Read more

Blog, Labour markets & welfare states

Do immigrants overestimate wages abroad? New research evidence

“I came to America because I heard the streets were paved with gold. When I got here, found out three things: First, the streets weren’t paved with gold; second, they weren’t paved at all:...

The key story in the 2017 Dutch election campaign so far has been the high levels of support for Geert Wilders’ PVV in opinion polls. But what explains the PVV’s ability to attract voters? James Dennison, Andrew Geddes and Teresa Talò write that although Wilders’ success is frequently linked to hardening views on immigration, attitudes toward immigration in the Netherlands have actually remained fairly stable. The real root of the PVV’s support lies in the salience of the immigration issue itself, partially heightened by media coverage of recent increases in the numbers of migrants entering the country.

2017 has been widely billed as a year of potentially momentous elections across Europe, including in Germany, France and, on 15 March, in the Netherlands. Some commentators have speculated about a domino effect that would see mainstream governments fall as part of a pan-Western backlash against globalisation and high levels of immigration following the British EU referendum and American presidential election of 2016. At first glance, the Dutch election supports this interpretation: polls suggest that the anti-immigration PVV – led by Geert Wilders – may win the most seats of any party in the House of Representatives. If Wilders’ party comes first, should we interpret the result as another example of surging public demand for an end to immigration? Or are such election results less indicative of a radical change in public attitudes than has thus far been assumed?

