Read more

Blog, Labour markets & welfare states

Challenging the Myth of the Undesirability of Low-Skilled Labour in the EU

When EU countries visualise an ideal immigrant, a highly-skilled and educated immigrant comes to mind. For many, the highly-skilled and skilled represent the only ´legitimate´ form of immigration. EU immigration policy in its current...

Executive Summary

EU’s Global Approach to Migration and Mobility (GAMM) highlights the importance of evidence-based policymaking which, in turn, depends on the accurate measurement of migration in the EU and its neighbourhood. This short piece gives a brief insight into the problems associated with statistical data collection on labour emigration from the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood to the EU and the need for its reform.

Background

EU’s Global Approach to Migration and Mobility (GAMM)[1] highlights the importance of evidence-based policymaking which depends on the accurate measurement of migration in the EU and its neighbourhood. The knowledge tools included in GAMM – such as mapping instruments, impact assessments and migration profiles – need credible sources of data on migration to enable policymakers to make informed decisions. In the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood[2] (hereafter, referred as the ‘region’), statistics on labour emigration are usually derived from administrative sources, which have remained largely unchanged since their creation in the post-Soviet era. The other sources are represented by specific one-off small-scale surveys conducted by governmental or international agencies.

Main challenges with the statistical data collection on labour emigration

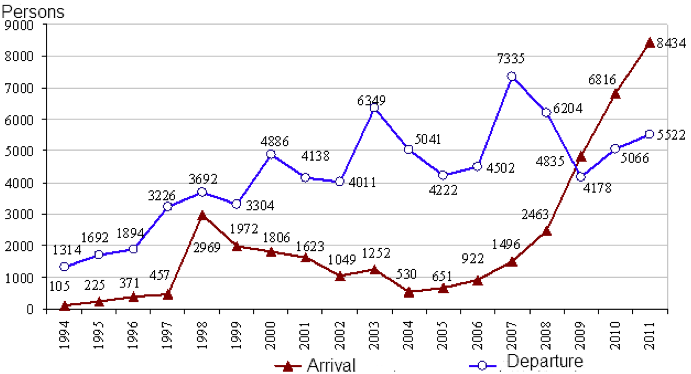

- Administrative sources Firstly, administrative sources, such as the registration of labour migrants on the basis of official labour contracts, tend to be largely incomplete and scarcely usable. In Belarus, for example, labour movements are not classified by country of birth/nationality which makes it impossible to detect the nature of flows. In Graph 1 (see below), the administrative data on flows of labour migrants in Belarus indicate that 5,522 labour migrants departed Belarus in 2011. However, in the same year, only in Poland, 10,788[3] first residence permits for work reasons were granted to Belarus citizens. Though these flows are not entirely comparable, the magnitude of the gap in the statistical data is quite striking.

Graph 1: Arrival and departures of labour migrants from and to Belarus on the basis of official labour contracts and agreements (1994-2011)

Source: Registration cards for labour migrants, Belarus (Bobrova and Shakhotska 2012[4]), Visit CARIM-East[5] website for more details

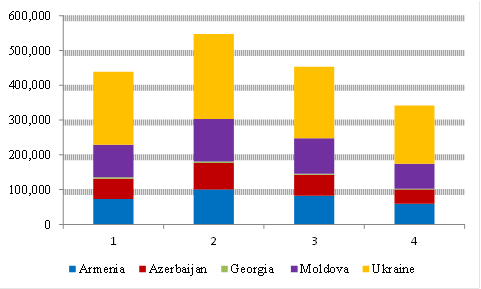

Moreover, administrative sources do not capture migrants at the destination point. It is often the case that in the semi-open border regimes (as is the case in the EU and CIS[6]) circular migrant workers do not apply for work permits, especially if performing seasonal or temporary work. Therefore, there movements are lost in the administrative statistics. For example, Belarusians do not need a work permit to work in the Russian Federation, and thus, they are simply absent from the statistics (as depicted below in Graph 2). Similarly, the number of permits issued to Moldovan labour migrants in Russia is below estimations (if compared for example with the Moldovan Labour Force Survey).

Graph 2: Temporary work permits issued to Eastern Partnership[7] (EaP) country citizens in the Russian Federation (2007-2010) *

*Notes: Migrant workers from Belarus are not included in the statistics as they do not need work permits in the Russian labour market in accordance with the Agreement between Belarus and the Russian Federation on the establishment of the Interstate Union.

