Read more

Blog, Public Attitudes

Migration and the ‘rise of the right’ in South America: Is there an increasing anti-immigration sentiment in the Southern Cone?

Recent decisions and actions of some governments of the ‘Southern Cone’ of South America have created major controversies and put the migration agenda in the spotlight. Chile decided not to sign the Global Compact...

By the time this blog entry is online, the largest contingent of what has been called the Honduran migrant caravan will be approaching Mexico City, having covered mostly on foot over 1.000 kilometers from the time it entered the Mexico-Guatemala border on 18 October.

Much has been written about the caravan in the past couple of weeks and much more will be written as it continues its journey through Mexico and on to the US-Mexico border. A significant portion of the journalistic coverage has been framed by dramatic, often sensationalistic depictions of human suffering and desperation. Shots of large groups of people taken with the help of drones and sophisticated lenses by professional photographers deployed to the region solely for this event have only cemented the imagery of onslaught and crisis and the quasi-apocalyptic interpretations of migrant movement.

This blog post seeks to provide some context on the nature of the caravan. It draws from the collective knowledge of local researchers (myself included) and people on the ground. By now, some of these points have been discussed by other commentators and scholars, who have rushed to counter the outrageous claims that have circulated in connection with the current events. My aim however is to touch upon those that still mischaracterize and flatten what in fact constitutes one of the most complex, decades-long migratory processes in the Americas.1

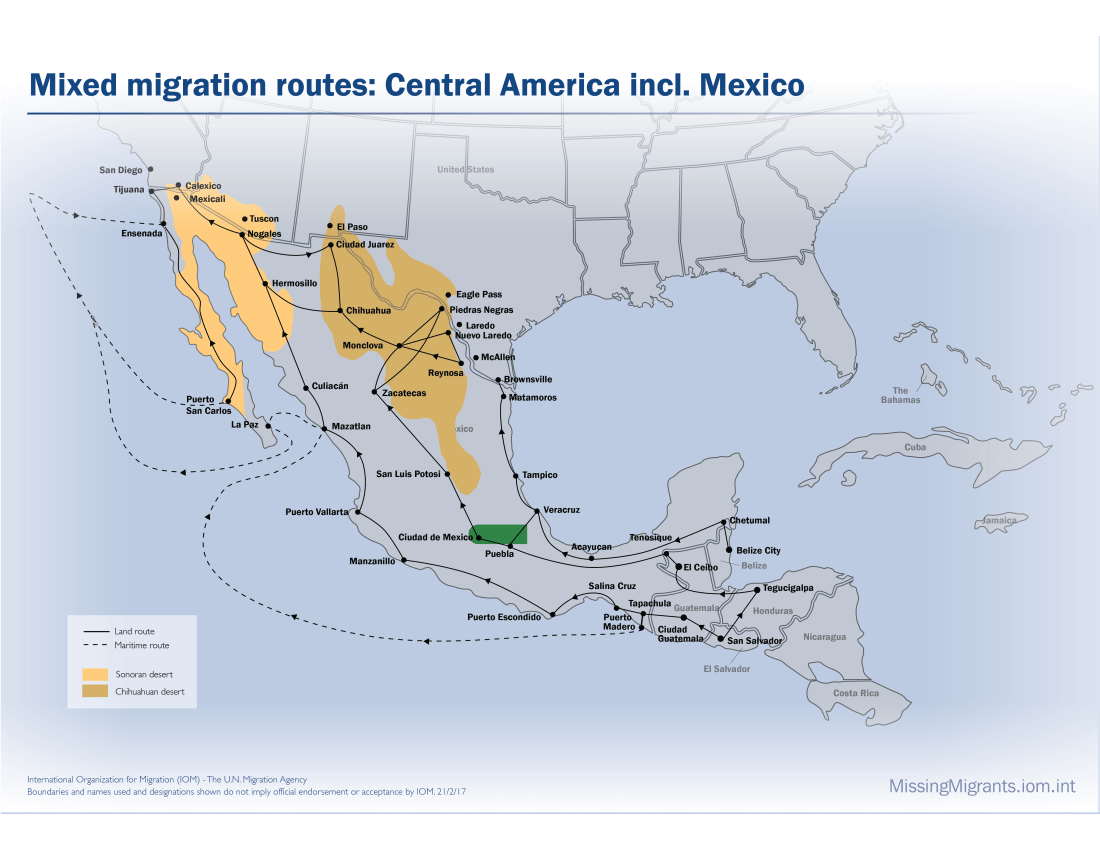

“The caravan is comprised of 4000/6000/7000 people walking at unison and more are coming.” It is easy to fall prey of what Engle-Merry refers to as “the seduction of quantification.” Estimates vary widely depending on the source. Yet apart from its numbers, it is important to understand the caravan’s complexity and motives. First and foremost, the caravan is far from monolithic. The group of people who have captured the world’s attention is primarily comprised by Honduran nationals, but people from many other countries and nationalities have joined for protection and companionship. Furthermore, caravans are far from new. Traveling in groups is a long-standing tradition in the Mexico-Central America region –one that ironically only gained visibility in the context of the upcoming US election. Central American migrants have traveled through Mexico for decades.

