Read more

Blog, Linking research, debates, and policies

Child migration and displacement: why we know so little and what we can do about it

In 2022, more than 100 million people were forcibly displaced; most recent reports estimate that at least 37 million of this critically vulnerable population are children and youth. Children and youth are increasingly moving...

International student flows from emerging and developing countries have grown tremendously over the last decades

In the global race for talent, more and more countries are turning to international students as a potential source of highly skilled workers. In light of the long-medium term benefits of international students, OECD countries introduced measures aimed at increasing enrolment through greater financial support, the streamlining of student visa processes as well as faster decision making on applications.

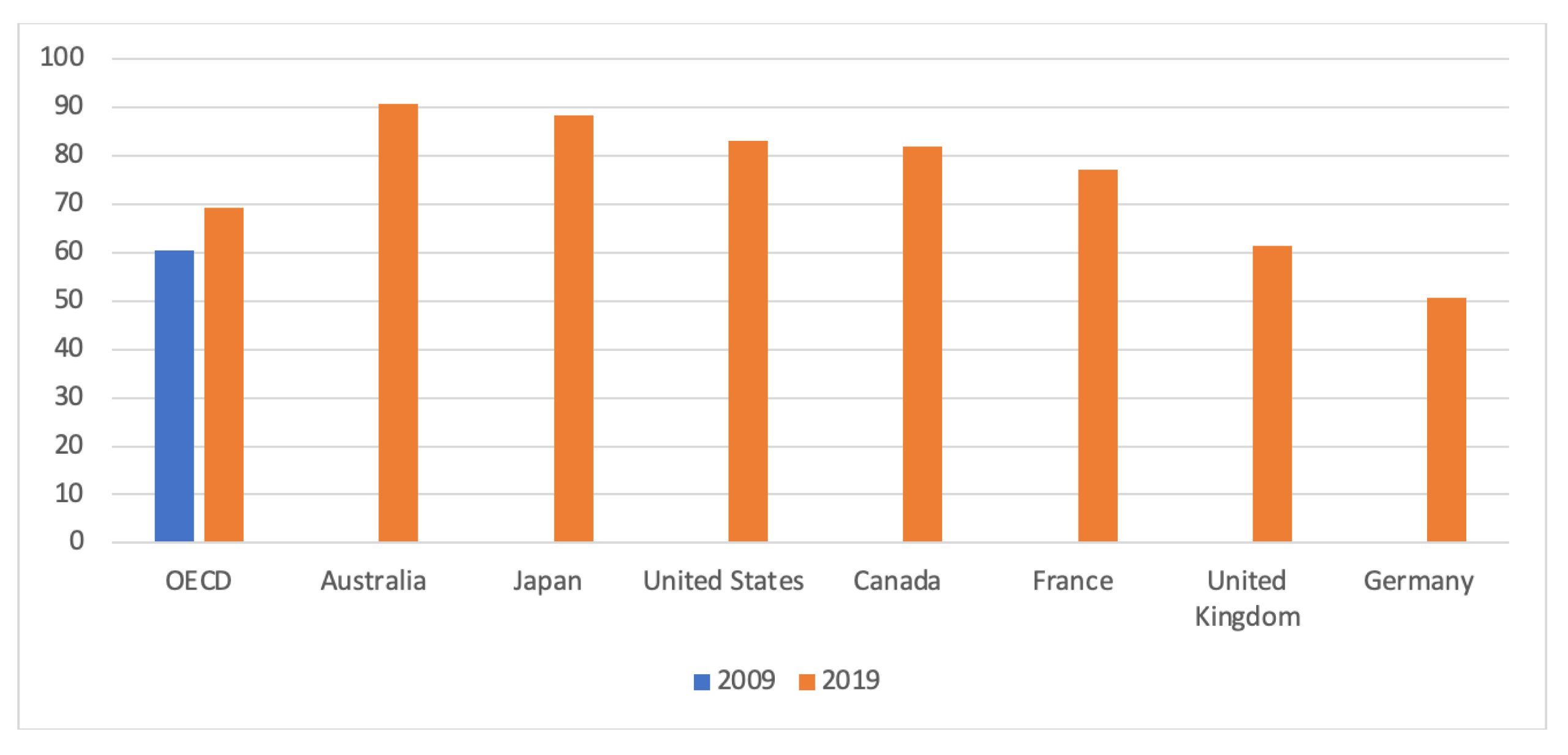

Between 2009 and 2019, the number of internationally mobile students nearly doubled to 6.1 million globally, most of them (4.2 million) studying in OECD countries. This growth was mainly driven by international student mobility from developing countries, where the rise in population has led many students to seek better opportunities abroad. On top of this, the rapid economic development in emerging economies has produced a middle class that can afford the costs of studying abroad. As a result, between 2009 and 2019, the share of students from developing countries increased from 60% to 69% in OECD countries.

