Read more

Blog, Rights, protection and inclusion

What is happening on the US-MX Border, what is likely to happen and how you can help? A response

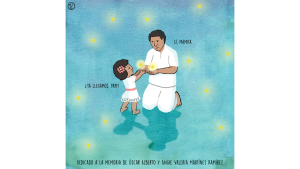

Victor Interiano, aka Dichos de un Bicho is a Salvadoran artist and creator from Los Angeles. He created Homenaje a Oscar y Valeria, the art that illustrates this blog. The following is a response...

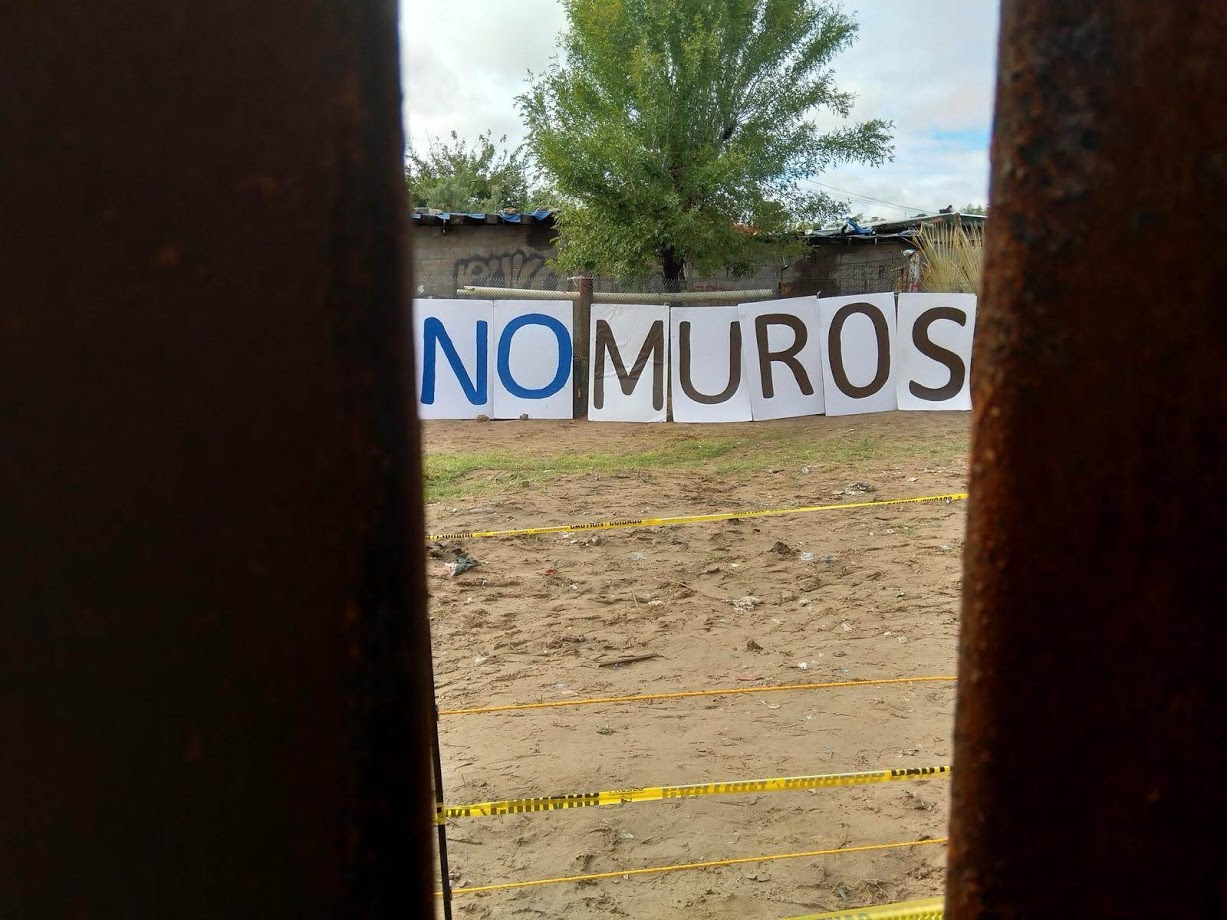

For the last few weeks, the coverage concerning the conditions faced by people arriving to the US Mexico border and those seeking admission into the US in search of protection has painted a harrowing picture of what is taking place. While there has been onslaught of information from multiple sources—which has been accompanied of photographs and narratives so graphic their nature has been questioned and at times flatly condemned—it has consistently lacked context and structure. This has undermined any potential efforts to make sense of the humanitarian crisis afflicting the people and the region. To this day the general public lacks a comprehensive, informed and critical notion of what is happening on the border, or of why understanding what is happening there matters, while the experiences of migrants –and migrants themselves – become increasingly dehumanized amid the border spectacle.