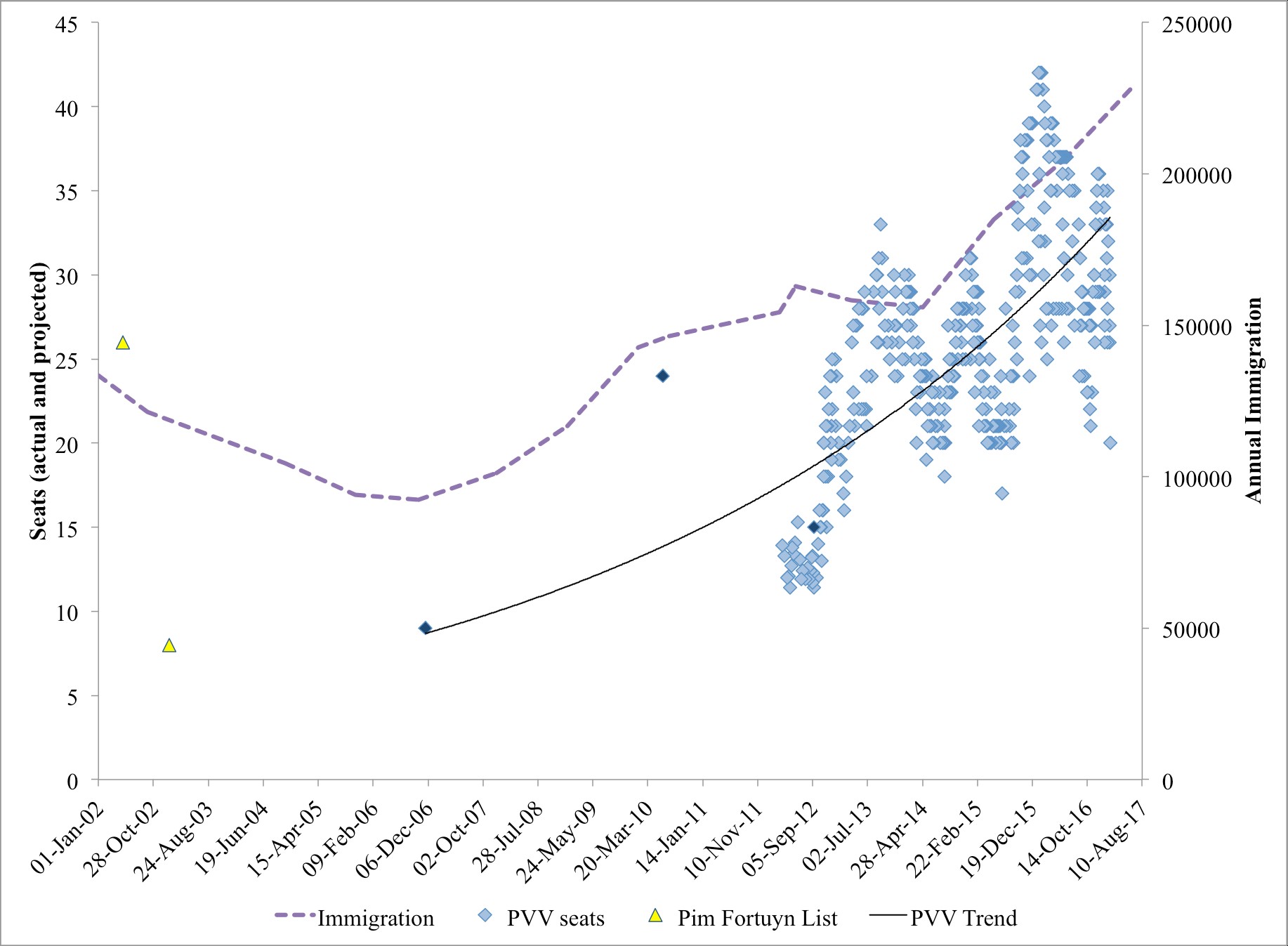

Figure 1 shows that immigration to the Netherlands and support for the PVV have risen in unison since 2011. This supports the observation that ‘ethnic change is historically associated with calls for immigration restrictions’. However, during this period we also see considerable volatility in PVV support, which was harmed in 2012 by the party’s role in the previous coalition government but then benefitted from the subsequent coalition between the centre-right VVD and centre-left PvdA.

The PVV enjoyed another boost in the wake of widely covered localised opposition to refugee settlement, an issue that has ebbed more recently though still sees half of Dutch people arguing that African migrants should be returned. Despite this volatility, the correlation between the PVV’s average annual polling and annual immigration to the Netherlands since 2011 is very strong (r = 0.85; p = 0.03; N = 6), suggestive that the PVV’s success is partially determined by actual immigration figures.

Figure 1: Immigration to the Netherlands and radical right support

Wilders claims that Islam is a ‘backward’ religion and that its followers are disproportionately sympathetic to values that threaten the Dutch way of life – with LGBT and women’s rights often cited as being particularly at risk. Focusing on Islam has been effective in the Netherlands given its history of immigration, from Indonesia and Suriname as well as Turkish and Moroccan labour immigrants. Dutch attitudes to these communities vary considerably: the primarily Christian Indonesian and Suriname communities are generally considered well integrated while Turks and, to a greater extent, Moroccans are regularly decried for their higher crime rates, weaker economic performance and supposedly languid integration efforts. From 2004 onwards, the Netherlands has experienced two further new waves of immigration – first from Poland and, in the last few years, from non-European conflict zones, with 64,000 Syrians officially residing in the country as of September last year.

Attempts by Wilders to make political capital out of anti-Polish stances – notably via the creation of a website to report crimes by Eastern Europeans – have been less successful than his anti-Islamic and anti-Syrian rhetoric, which finds a sympathetic audience amongst the 50% of Netherlanders who see non-Western migrants as a threat to their way of life.

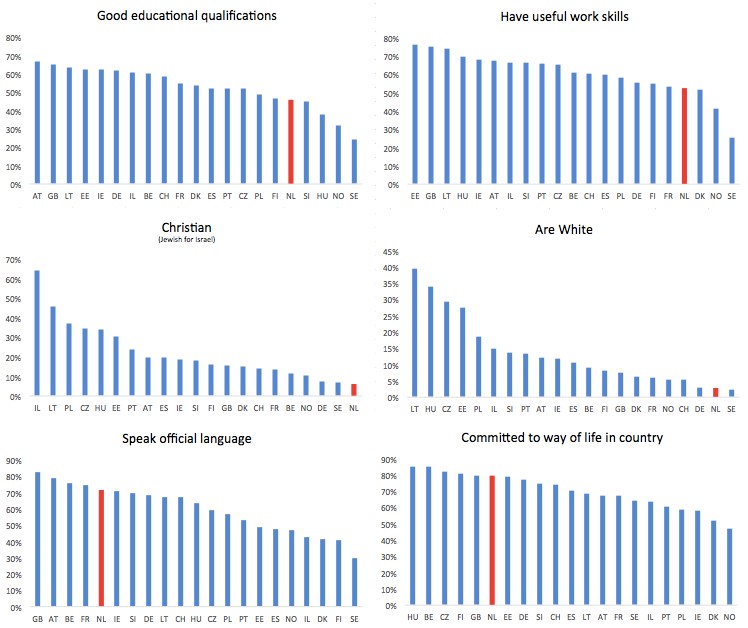

Indeed, attitudes towards immigration have a distinct bent in the Netherlands because of its strong socially liberal self-identity. The Netherlands, along with the Nordics, is generally among the most open of European countries. The Dutch seem to be less concerned than their European counterparts with migrants’ ethnicity, skills and qualifications. However, there is a notable exception over their concern with safeguarding a liberal, tolerant lifestyle (Figure 2). They are among the top five European countries in demanding that immigrants learn the native language and adopt Dutch customs.

Figure 2: ‘How important is it that immigrants have the following traits?’

Wilders’ uncompromising stance has allowed him to garner the votes of citizens with anti-immigration and anti-Islamic attitudes and make the PVV the obvious anti-immigration choice when the immigration issue is salient. Prior to the 2012 election – dominated by a close, economics-driven race between the VVD and PvdA – he could only watch from the sidelines as the PVV parliamentary representation was cut by a third. Today, the vast majority of those Dutch voters who plan to back the PVV see immigration and asylum as a motivation for their party choice (Figure 3). However, between June and December of 2016, the proportion of the population giving immigration and asylum as a basis for their planned vote declined notably from 41% to 33%, despite over 80% expressing some concern over immigration. At the same time, Wilders has suffered in the opinion polls.

