Read more

Blog

Born into displacement: Palestinian children's struggle for rights on World Refugee Day

World Refugee Day, commemorated annually on June 20, honours the anniversary of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees—a cornerstone of modern refugee law. Yet, for Palestinians, their displacement predates even this...

It is generally accepted that all individuals, regardless of their nationality or place of residence, possess fundamental rights simply by virtue of being human. This principle of ‘universality’ is the cornerstone of modern international human rights law. While refugee rights are primarily codified in a separate branch of international law—built around the 1951 Geneva Convention—the universality principle still applies. Fundamentally, anyone seeking international protection from war, persecution, or political violence is a human being whose basic rights should be protected and respected irrespective of the country of their asylum. Yet, while the goal of universally protecting refugee rights is widely acknowledged, the reality often paints a different picture.

In this post, I demonstrate the disparity in refugee rights across countries, utilising new cross-national data gathered from recent academic research. My focus is on the extent of basic socio-economic rights afforded to refugees in developing countries, such as freedom of movement and access to healthcare and education. As you can see below, my study reveals significant cross-national variation in the provision of refugee rights not only ‘on paper’ but also ‘in practice’, highlighting that refugee rights—even some of the most basic rights—are not universally protected as host countries differ in their interests to provide or not provide certain rights to refugees.

Measuring the socio-economic rights of refugees in developing countries

To empirically identify disparities in refugee rights, I leverage (1) the Developing World Refugee and Asylum Policy (DWRAP) dataset, a pioneering study that codified de jure rights of refugees in developing countries, and (2) the original hand-coded data aimed at analysing the extent of de facto rights of refugees in major refugee host countries of the Global South between 2004-2016. Although I encourage interested readers to contact me for any technical details, these datasets enable us to gain a more systematic understanding of what the state of refugee protection looks like in different countries of the Global South.