This contribution joins those made by many other scholars and policy makers seeking to situate some of the claims that have been circulated online concerning the current situation on the US Mexico border. Granted, it only includes a few of said claims, yet seeks to bring attention to dynamics that remain unexamined or that have only been discussed in passing, silenced by the dramatic images and stories dominating the social media landscape.

What is the claim? What is happening?

- Everything we are witnessing is unprecedented. Correction: not a single one of the practices taking place on the border these days is unprecedented. Testimonies of poor treatment of migrants at the hands of law enforcement officials from multiple agencies; tragic deaths; detention conditions; discrimination, have for generations shaped the experience/cultural capital of migrants and border communities on both sides of the border and beyond. One of the risks of treating them as new or unheard of is that it dehistoricizes and in the process delegitimizes the experiences of the millions of people who have experienced intimidation, violence and death on the border, and the community-based resistance and solidarity that have aimed to defend and protect migrants and their families.

- Cartels are forcing people to work for them. It is not uncommon for migrants to engage with clandestine or criminal actors of many kinds in order to attempt or achieve their mobility goals. Sadly, many times this outcome is not the result of force or coercion. It becomes an option (at times the only one) amid the complete lack of paths towards a safe, legal and dignified journey. Monolithically blaming organized crime, ‘cartels’ or ‘gangs’ for the violence migrants face exempts the states of their responsibility at creating the conditions leading people to opt for practices that involve high risk. Furthermore, it renders migrants’ decisions and agency worthless or unimportant. This does not suggest migrants face no violence. Rather it seeks to emphasize that their encounters with people who engage in criminalized activities are intimately linked to border enforcement and migration controls.

- “Traffickers (as in smuggling facilitators) work for the narcos.” Empirical evidence pointing to a structural connection between smuggling facilitators and participants of drug trafficking activities is limited, although the practice of piso (the imposition of a tax-like fee to those who use routes or territories used by drug trafficking organizations) has been extensively documented in the context of migrant smuggling. Many of the people who facilitate migrants’ journeys, however, lack ties to drug trafficking. Our research indicates that many of those facilitating segments of migrants’ journeys are instead growing numbers of ordinary people, residents of the migrant trail, who take advantage of their geopolitical and social capital to generate supplemental and (contrary to commonly held perceptions) nominal income. Most are not organized in the stereotypical fashion that the term “organized crime” often suggests.

- Smugglers have pushed adults and children into the river. The tragic deaths of people like Oscar Alberto Martinez Ramirez and her daughter Valeria were attributed to smugglers. Unfortunately, people opt for the river (and are likely to continue doing so) for that is the option most accessible to them, one that is often free of charge. In other words, on the US Mexico border, the services of a smuggling facilitator are not imperative to reach the river. True is that some migrants may have to pay to access privileged or less dangerous locations from where to cross (as this blog was being published, reports of Oscar Alberto and Valeria having paid to cross through a segment of the river emerged). But these days the main barrier between people and the river are not criminal gatekeepers but Mexico’s National Guard (15,000 of its members have been deployed to Mexico’s northern border to prevent crossing attempts).

- “Parents are putting their children at risk.” While this topic merits an entirely separate entry, it is important to emphasize that parents (not only those of migrant children) are consistently faced with having to make agonizing decisions to keep their children safe or alive. These decisions are not typically or openly shared for they are understood as deeply intimate and personal. This is a privilege the parents of the children who have died along the US Mexico border have yet to be afforded, as the voyeuristic treatment of the images concerning the death of Oscar Alberto and Valeria has shown. They are also decisions, as scholar and forensic expert Robin Reineke has written, rooted in love. “Journeys across the border are acts of love.” Migrants constantly show ‘’a model of how to show care and compassion in extremely difficult conditions.”

