Read more

Blog, Public Attitudes

The long-term closure of schools due to COVID-19: Are we set for a less tolerant future?

While much of the existing discussion of the effects of school closures due to COVID-19 has been focused on impacts on educational outcomes, student performance and future earnings, this blog explores a different type...

COVID-19 has revealed pre-existing fault-lines in the recruitment, employment and living conditions of Nepali migrant workers abroad. Now faced with their unprecedented return to Nepal, the challenges of repatriation and reintegration are immense while the future of emigration remains uncertain.

Nepali migrant workers: Essential and vulnerable

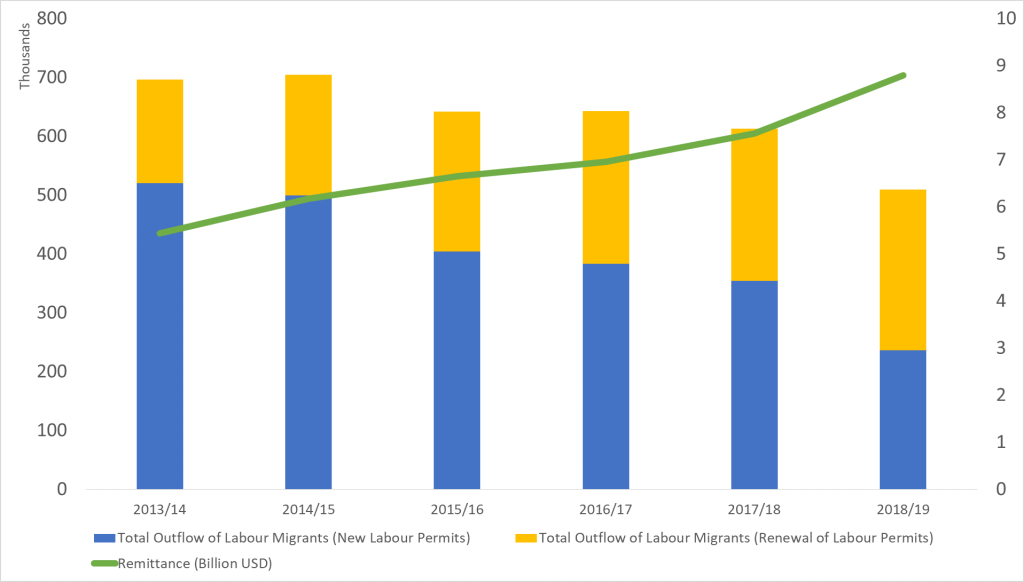

With a remittance-to-GDP ratio of over 25 per cent, labour migration is crucial to Nepal’s economy (see Figure 1 below). Nepali workers primarily head to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Malaysia, on temporary contracts in occupations typically considered “low-skilled”. It is these very occupational categories—in sectors like cleaning, security, storekeeping, and domestic work—that are now being recognized as “essential” during the pandemic for keeping societies functioning amid the lockdowns.

