that, for Italian women, jobs in the domestic sector are still seen as “extras” to compensate the fall off of male salaries in their households. On the contrary, for foreign women these same jobs represent their main source of income, which leads them to work longer hours. This usually entails the cohabitation with their care-receiver, in line with the growing need of around the clock home-care service for elderly people. Italian women are still reluctant to work under these sorts of conditions.

Since the employment of migrant women workers is intrinsically characterised by their availability for higher intensity and less remunerated jobs, the profile of Italian and foreign women workers seldom overlaps. Thus, for the purposes of nationality-based comparison between foreign nationals and Italians in the domestic sector, labour market complementarity dynamics are observed: the fear of “stealing jobs” has no grounds as the specific labour profiles remain distinct.

Anna Di Bartolomeo, Research Fellow at the MPC, RSCAS, EUI

Sabrina Marchetti, Jean Monnet Fellow at the Global Governance Programme, RSCAS, EUI

—

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.

References

Bonifazi C, Marini C (2013). The impact of the economic crisis on foreigners in the Italian labour market. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40(3): 1-19.

Pastore F, Salis E, and Villosio C (2013). L’Italia e l’immigrazione low cost: fine di un ciclo? Mondi Migranti 1: 151-172.

Reyneri E (2010) L’impatto della crisi sull’inserimento degli immigrati nel mercato del lavoro dell’Italia e degli altri paesi dell’Europa meridionale. PRISMA Economia-Società-Lavoro 2(2): 1/17.

Picchi S (2012) Le badanti invisibili anche alla crisi?. Available online at: http://ingenere.it/articoli/le-badanti-invisibili-anche-alla-crisi

Semenza R (2012). Le conseguenze della crisi sull’occupazione femminile. il Mulino 61(5): 842-848.

Milkman R (1976) Women’s work and economic crisis: some lessons of the great depression. Review of Radical Political Economics 8(1): 73-97.

Lim JY (2000) The effects of the East Asian crisis on the employment of women and men: the Philippine case. World Development 28 (7): 1285-1306.

Näre L (2013) The ethics of transnational market familism: inequalities and hierarchies in the Italian elderly care. Ethics and Social Welfare 7(2): 184-197.