Figure 1: Share of students from developing countries as percentage of the total number of international students, by host country

Notes: Elaboration from Gonnot (2023). Data for 2019 are from OECD and from the report “Education at a Glance” (OECD, 2012) for 2009. Data for 2009 are not available for single OECD members

Notes: Elaboration from Gonnot (2023). Data for 2019 are from OECD and from the report “Education at a Glance” (OECD, 2012) for 2009. Data for 2009 are not available for single OECD members

This fueled concerns about migration abuse and integrity of the student visa system in OECD countries

In the late 2000s, the increase in students’ visa applications from developing countries raised concerns about the fraudulent “misuse” of student visas – i.e., student visas used for purposes other than those for which they were designed and for illicit gain. Those include

- using the visa to enter the territory and overstay after expiration, with no intention of ever studying,

- engaging in technological or industrial espionage on behalf of their country of origin, or

- present a risk of criminal activity or terrorism.

As a result, the processing of student visa applications from developing countries appeared to suffer from statistical discrimination, with approval rates significantly lower than those of students from developed countries.

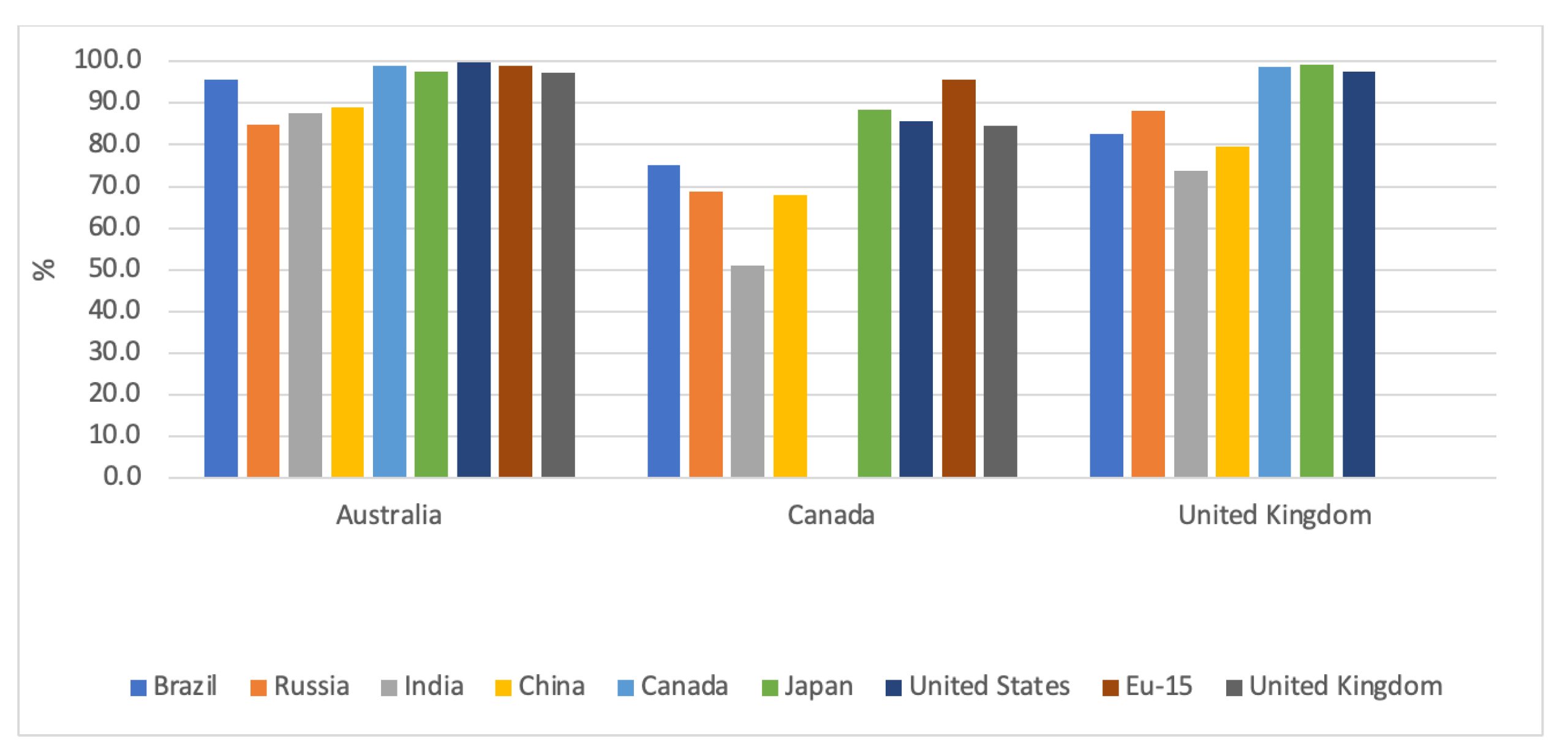

Figure 2: Approval rate for student visa applications by country of origin in 2009

Notes: Elaboration from Gonnot (2023). Data are from Department of Home Affairs (Australia), SIEP (Canada), Home Office (UK)

In light of such a trade-off between potential risks to their system integrity and the ability to attract foreign talent, several OECD countries – including Canada, France and Australia – reformed their student visa system with the aim of making it easier for visa officers to select “bona fide” students through the mandatory request of supplementary information.

Does more information to visa officers increase foreign student enrolment?

Canada’s student visa reform program

To address the relatively low approval rates of student visa applications from developing countries, the Canadian government introduced the Student Partners Program (SPP) in 2009 in partnership with the CICan association (Colleges and Institutes Canada). With the introduction of SPP, students from selected nationalities planning to pursue studies in Canada could apply to any college participating to the program. In exchange of a faster turnaround and a higher probability of seeing their visa accepted, SPP applicants from India, China, and Vietnam had to provide additional documents and certifications proving their intentions to pursue their studies in Canada.

In particular, there were two major additions to the regular application kit in order to be considered for the SPP stream, namely the

- Proofs of Language proficiency through the IELTS scores and the