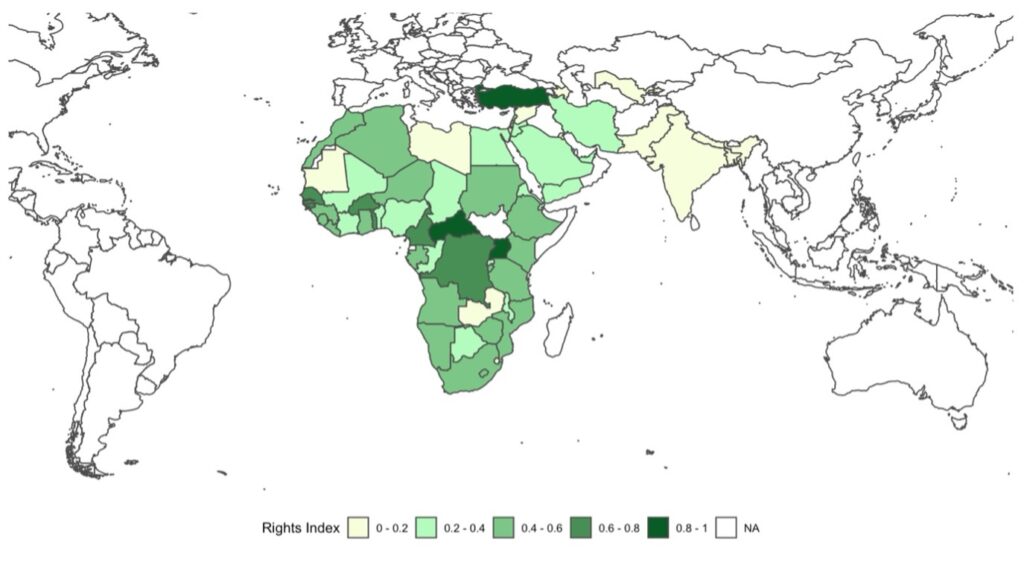

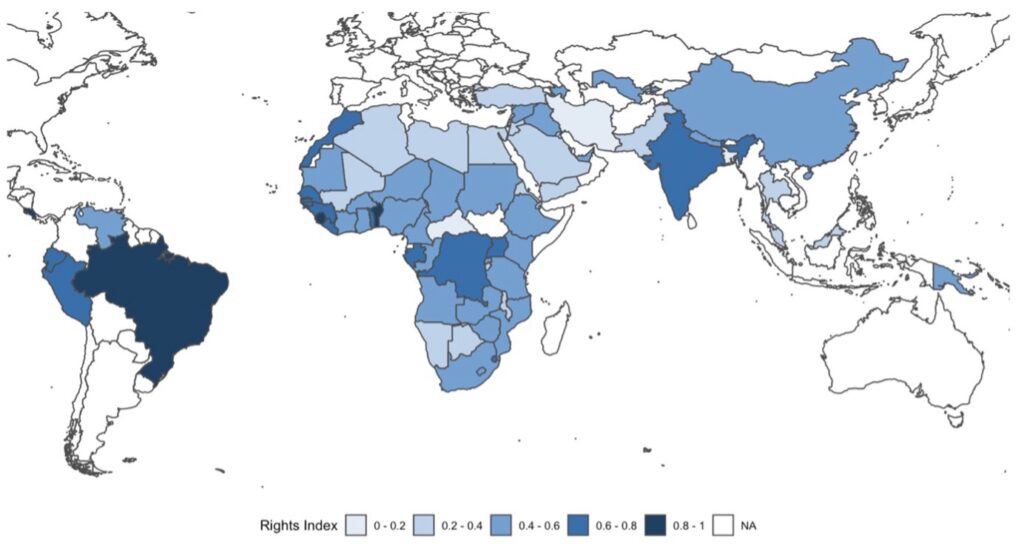

For the descriptive analysis I present below, I have constructed two summary indexes—one from the DWRAP (‘refugee rights on paper’) and the other from my data (‘refugee rights in practice’)—and projected them onto the world map in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

An index was created to evaluate how well host countries treat refugees based on various policy indicators, including refugees’ work, mobility, basic health, education, and public assistance. The scores are the inverse-covariance-weighted averages of the (standardised) policy indicators taken from each dataset on a range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better practices (i.e. more liberal and inclusive policy environment for refugees). As of 2016, the countries in darker colours in Figures 1 and 2 have provided relatively more extensive socio-economic rights to their refugee population on average.

Figure 1. Refugees’ entitlement to socio-economic rights by law in 2016

Note: The sample includes 60 countries for the year 2016. Data are taken from Blair et al. (2022). Displayed data are the weighted averages of seven policy ‘strands’ (control, settlement, employment, property, education, health, and aid) indicators, with scores ranging from 0 (most restrictive) to 1 (most liberal/inclusive).

Figure 2. Refugees’ entitlement to socio-economic rights in practice in 2016

Note: The sample includes 70 countries for the year 2016. Data are taken from Fujibayashi (2024). Displayed data are the weighted averages of seven policy indicators (mobility, work, self-employment, property, education, health, and social assistance), with scores ranging from 0 (most restrictive) to 1 (most liberal/inclusive

So, how universally protected are refugees’ rights?

A few key takeaways from the descriptive evidence presented above are:

#1 There is significant cross-national variation in the developing countries’ provision of refugee rights

As you can see in Figures 1 and 2, there is a great deal of variation across countries in the extent of rights and freedoms refugees can enjoy in their host country, both by law and in practice. To put it differently, some countries create a more inclusive host environment—either ‘on paper’ or ‘in practice’, or both—while others do not. The displayed maps provide cursory evidence of the fact that refugee rights are not very universal as opposed to a popular ideational belief.

#2 There is some discrepancy between refugee rights ‘on paper’ and ‘in practice’

While cross-national variation is measurable in both de jure and de facto dimensions, these variations are not all the same. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are several countries that have a relatively more liberal or inclusive legal framework for refugee rights, but these legal provisions are not well translated into their practices (e.g. Türkiye). Similarly, there are a few countries that are ranked lower in the de jure scoring but not necessarily so in the de facto scoring (e.g. India). These examples imply that studying the state of de jure refugee rights is important, but it cannot tell everything about the de facto, namely the extent of rights refugees can actually enjoy in their host country. Further exploring the gap between de jure and de facto rights of refugees would be an important topic for future research.

#3 There is some regional clustering concerning the provision of refugee rights in practice

In Figure 2, those countries with higher scores tend to be concentrated in specific regions such as West Africa or Latin America (though a similar trend is far less obvious in Figure 1). Both regions are known to have developed relatively liberalised regional instruments, which could have some impact on the refugee-hosting practices of some regional countries.

Conclusion

My objective here was to illustrate the state of refugee protection landscapes in today’s world using some of the recently developed data in academic research. As shown, the country to which refugees migrate does matter since the treatment refugees experience in one country differs from what they would likely experience in another one. To what extent refugees really have the ability to choose their preferred destination is a different question, but my study shows that refugee rights are not universally protected in reality and there exists a cross-national variation in the provision of refugee rights both by law and in practice.

What has been widely known is that state sovereignty remains the bedrock of today’s international refugee regime, which many scholars have considered ‘broken’ over many years. And this is strongly related—and arguably endogenous—to why the extent of rights and freedoms afforded to refugees and other protection-seekers differs from country to country. Admittedly, the existence of such a cross-national variation is not overly surprising to many refugee and forced migration scholars, but we often skip answering what the variation looks like. The hope is that my research can shed some empirical light on this point and help many scholars and policymakers to gain a better grasp of the existing refugee protection challenges across the Global South.

—–

Hirotaka Fujibayashi is a Max Weber Postdoctoral Fellow at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute. You can follow him on X, visit him on LinkedIn or contact him at Hirotaka.Fujibayashi@eui.eu.