Read more

Blog, Mobility Practices and Processes

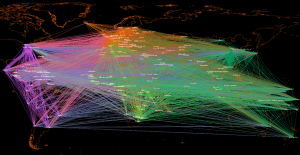

Global Human Mobility Rapidly Increasing, New Open-Access Dataset Shows

Not so long ago, you could go to an airport and find it deserted. This is no longer the case, especially in Europe and Asia, where one only rarely enters airport terminals (as well...

Fighting myths about immigration? Facts and evidence are not enough.

Disinformation and hate speech about sensitive issues such as immigration have become a major challenge for democracies. In response, calls for more evidence based policy debates are growing. Drawing upon insights about how information is processed and how understandings about migration are formed Leila Hadj-Abdou argues that instead of being fixated on facts, we should pay more attention to cognitive processes and framing effects.

There is hardly a topic today that is more in the public light and antagonizes more than the issue of immigration. Immigration debates have become ever more divisive. At the start of this year the Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán called for ‘anti-migration politicians’ to take over the European Union institutions. Consequently, there has been lots of concern about the role migration will play in the upcoming European parliament elections this May. Immigration has also been a highly contested issue in other world regions. In North America recent debates about migration have heavily centred around notions of invasion and crime. A divisive rhetoric bears consequences. In South Africa, for instance, the ongoing election campaign is said to have sparked the recent violent attacks against immigrants in Durban. The horrid terrorist attacks in New Zealand’s Christchurch also remind us that words matter.

Communication about migration in an era of polarization

It has been widely argued that we have entered a post-truth era in which myths about migration have substituted facts. In light of these development many observers, including academics, have highlighted the need for new migration policy narratives, and have called for a paradigm shift in how we talk and think about migration.

If we want to address growing societal polarization and the rise of political violence and hatred indeed communication about immigration needs to be a major concern. However, many of these pleas for a new migration narrative put the cart before the horse. What is needed before are more insights and awareness about how people, including policy makers, and other key players in the migration debate, form their understandings about immigration.

The MIGPROSP project has conducted more than 400 interviews with governance actors, i.e. people who shape and make decisions in the field of migration to explore this question. The project emphasizes that ideas about immigration are a result of sense-making processes that highlight certain (plausible but not necessarily accurate) aspects of immigration while downplaying or omitting others.

The need to think about communication beyond facts

Before discussing some findings from this research, let me point out that there is a growing academic debate that suggests that ‘facts’ are not as powerful or useful in shaping perspectives about immigration (or other contested issues) as they are often thought to be.

Why? For one, studies demonstrate that attitudes towards migration are to a significant extent rooted in relatively stable predispositions, established in early life and reinforced by later socialization.

Furthermore, we interpret facts through personal experiences. If facts do not match what we encounter, hear or see in our daily environment, we are likely to disregard them.

Often, also, there are simply no clear-cut migration facts; migration and its effects are highly contingent on their specific contexts (who, where, when, and how).

Neither facts nor numbers matter too much. It is rather how immigration is framed which has an impact on how immigration is perceived. This is related to how the human mind works, relying often on mental shortcuts (heuristics) to make judgements. Humans for instance tend to make up their mind about an issue according to what is easy to recall (‘availability bias’).

Stories that either portray migrants as victims or as threats constitute major ways of framing immigration today. Stories depicting the large middle ground between the two extremes of good versus bad migrants in turn are quasi non-existent, which makes a perspective on migrants as ordinary human beings far less ‘available’ to be recalled. It also makes it much harder for the rest of the population to relate to migrants. Dehumanizing framings have especially devastating consequences: they can deactivate processes of social cognition, spurring extreme violence towards groups framed as non-human.

In order to turn migrants into people one can identify with and relate to, and to avoid the misleading, dichotomic representation of good and bad migrants, we should also refrain from predominantly depicting them as heroes, or as helpless victims.

Mental shortcuts matter for decision making about complex issues

Migration governance actors tend to be skilled decision makers. Making decisions is at the core of their job profile. This does not imply that heuristics do not matter when they make judgements about immigration. Mental shortcuts help governance actors to make decision in a policy field that is inherently complex and characterized by constraints such as lack of time and information.

Findings by the MIGPROSP project have underlined that many governance actors do take the complexity and the variety of causes and effects of immigration into account. Many have a refined migration expertise. The research at the same time also highlights how these actors differ in what they consider the most important issues driving or resulting from international migration. For instance, governance actors in charge of immigration control and border security in Europe and North America tend to see the perception of the openness of a country by potential migrants as the key driver of immigration.

“If you say, “Welcome” without any conditions you’ve got 800,000-1,000,000 people arriving immediately. You have 300,000 people from Afghanistan arriving, suddenly. They were not coming before but they got the message.[…] , it’s a matter of fact, the situation in Afghanistan has been bad for the last 20 years, or 30 years, and that’s always been under a lot of pressure. You had the ambassador of Germany, in Afghanistan, one day his driver was not coming, he never came, then they were investigating, “Where is the driver?” He’s gone to Germany, and not legally but illegally, because he thought, “Okay, I know a bit of German, it’s possible now, and so I’m going to Germany” and so he had no driver anymore, and he had a job. People were selling their apartments in Kabul to finance their trip and go, and they had jobs in Afghanistan, in Kabul. That was the message. Now they’ve got another message, which is, “No.” (EU representative, Interview by the author, October 2017)

This understanding shapes policy responses to immigration. Walls, fences, but also information campaigns are supposed to send out a message to migrants and migration facilitators that a country is not open to immigration.

This perspective is contradicted by an understanding that focuses on push factors of immigration, such as conflict and violence in countries of origin. This perspective is foremost employed by humanitarian and civil society organizations. They argue that being tough or strident on immigration enforcement measures will not halt immigration, given that powerful ‘push’ factors, remain intact, even if supposed ‘pull factors’ are decreased.

Whilst the first perspective establishes the idea of migrants as strategic actors, the second rather sees them as victims.

These different evaluations are shaped by heuristics and the organizational context people operate in. They can differ significantly across different organizations even within the same administration/government.

Moving ahead

To conclude, we have to start developing strategies of communication about immigration that are sensitive and insightful about how humans make sense about the world surrounding them, instead of limiting ourselves to repeating mantra-like calls for evidence and fact-based migration debates. If we want to establish new ways of thinking and talking about immigration, we also have to address the composition of organizations, and diversify them, so that new perspectives can come through.

Disclaimer/Bio: Leila is currently a Teaching & Research Fellow at the Migration Policy Center & the School of Transnational Governance. She has worked in the project ‘Prospects for International Migration Governance’ (MIGPROSP) led by Prof. Andrew Geddes and funded by the European Research Council, Grant Agreement No 340430.

Affiliation/Contact: Leila Hadj-Abdou, Migration Policy Centre, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, Twitter: @leilahadjabdou