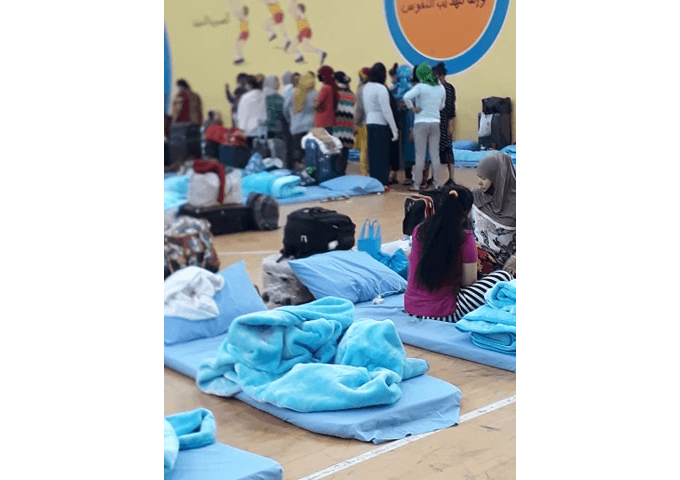

In a stark contrast to their indispensable role, COVID-19 has also brought into light the reality of many migrant workers’ vulnerabilities. Living in squalid labour camps with shared sub-standard toilets and crowded canteen facilities, physical distancing is impossible. Consequently, migrant labour camps have emerged as hotbeds for the spread. Significant sections of labour camps in Qatar’s Industrial Area that housed at least 2000 Nepali workers or three apartment buildings with 9000 migrant workers in Kuala Lumpur are examples of housing areas that had to be sealed to blunt the outbreak. The Non-Resident Nepalis Association (NRNA) estimates that over 14500 Nepalis abroad have tested positive, with over 10,000 in the GCC countries and Malaysia.

Figure 1: Annual Outmigration (Left) and Incoming Remittances (USD Billion) (Right) from Nepal

Source: Remittance (Nepal Rastra Bank) and Migration Flows (Dep. of Foreign Employment)

Covid19 and Nepali labour migration: Making well-known problems worse

In many ways, the pandemic has revealed pre-existing fault-lines in the recruitment, employment and living conditions of workers abroad. There is nothing new about vulnerabilities faced by undocumented migrant workers, the public health risks of living in unhygienic conditions or about the inadequate worker protection regulations for migrants in the lower rungs of the ladder. Many migrants including in hospitality, retail, and construction have lost their jobs or are being asked to take unpaid, partially paid or if lucky, paid leaves. For workers who paid recruitment costs equivalent to several months’ wages to intermediaries to obtain these opportunities, such job losses and unplanned returns can have lasting consequences. A report by Oxford Economics predicts that employment in the GCC countries could fall by 13 per cent, with job losses of 900,000 in the UAE and 1.7 million in Saudi Arabia. With economic slowdown due to plummeting oil prices, disruptions in international mobility and supply chains, the cancelation or delays in large scale development projects or events, thousands of migrant workers have been left in a lurch.

Going home ?