- CBP and ICE agents are engaging in cruel behavior. The vilification in the debate of law enforcement officials, and in particular of ICE and CBP agents (who in the case of the US Mexico border are in their majority of Mexican American origin) is one that has yet to be examined critically through the lens of race, class and gender. On the US Mexico border, careers in law enforcement and the military have been historically a path for the social mobility of Mexican Americans. For Mexican American women, who have systematically endured restrictions to specific kinds of occupations due to gender, jobs in law enforcement become important markers of status and respect. In other words, in a region that encompasses some of the poorest zip codes in the United States, a federal job is often a path into improved living conditions. Many agents and officers navigate multiple social identities as Mexican, American, foreigners, children of (formerly undocumented) migrants, etc. alongside the cultural pressures involving having to support extended families, performing traditional gender roles, and having to often distinguish/separate themselves from a past and people that are too personal and close to them (that is, the migrants they interact with). Overall frustration (‘’I didn’t sign up to be a fucking driver or a nanny”), divorce, substance abuse, depression, domestic violence, anger bouts, suicidal thoughts were frequent topics of conversation among the special agents and officers I worked with in Arizona in the late 2000s. None of this implies the treatment many migrants have reported to face at the hands of law enforcement personnel is justifiable. Neither this aims to support the claim that the behaviors reported as of late only involve ‘’a few bad apples.” Instead I seek again to contextualize the general experiences of Latino men and women working for law enforcement agencies on the border and how they must also be examined using the framework of inequality. (While research in this area is scant, the work of David Cortez, Irene Vega and Santiago Guerra, all scholars from the border, articulate important critiques).

What is likely to happen?

- Enforcement will not deter migration. People will continue to seek paths and mechanisms to migrate. However, and given the virtual absence of expedited, safe and dignified paths to do so, people will opt to travel along more dangerous routes and employ riskier strategies that without a doubt will lead to more tragedy and pain. (Reports of another child dying while crossing the river emerged on Wednesday evening).

- Efforts on the part of migrants to cross the border undetected are likely to generate increased demand for the services of smuggling guides and facilitators, many of whom lack skill or knowledge, leading to accidents and casualties. Migrants and their families will also continue to fall prey of rapacious and violent practices like scams, robberies, kidnappings and extortion, carried out by groups of varying nature on both sides of the border.

- Social tensions often grounded in xenophobia are also likely to increase. In the early hours of 1 July, a group of Cuban migrants gathered to demand collective admission into the United States at one of the international bridges connecting Ciudad Juarez with El Paso. Their efforts took place at the same time many Mexican workers employed in informal or low-paying occupations in El Paso cross the bridge to go to work. The demonstration led to the bridge’s closing. Infuriated, many of the workers physically attacked the migrants, encouraged by onlookers. Videos taken by locals show a group dragging a woman across the bridge.

- Intimidation of migrants across the United States and throughout Mexico (and not only on the border) will continue and is likely to escalate, as well as efforts to criminalize solidarity.

What can we do to help?

- Do not disseminate trauma porn.. Do not fall prey of click-bait. The tragedies–along with the unnecessary fanfare generated by the visits of presidential contenders and congressional delegations to detention facilities–will not stop, and more pictures will continue to emerge. Frankly none of us needs additional pictures to become aware or to understand what is happening.

- Think twice: how are migrants, people in detention likely to be impacted by the humanitarian and/or solidarity efforts of scholars, activists, policy makers –and lately, politicians? Demonstrations outside of detention facilities often lead law enforcement to place people in custody on lockdown “for their own good.” Visits often exacerbate the tensions between law enforcement and detainees, who can be placed in segregation for alleged misbehaviour –or in retribution for having spoken to visitors (I have yet to hear how congresspeople ensure the people they have interviewed do not face retribution or punishment for consenting to be interviewed). Bringing media to places where migrants arrive for documentation and support exposes the latter to being photographed or identified without consent and may eventually play a role in their reluctance to seek help. (It also constitutes a violation of people’s right to privacy). A research and/or documentation strategy that goes beyond extracting information or taking images is not only needed to reduce people’s revictimization: it is an ethical obligation. If by now we continue to claim we we need additional evidence of the conditions people face in detention, we are the problem, not law enforcement.

- DONATE. Shelters and NGOs can do much more with your financial support than with in-kind donations. Also keep in mind that the humanitarian emergency is not contained to the United States: thousands of people are arriving or are being returned to border cities in Mexico under DHS’s Migrant Protection Protocols. This list, compiled by Amelia Frank Vitale, contains links to organizations that accept cash donations on both sides of the border, in Mexico and in the US-Interior—where help is also needed amid the threat of immigration raids.

Gabriella Sanchez, Research Fellow at the Migration Policy Centre (MPC)

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.