Read more

Blog, Public Attitudes

Governments’ Information Campaigns for Potential Migrants: What’s the Point?

Debates about governmental information campaigns targeted at migrants raises crucial and underexplored questions that have huge implications for migration governance: who monitors the content and quality of such messages? How can quality assurance incorporate...

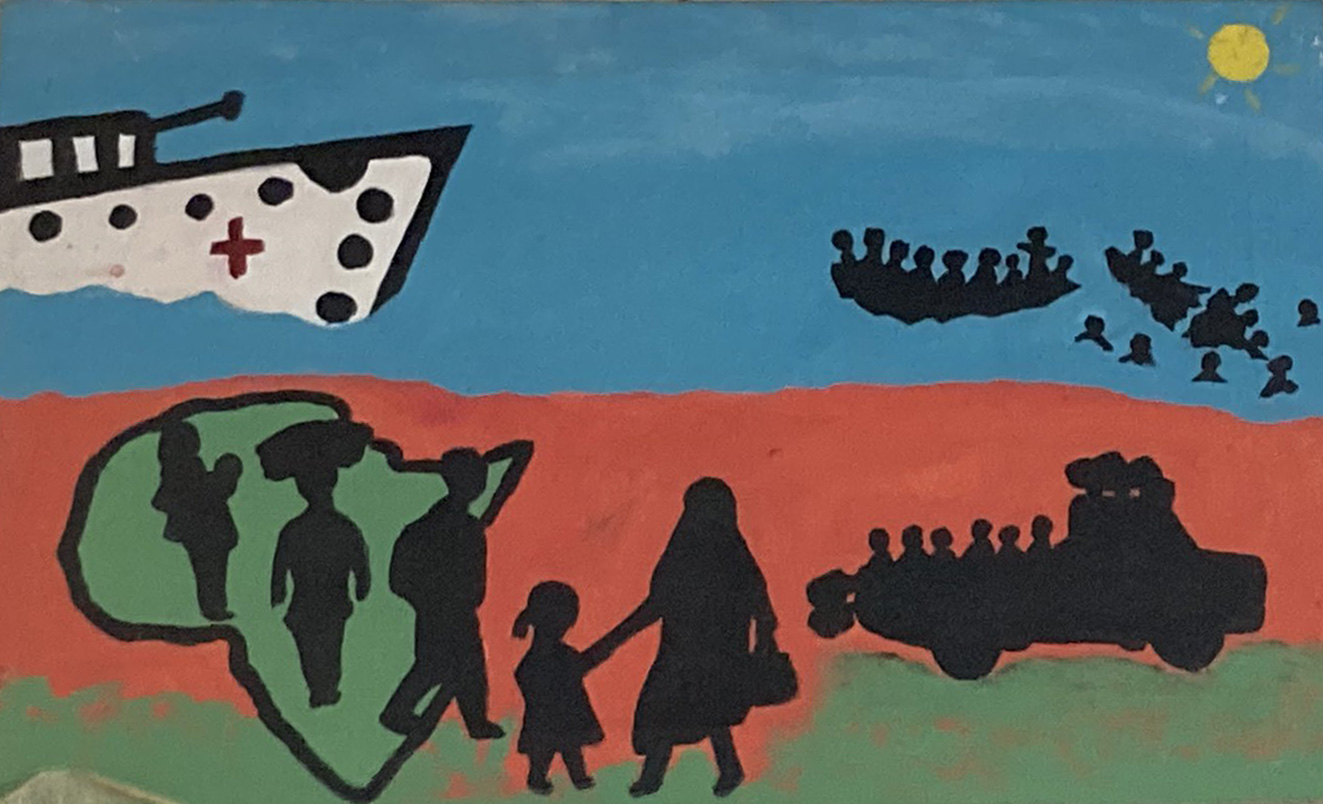

The EU is trying to discourage Africans from travelling irregularly to Europe, but can they be persuaded to stay in African countries? This blog post shows how an EU-funded narrative is perceived by West African youth in The Gambia. We specify the key components of the messages that are conveyed and also explain why they do not cut through to Gambian youth.

“We suffered a lot because the way Libyans treat us is too hard. Myself, I’ve been in jail for 8 months. I am in prison without no reason”.

This brief excerpt from the video testimony of a man called Moro describes his failed attempt to migrate to Europe. The video aims to make Africans more aware of the dangers of traveling through the Sahara and Libya. There are many similar videos circulating on social media – and it does not stop there: theatres, film projections as well as returned migrants who recount their experiences are part of these information campaigns to discourage emigration. Typically financed by the EU or individual member states, it is often the International Organization for Migration (IOM) that implements on the ground.