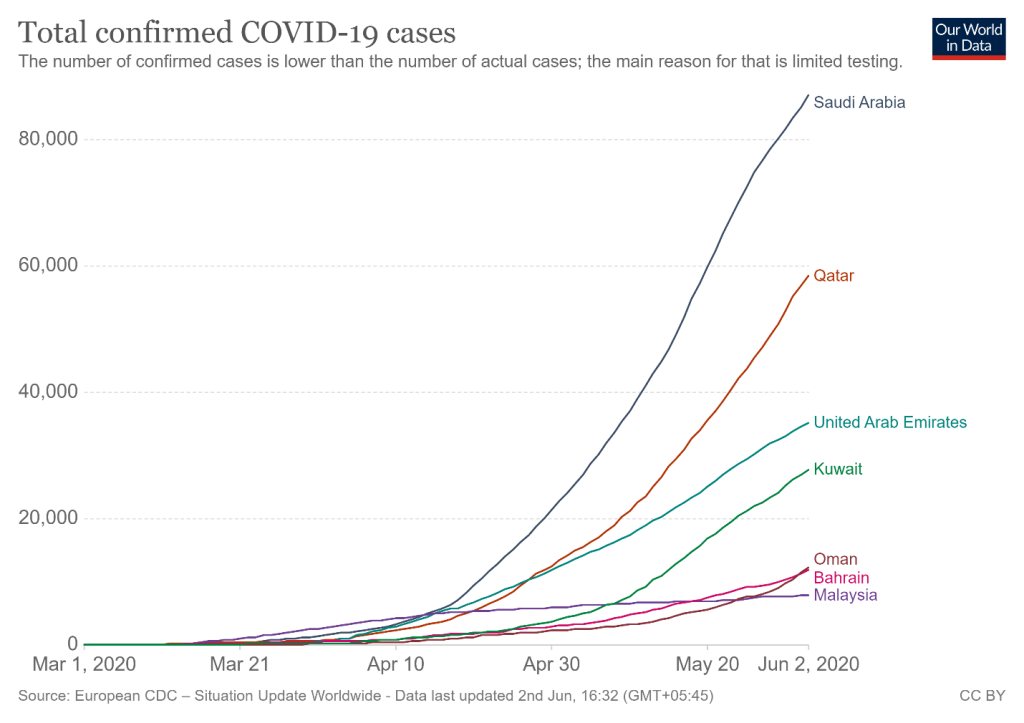

Whether it is the rising number of COVID-19 cases (see Figure 2 below) and the fear of exposure given their living and working conditions, job insecurity or difficulties in affording food and accommodation, there is an increasing demand from Nepali migrants to be brought home. The Nepal Government is also facing pressure from Governments of destination countries to take back its citizens. Kuwait, for example, has provided an amnesty to undocumented workers that sponsors their tickets back home and waives their overstay fines. 3500 undocumented Nepali who availed of the amnesty have been living at the Government’s quarantine facilities, waiting for flights to resume. In Malaysia, while many migrant workers are working overtime in glove factories making life-saving PPEs to meet the rising global demand, undocumented workers outside are being rounded up and taken to overcrowded and unhygienic detention centers, even in the midst of a pandemic, increasing the pressure to be repatriated urgently. There are also countries like Romania, Poland and Maldives, where Nepali migrant workers have been displaced, albeit in a smaller scale, who require support.

Figure 2: Total Confirmed Cases in the GCC Countries and Malaysia

Challenges for the Nepal Government: Repatriation and reintegration

From June 5th, the Government has begun the repatriation of Nepalis stranded abroad. 25,000 Nepalis will be brought back in the first phase, with vulnerable groups including pregnant women, undocumented workers, those on short-term visas and those with job losses or expired contracts in the initial priority list. The Government’s initial estimates show that around 130,000 migrants will be returning, although it is subject to error because of unreliable data. These figures exclude migrant workers in India who are unrecorded given the open border between the two countries. Tens of thousands of Nepali workers stranded across the border, who have been transported from various parts of India on the Government of India’s “Shramik trains” for migrant workers, have been entering Nepal recently. Their repatriation management has been delegated to local governments who are completely inundated given inadequate testing and quarantine facilities.

With only one international airport in Nepal, the repatriation flights will have to be staggered over months. In Nepal’s history, the largest repatriation effort was from Libya in 2011 when 1700 migrant workers were brought home after the onset of the war. But unlike repatriations of the past, this exercise is challenging not just because of the volume, the diverse destination countries where they are located and the spread of origin hometowns within Nepal where they will need to be transported, but also because of the health risks throughout the process that requires meticulous planning and monitoring. It is crucial to ensure that migrants test negative prior to departure and are quarantined and tested in Nepal upon arrival. There is also a fear of stigma against returnees and their families from local communities given that many of the cases of COVID-19 so far have been imported.