- Proofs of Funds through the Guaranteed Investment Certificate (GIC), which demonstrate that student applicants had the financial resources to live and study in Canada.

SPP was initially launched for Indian students, the more strongly affected by visa problems and whose visa approval rate was only 33% before the reform kicked in. The program then quickly extended to Chinese (in 2010) and Vietnamese students (in 2016).

How the reform impacted enrolment

To estimate the causal impact of the reform on the number of Indian and Chinese students enrolled in institutions participating in the program, we use a diff-in-diff-in-diff estimator, exploiting all three dimensions of variation in the data – namely post-secondary institution, country of origin of students and time.

We find that:

- The SPP reform led to a 105% increase in the enrolment of Indian students. Two mechanisms were at play: a very significant improvement of the visa approval rate – which points to lower statistical discrimination – and a massive increase in the number of visa applications, which suggests that the introduction of SPP has also made eligible institutions more attractive.

- On the contrary, the reform had no significant impact on the enrolment of Chinese students, who faced much less difficulty in obtaining a visa through the traditional system, with an approval rate of 67% in 2009.

The SPP has thus made it possible to make an important contribution to the recruitment of foreign students from developing countries, but only when they came from a country where the perception of risks associated with fraudulent immigration was high.

Furthermore, we find that the rise in the number of enroled international students did not take place at the expense of Canadian students, and even had a crowding-in effect on non-eligible foreign students.

What can other countries learn?

The example of the Canadian reform shows that strengthening controls that improve the quality of the information available to visa officers helps reduce fears of immigration fraud and therefore statistical discrimination of students from developing countries which, in turn, support international enrolment and the immigration of “bona fide” students.

About the authors

Mauro Lanati: University of Milano-Bicocca and Migration Policy Centre (EUI). Email: mauro.lanati@unimib.it

Jérôme Gonnot: CEPII, 20 Av. de Ségur, 75007 Paris, France. Email: jerome.gonnot@cepii.fr

References

Gonnot J. (2023), Immigration étudiante en provenance des pays en développement : comment en conserver les bénéfices tout en limitant les craintes des services de l’immigration ?, La lettre du CEPII 433

Gonnot, J., & Lanati, M. (2023). Visa Policy and International Student Migration: Evidence from the Student Partners Program in Canada (CEPII WP No. 2023-07).

OECD. (2012). Education at a Glance 2011: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2022), International Migration Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/30fe16d2-en