As part of the BRIDGES research project we traveled to different regions in The Gambia to find out how young Gambians perceive these information campaigns and how they think and collect information on migration. With just over two million inhabitants, The Gambia is the smallest country in West Africa, but it has the highest percentage of emigrants compared to the overall population. Between 2014 and 2018, around 35,000 young Gambians attempted to cross the Mediterranean to Europe irregularly. The country is considered democratic since the Gambians managed to oust a dictator in 2016. As a result, very few who now arrive in the EU receive asylum status. In Germany, almost 6,000 Gambians are required to leave the country.

Information campaigns assume that a potential migrant has a distorted – or at least an incomplete – picture of the journey to and life in Europe. If only this potential migrant knew how dangerous the journey or how difficult life in Europe were, then he or she probably wouldn’t come at all. But is this assumption correct? Does more information and knowledge make people stay at home?

The campaigns do seem to have a considerable reach. We found that in villages in the Gambian hinterland, people know the stories of the videos and the migrants who have returned or died on the way. There seems to be no lack of information on the dangerous journeys, received via the campaigns or word-of-mouth. But the information – more precisely, the narratives – compete with one another. Gambians traditionally see migration as something positive: a migrant would gain experience, display courage and improve the lives of his/her family and community. The EU, in turn, wants to convey three very different messages: first, life in Europe is not as good as you imagine; second, the journey to Europe is dangerous; and thirdly, there are opportunities in your home country.

“No matter how hard life is in Europe, it cannot be compared to here”. Bakary expresses what many in The Gambia think. Certainly, migrants in Europe have to work hard. But they can progress. Young people often referred to the few Gambians who have become famous in Europe such as Ebrima Darboe, a Gambian who made the perilous journey across the Mediterranean Sea at age 14 and now plays for star coach José Mourinho at the Italian football club AS Roma. Such role models are contrasted with one’s own life in The Gambia. Others highlighted that it is easy to observe that the lives of families whose children migrated have (materially) improved. In The Gambia, few young people manage to get stable employment and have to get by with occasional jobs and little more. Without their own means and real income, marriage is out of reach. Even people with official employment are often only slightly better off. In Gambia, police officers or teachers earn most often only between EUR 40 and 100 per month. Remittances from migrants in Europe – even if they are only comparatively small sums – can make a real difference in terms of having enough to eat. As a result, Gambians who have made it to Europe receive respect, and some parents may motivate their children to do the same. Moreover, migrants who do not make it to Europe are often blamed on an individualized basis. This person would not have worked enough, that’s why his or her life is so miserable – “I can do it better”.

The second message from the EU, on the dangerous journey, is the most resonant. Most Gambians are aware of the dangers and risks of the journey. Probably even more important than official videos are the stories of friends or acquaintances that circulate in villages. Most interviewees knew someone who was captured in Libya or even died on the journey. Families or whole communities have to join forces to pay ransoms demanded by kidnappers in Libya. Women are at even greater risk than men. As stories of sexual violence on the journey circulate, many returned women are unable to find a man whose family agrees to marriage. Religiosity is often an answer to cope with the fear of the journey. A person’s destiny would be predetermined; the journey will unfold as it is meant to be.

Most young Gambians agree with the third message displayed in the campaigns, which concerns domestic opportunities for training or jobs. Many have heard of the courses portrayed in the campaigns or even attended them. Others, however, say that rural youth lack access to most of these trainings. We were often told that one can be trained but still not find a job; or start a business, but not have customers able to buy products. Such training does not structurally change the labor market. Many referred to jobs in the fishing sector as a case in point: European and, to an even greater extent, Chinese fishing boats would cast their huge nets off the Gambian coast and export the fish to Europe and China. Gambian fishermen with their smaller boats struggle to compete and increasingly lose income.

So how effective are these information campaigns financed by the EU? Information is part of an individual decision-making process. The amount, type, and quality of information can affect a person. Parents of young Gambians who considered migrating pointed out that they became more aware of the dangers of the journey after watching pertinent videos. As a result, they discouraged their children from attempting the migratory journey. But these cases are the exception. Other factors play a more important role in the decision process as to whether a young Gambian leaves: the lack of prospects to improve one’s professional or private situation; the everyday struggle to get by financially; the societal respect given to migrants who made it to Europe; and a religious belief that one’s life is predetermined. Arafang, a young Gambian, sums it up: “It’s not the information that counts, it’s our situation”.

The authors are members of the Brussels Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Migration and Minorities (BIRMM), Vrije Universiteit Brussel. The research has been conducted in the context of the H2020-Project ‘BRIDGES – Assessing the Production and Impact of Migration Narratives’.