People have formed and joined caravans –and will continue to join the ones that will continue to form –for multiple reasons. If at all, the current events have shattered the narrow claim that Central American migration was merely the consequence of gang-related violence. The decades-long presence and role of the US in conflicts in the region; gang and state-related violence; interpersonal and intimate-partner abuse; climate change; family reunification following spousal or parental migration or deportation; persecution due to gender orientation or political beliefs; lack of jobs and educational opportunities; the burning desire to start anew, are only some of the complex factors shaping people’s decisions to move.

This caravan is not the only one traveling through Mexico at the moment. It will not be the last. It is again, just the one that has captured the most attention. Other caravans started to form in Central America and have already crossed into Mexico. A coalition constituted by mothers of disappeared and missing migrants (the Caravana de Madres de Migrantes Desaparecidos,) has also been traveling through Mexico as part of their annual journey across the country to locate their children. They have expressed their solidarity with the Honduran migrants and are likely to coincide with them during their journey. Haitian, Cuban and African migrants have also embarked on journeys to reach the US-Mexico border cities. It is estimated that 2.500 of them alone are in the border city of Tijuana, waiting for their turn to file asylum claims in the United States. And of course there are the many, many other people who are traveling on their own, in smaller groups, by their own means, away from the spotlight, their invisibility also providing them with the cover they need to move.

“The Mexican government is offering the caravan members help. Why don’t they take it?” It was reported that upon arrival to the Guatemala-Mexico border, the Mexican government issued documents to several hundred of the caravan participants. Yet information on the specific nature of such documents or the people who benefited from them varies widely. More specific were the cases of people being tricked by Mexican authorities into believing they would receive documentation to then being transported to detention-like facilities, deported or even beaten. While it is true that the visibility of this caravan has reduced the likelihood of government officials, criminal groups, and ordinary people to prey on migrants, it has far from eliminated abuse and intimidation.

Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico’s outgoing president, announced that Mexico would provide temporary work permits and CURPs (state-issued identification numbers) to caravan participants with the condition that they alerted Mexican immigration authorities of their presence in the country and only if they remained within the southern states of Chiapas and Oaxaca. Permits however were for specific kinds of jobs (low paying, seasonal work) and details on the possibility of them leading to protection and/or status of any kind were not provided. Peña Nieto’s plan –called Estás en tu Casa or “You are Home” – was unanimously rejected by the caravan’s leadership.

“Mexican people are rejecting and attacking the caravan.” Reports of attacks on migrants by Mexico’s residents have been highlighted on the media, and hate speech has also become visible online. To deny the occurrence of incidents of this nature in a country marked by its colonial past and plagued by high levels of structural violence –manifested in the form of widespread poverty, insecurity and inequality, especially along the parts of the country that coincide with the route followed by migrants – would be certainly amiss. Yet, this has been compounded by the lack of support from Mexico’s federal and state governments, which have at least twice backed out of agreements to transport the members of the caravan. The prolonged delays, changes in weather and overall exhaustion has led groups of migrants to splinter from the larger group.

Amid the lack of official responses, local, rural communities and ordinary people have provided support and care for migrants as they traditionally have. Stories of migrants who decide or opt to stay and build a life in Mexico’s countryside following accidents, illness, or incidents of robbery, kidnapping and assault as a result of the level of protection they received at the hands of locals have been long documented by scholars and NGOs. Civil society, and the shelters along the migrant trail have also for decades assisted migrants in their journeys, and are likely to continue with their efforts.

“Parents put their children in these situations.” As coverage has shown, children and women are also participating in the caravan. Here I will not engage with the rhetoric of parent-blaming that is already present in the treatment of child migrants and their journeys, for it “fails to recognize and even imperils the intimate intergenerational networks that facilitate transnational migration,” as Heidbrink and Statz have outlined. It is instead fundamental to highlight that women and children traveling in the caravan have more often those who have fallen behind, unable to keep up with the pace of the larger contingent, getting sick following days of changing temperatures, having lost their belongings or lacking the social or financial capital to continue the journey. If the prior caravans serve as an example, many migrants will return to their countries of origin. Many others will remain in Mexico, discouraged by the tone of US and Mexican anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy.

What lies ahead?

Migrant protection coalitions have launched announcements through social media warning migrants of the political tensions and the reactions that their transit have generated. These same announcements include references to the challenges people are likely to face once they reach the US-Mexico border (long waits, changes in weather patterns, petty crime, lack of shelter, etc.). Beyond Mexico, the US government has deployed an estimated 15.000 soldiers to strategic points along the US-Mexico border, despite the fact that the very US military calculates only about 20-percent of an estimated 7.000 migrants are likely to arrive to the US Mexico border, if at all. US Customs and Border Enforcement personnel have been carrying out drills on the international bridges clad on anti-riot gear and displaying high caliber weapons. In South Texas, kilometers of razor wire have been laid out, generating much fear and anxiety. While this may appear to be part of the continuum of what Nicolas de Genova has repeatedly referred to as “the Border Spectacle,” for many of us who call the US-Mexico Border home the escalation is the prelude to a new era of state violence, sadly not unknown to neither our communities nor migrants.

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.