Read more

Blog, Migration Governance

MIGPROSP PhD researchers’ thoughts ahead of The Dynamics of Regional Migration Governance conference

By Laura Foley and Andrea Pettrachin As the two newest recruits to the MIGPROSP project, this is our first conference as part of the team and we are really looking forward to it. The...

The best-interest-of-the-child principle is the cornerstone of several legal and policy instruments adopted by EU Member States both at the national and the EU level. However, when it comes to unaccompanied minor asylum seekers in Europe, EU Member States shirk the obligations that they signed up to in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The poor implementation of existing laws and policies in the asylum field, the lack of cooperation and the reluctance of Member States to accept responsibility, share burdens and show solidarity is compounded by a culture of disbelief and suspicion towards child migrants. The result is a double exclusion, for these minors, as, in addition to being alone, unaccompanied children also find themselves unprotected.

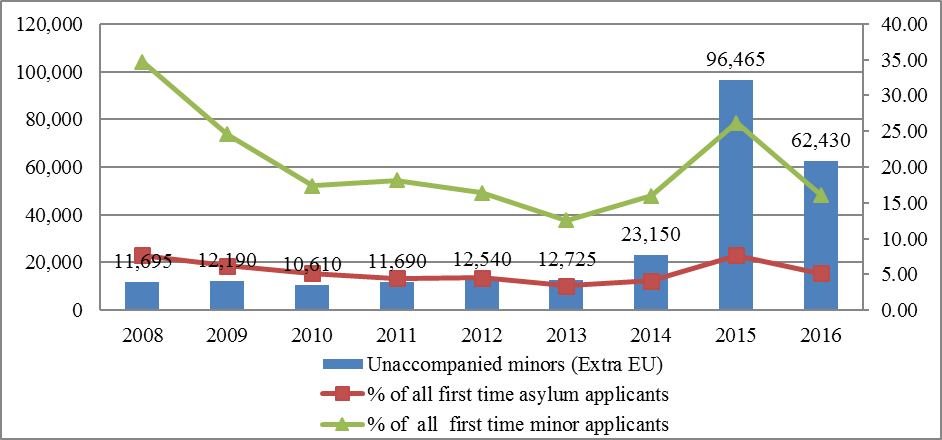

The number of unaccompanied minors arriving in the EU has grown exponentially over the last three years. According to Eurostat, in 2016, 62,430 unaccompanied minors applied for international protection in EU Member States. This is significantly lower than during the peak of the migration and refugee crisis in 2015 (96,465). It is, however, around five times higher than 2008-2013 when the equivalent numbers stood at between 11,000 and 13,000 for the whole EU. These figures are for those who were seeking international protection. They are, thus, only part of the real flow. It is hard to estimate the exact number of those who entered the EU and who were not detected by officials, but past observations suggest they are probably as many again as those who appear in official statistics. According to the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), in 2013, 12,770 unaccompanied migrant children entered the EU without seeking international protection, compared with 12,725 seeking asylum 1.

Figure 1.The number of asylum seekers considered to be unaccompanied minors and their share in the total asylum flow, and in total minor asylum applicants. (EU 28), 2008-2016

Note: The left axis stands for absolute numbers and the right axis for percentages.

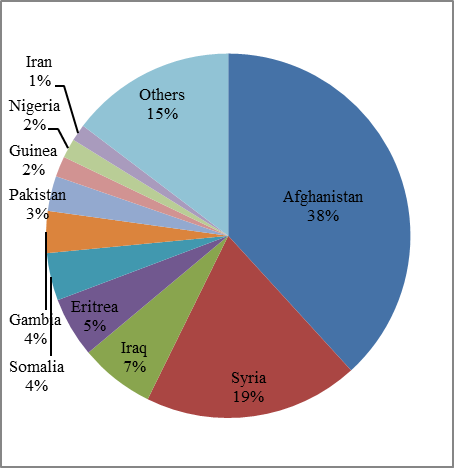

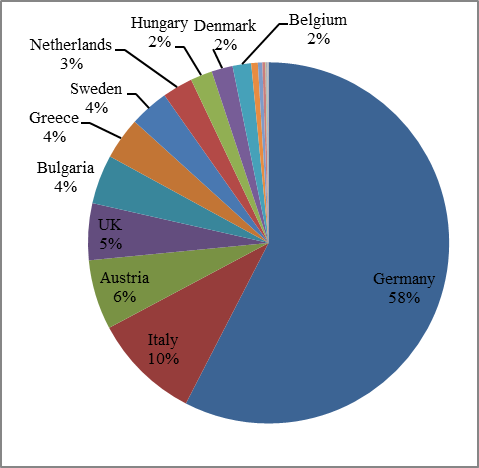

The clear majority of unaccompanied minors are male (approximately 90%), mostly aged 16-17 (70%) (Eurostat). They left their origin countries due to conflicts (63-84%) or for economic reasons (14-20%) and spent, on average, from five to seven months travelling to Europe [2]. Their geographical origins are diverse. In 2016, for instance, there were 78 origin countries. The top ten countries were (in order): Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Somalia, Eritrea, Gambia, Pakistan, Guinea, Nigeria and Iran. Between them these ten countries accounted for approximately 80 percent of the whole flow. Though the clear majority enter the EU through Central Mediterranean routes (Italy, the share of unaccompanied minors is 92% 2) and Eastern Mediterranean routes (Greece and Bulgaria), they frequently seek asylum in Germany (58% in 2016) and Sweden (24% in 2015). In 2016, only 10 percent of the total flow asked for asylum in Italy and 4 percent in Greece and Bulgaria. The observed pattern suggests the presence of a strong network effect; unaccompanied minors try for Member states where compatriots reside.

Figure 2. Main countries of origin and destination of unaccompanied minors in the EU, 2016

Origin

Destination

The figures above suggest that unaccompanied minors travel thousands of kilometres across Europe undetected. On the journey they face new threats (e.g. sexual, economic and criminal exploitation, not to mention child trafficking) in addition to those they had experienced prior to reaching the European Union. The list of challenges faced by unaccompanied minors in the EU includes the following 3:

- Dangers faced while entering the EU irregularly;

- Lack of protection while going down EU migration routes undetected;

- Lack of safe reception, reception capacity, proper reception conditions, inspection and monitoring;

- Measures to prevent movement to their preferred country of destination;

- Procedural and other obstacles to family reunification;

- The risk of administrative detention, possibly in inappropriate conditions;

- Vulnerability to sexual violence, sexual exploitation and trafficking;

- Lack of reliable information and advice, not least about trafficking;

- Lack of legal advice and support;

- Use of invasive methods to assess age, with variable results and reliability.

There is widespread agreement on the problems caused by the double exclusion of unaccompanied minors. Exposure to criminal networks, lack of health care, access to schooling and proper housing are only a few of them. As a recent House of Lords report suggests there is poor implementation of existing law and policy, a lack of cooperation (both between various actors and across Member States), then Member States are reluctant to accept responsibility, share burdens and demonstrate solidarity. To address this situation, a crucial first step would be to counter a damaging culture of disbelief and suspicion towards this group of migrants. This is damaging precisely because it leads to the loss of trust experienced by unaccompanied migrant children leaving them not only unaccompanied but also undetected and hence unprotected.

1. The figures are cited in UK House of Lords-2nd Report – Children in crisis: unaccompanied migrant children in the EU, paragraph 14 with a reference to European Commission – Written Evidence (UME0022).↩

2. Refugee and Migrant Children- Including Unaccompanied and Separated Children – in Europe. Overview of Trends in 2016, Available here ↩

3. Margaret Tuite – Supplementary Written Evidence (UME0038). Available here ↩

—

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.