Figure 3: Motivations for party choice: percentage responding ‘immigration and asylum’

More broadly, in the Netherlands and all but one other Western European country, average attitudes to immigration are fairly stable and have actually become more positive throughout the 21st century (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Mean evaluation of whether immigrants make the country a better or worse place to live in in 2002 and 2014 (scale from 0 = worse to 10 = better)

The gradually more pro-immigration attitudes of Europeans stand in contrast to the rapid rise of populist radical right parties in some European countries that has coincided with two large waves of immigration. This suggests that attitudes towards immigration at the aggregate level are not necessarily related to the number of immigrants. Instead, anti-immigration attitudes are fairly fixed and latent in social conservatives (majorities of CDA, PVV and 50Plus voters – like PVV voters – feel the advent of non-Western immigrants is a threat to Dutch values).

These attitudes are however activated and motivate party choice when the issue is made salient such as in times of high immigration levels. As such, high immigration has indeed led to the rise of anti-immigration parties in the likes of the Netherlands, France and Britain, not by turning natives against immigration but by increasing the salience of the topic amongst those who already view socio-demographic change as a risk to the national social order.

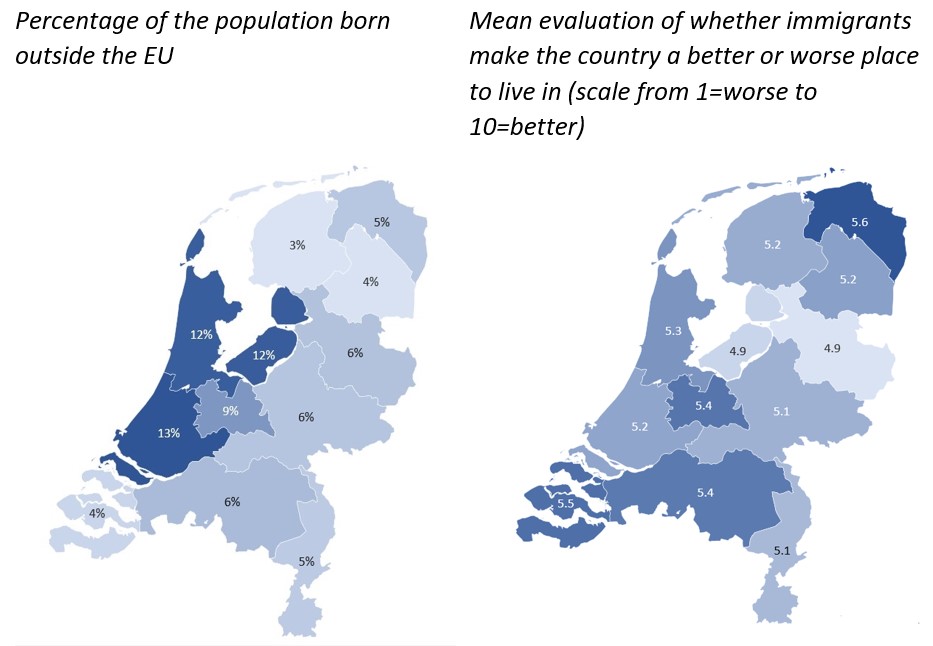

These individuals are disproportionately found amongst lower socio-economic groups who tend towards having social conservative and left-wing economic attitudes, both of which call for order and eschew ambivalence and uncertainty. Indeed, the most relevant socio-economic variable in determining sympathy to immigration is having a university education, which tends to act as a liberalising socialisation experience. The argument that anti-immigration attitudes are latent and interlinked with other ideological outlooks conforms to the often-repeated observation that regional immigration levels have no or a negative correlation with regional immigration attitudes, a finding repeated in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Non-EU population and attitudes to immigration by region

The Dutch election shows the nuanced relationship between immigration rates, immigration attitudes, and variance in the support of populist radical right parties. Higher immigration rates seem to go hand in hand with the recent surge in support for the PVV. However, attitudes towards immigration are fairly stable in the general population. Salience plays a key role in explaining the PVV’s rising performance in the polls: immigration’s salience rises along with actual waves of immigration and their coverage in the media.

In turn, higher salience mobilises citizens that hold anti-immigration stances to vote for radical right populist parties such as the PVV. In this case, the potential level of support for parties like the PVV (which currently polls at around 25 seats) is likely to be limited. Just as anti-immigration attitudes were a necessary but insufficient factor in explaining both Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, anti-immigration sentiment alone will not be enough to make the Dutch, French and German governments ‘fall like dominos’ in 2017.

—

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.

Featured image: Amsterdam, Damstraat. Credits: Moyan Brenn (CC BY 2.0).

This blog post was first published on LSE Blog on 3 March 2017