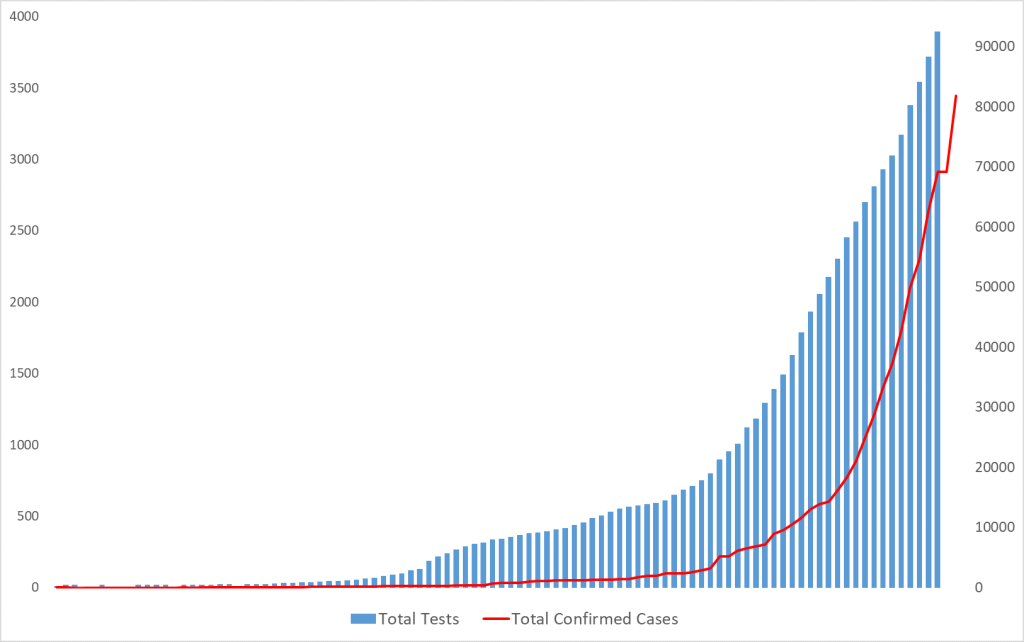

Nepal itself is grappling with a beleaguered health system domestically. While the imposition of lockdowns was timely in Nepal, the recent surge in the number of cases to 3762 across 71 out of 77 districts once testing has been ramped up has overwhelmed the country’s health system. To accommodate thousands of new arrivals daily poses significant challenges, and without marshaling significant resources to ensure adequate testing and quarantine, there are risks of conflagration. There is also a fear of stigma against returnees in local communities given that many COVID-19 cases so far have been imported. The repatriation experiences of other migrant origin countries reveal that these challenges are very real. There are cases of Pakistanis returning from the UAE and Indians and Sri Lankans returning from Kuwait testing positive upon arrival despite undergoing tests before departure. The Philippines’ quarantine facilities were quickly overwhelmed after which they had to halt repatriations temporarily to decongest quarantine facilities and change course to ramp up PCR testing and limit daily arrivals to 400. When local governments units (LGUs) were initially reluctant to let in returning overseas workers, the central Government had to issue a memo requiring LGUs to take back workers who furnished evidence of negative Covid-19 tests.

Figure 3: Total Confirmed Cases (Right) and Tests (Left) in Nepal

Source: Our World in Data

In addition to repatriation, the Nepal Government also faces a monumental challenge of ensuring those who return en masse are properly rehabilitated in the domestic economy. The World Bank estimates a 14 per cent drop in remittances to Nepal, which can be consequential given its role in poverty reduction – studies reveal that a fifth of the poverty reduction between 1995 and 2004 in Nepal could be attributed to remittances. Even before the pandemic, Nepal’s migration outflow has been declining since 2014/15 and it has been long recognized that reliance on a handful of destination countries makes workers vulnerable to macroeconomic and geopolitical shocks in the region. This was seen in the 2014 fall of oil prices, in the Qatar-Gulf fall out and the recent geopolitical instability in the region. Similarly, the Gulf’s nationalization policies that prioritize recruitment of locals and Nepal’s emigration ban on specific sectors like domestic workers or on specific countries like Malaysia in 2018, have contributed to the decline.

Nepali labour migration after Covid19: An uncertain future

Strategies to address the shrinking demand for Nepali workers in the traditional destination countries have been twofold —diversification towards new destination countries and domestic employment creation—but both are on shaky grounds now. Shocks brought by COVID-19 are distinct as no country has been spared. Countries in Europe and East Asia that have become increasingly important for Nepali migrants given demographic shifts and worker shortages are ravaged by the virus. Sectors important for domestic employment generation in Nepal such as tourism and services have been adversely impacted, and studies show a grim picture: a 75 per cent drop in the hours for wage employment among Nepalis in western Nepal and job losses among 3 in 5 employees. But given that migrants including Nepalis are occupying jobs that nationals are unwilling to take up, demand in certain sectors will be sustained through the pandemic or bounce back once economies start recovering, so the extent of the impact on migration flows remains uncertain. With the economies of Nepal, current and potential destination countries simultaneously impacted, there is much uncertainty about the future that awaits Nepali migrant workers.

Upasana Khadka formerly advised the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security, Nepal and is a Columnist for the Nepali Times.

Upasana is an alumna of the MPC’s Migration Summer School 2019.

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.