Source: Federal Migration Service (FMS), Russia. For more details, visit CARIM-East database www.carim-east.eu

Finally, administrative sources have complicated procedures and contradictory legal norms. For example, in Armenia, the Population Register only provides for the possibility of registration at a place of permanent residence (de jure population) but excludes the possibility to register at a temporary place of residence (de facto population). Due to the complicated procedure of registration and de-registration, migrants do not have any incentive for complying strictly with the rules of registration. This primarily means a significant underestimation in emigration and immigration flows. Similarly, in Russia, the absence of a legal time criteria makes it difficult to separate temporary stay from permanent residence. This implies that large numbers of immigrants prefer to register as temporary migrants (i.e. in their place of stay), though the duration of stay may last several years. Unfortunately, temporary migrants’ registrations are not processed by official statistics, implying that their numbers are unknown.

- Specialized surveysThe only information on emigration in most EaP countries is to be found through specialized surveys such as the Labour Force Survey (LFS). They usually collect a wealth of information that allows for some basic analysis of migration trends and characteristics in the region.However, there are three main problems with these surveys. Firstly, apart from LFS, surveys tend to be one-off undertakings and differ in methodology or objective, ruling out any possibility for comparison in time and space. This can be seen in the case of the survey conducted by the Ukrainian State Statistics Service in 2008 in cooperation with the Ukrainian Centre for Social Reforms, the Open Ukraine Foundation, IOM, and the World Bank. This survey was repeated in 2012 and, thus, there might be a potential for some comparisons. Also in 2008, a survey was conducted in Georgia on the topic of “Development on the Move: Measuring and Optimising Migration’s Economic and Social Impacts”[8]which was a joint project of the Global Development Network, and the Institute for Public Policy Research. If not repeated with the same methodology, the data from the survey will become out-dated and useless for the future studies.

The second problem with surveys is the heterogeneity of the applied definitions of migrationwhich makes comparison of the received data difficult. Different definitions of migrants (e.g. based on country of birth/citizenship/previous residence criteria) are often used interchangeably and applied to migration analysis.

Finally, a key concern to be highlighted is that surveys usually take only a small sample of migrants leading to issues of statistical representativeness.

Good source of statistics = Effective migration policy?

It is clear from the above discussion that the statistical data collection system in the region is in need of urgent organizational and structural reform with functional expansion, better financial support and more human resources. More specifically, the following reforms should be implemented:

- Currently, the most useful and updated data on labour emigration characteristics in the region is gathered by labour force surveys. However, at the moment, only Moldova has a special segment in its survey dedicated to emigration. It would be beneficial for other countries in the region to conduct similar surveys regularly in their territory with special modules that capture out-migration of household members as well as return migration.

- Both EU and the Eastern Neighbourhood countries would benefit from specific efforts bridging the results of their respective labour force surveys and making sense of the circular mobility captured by this source at both ends of migration. Possible gaps and inconsistencies, if identified, should be further examined by focused surveys.

- There should be the establishment of harmonized Population Registers in all the countries in the region.

- More centralized mechanism for the gathering of emigration data and better coordination should be conducted between the various state agencies responsible for emigration-related issues

- Qualified methodical assistance and consultations with foreign research institutions should be provided so that the data collected meets the international requirements for international migration statistics

Please Note: The above discussion is drawn from MPC’s explanatory notes on ‘Statistical Data Collection on Migration’. To read the detailed notes, visit: http://www.carim-east.eu/publications/explanatory-notes/statistical-data-collection-on-migration/

Anna di Bartolomeo, Research Assistant to CARIM East, CARIM India and CARIM South

Neha Sinha, Policy Analyst to the MPC

—

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.

[1] Source: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/international-affairs/global-approach-to-migration/index_en.htm

[2] For the purpose of this paper, the analysis of the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood includes Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan

[3] Source: Eurostat

[5] CARIM-East is part of the Migration Policy Centre (MPC) and is the first migration observatory focused on the Eastern Neighbourhood of the European Union. The project covers all countries of the Eastern Partnership initiative (Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) and the Russian Federation www.carim-east.eu

[6] CIS refers to the Commonwealth of Independent States which is a regional association of former Soviet Republics

[7] The Eastern Partnership Initiative (EaP) is an institutionalised forum between the EU and the post-Soviet states: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine