Read more

Blog, Mobility Practices and Processes

Did International Mobility Boost the Covid-19 Pandemic? Questioning a Commonplace Idea

In his 2007 best-seller, The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb wrote: ‘As we travel more on this planet, epidemics will be more acute […] and the successful killer will spread vastly more effectively’. Was this...

For those working to promote a positive and more balanced view about migration in high-income countries, the world can seem a bleak place at times. From drownings in the Mediterranean, to detention centres in Libya, the Trump administration’s “Muslim ban”, and restrictions on labour migration and regular employment, policymakers appear to be increasingly enacting policies that make both immigration and inclusion more difficult.

To justify these moves, policymakers often fall back on supposedly negative public attitudes to immigration. Even those who would like to enact more positive policies feel restricted by the range of options that their constituents would support. Yet, as we show, this is based on a narrow understanding of how the public feels about immigration.

Most people are neither pro- nor anti-immigration but fall somewhere in between, termed the ‘anxious’, ‘conflicted’, or ‘movable’ middle. Such people tend not to have strong ideological preferences but are united by common values and beliefs. They are usually relatively open to changing their views about immigration – hence they are ‘movable’ – but they also have genuine concerns. These concerns are often targeted by political actors, including those spreading disinformation and hostile narratives, making these groups a key ‘battleground’ in terms of shaping attitudes to migration.

This blog, based on new research by the Overseas Development Institute and the European Policy Centre,[1] will focus on how those who seek to promote open attitudes to immigration can understand and shift the views of the movable middle. But why focus on them at all? Why not just mobilise those already pro-immigration? Because this merely moves passive allies into active allies, which is important but insufficient. Within the “spectrum of allies”, progressive groups also need to earn support from those in the middle, thereby contributing to normalising the debate and increasing the number of people in favour of positive change.

Understanding the Movable Middle

In late 2020, Gallup updated their Migrant Acceptance Index for the first time in three years. It found that, across the world, support for migrants had decreased. Mass refugee movements, rising unemployment, and economic downturn could all have contributed to this. The Index also notes that “people are even further apart… than they were before”, highlighting a general trend towards polarisation of views on immigration.

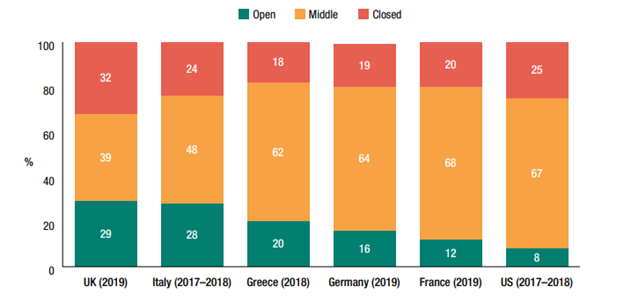

In this context, it may be tempting to focus on the declining average, or those on the fringes who shout the loudest. But doing so obscures the fact that, in many high-income countries, the movable middle forms the majority (as figure 1 shows for the UK, Italy, Greece, Germany, France, and the US).

Figure 1. Grouping people based on their attitudes (including to immigration) in six countries

Note: Source data for Germany totals 99 percent due to rounding. A new study by Juan-Torres et al (UK, 2020) has found less evidence of a ‘movable middle’, suggesting views may be shifting in the UK.

Sources: HOPE not hate (UK), Demoures (France), Dixon et al. (Greece), Hawkins et al. (US), Dixon et al. (Italy) and Krause and Gagné (Germany)

The movable middle is made up of different groups of people in different countries. Academic researchers and organisations such as Purpose have attempted to segment these groups based on their values and views on a range of subjects, including immigration. Such ‘attitudinal segmentation’ can help to better understand the values that these groups have in common and fine-tune advocacy efforts to turn them away from hostile narratives, including those spread by disinformation. In what follows, we consider the characteristics and beliefs of three broad groups that can be identified in each of the countries in question.

The Disengaged

E.g. UK Anxious Ambivalent, Italy Disengaged Moderates, Germany Detached, France Disengaged, and US Politically Disengaged

People in these groups tend to be young, working class, and individualistic. They are less likely than other groups to vote, identify with a political party, or be politically active in other ways (e.g. protest, donate, run for office). They see politicians as incompetent, and the system as ‘rigged’. Most are unsure about whether immigration benefits their country economically, but many do have concerns about its cultural impact. For example, in the US, those who are politically disengaged are the most likely to say that being white is necessary to be American. These groups are particularly susceptible to hostile narratives about migration, given their comparatively high levels of distrust.

The Disillusioned

E.g. Italy Left Behind, Germany Disillusioned, and France Left Behind

People in these groups tend to be older, either middle-aged or retired, with relatively low education levels and living in more rural areas. They are often characterised as those ‘left behind’ by economic progress. While they recognise the economic success of their country, they do not feel that this success is trickling down to them and are therefore worried about economic challenges. This can translate into less support for labour migration, as they feel that immigrants are putting pressure on economic resources. They recognise that immigrants work hard and that they take roles locals do not want. However, their frustrations can be manipulated and directed against groups that are presented as a threat to their interests.

The Traditionalists

E.g. Greece Detached Traditionalists, Germany Established, and US Traditional Liberals

People in these groups tend to be older, retired, and with high levels of religious adherence. They are often patriotic, nostalgic, and have high levels of trust in institutions including political parties and the media. Most are comfortable with their place in society and feel they have had many opportunities in life. They are generally open to compromise and have a strong belief in fairness. As a result, many of them have strong humanitarian values. However, they also want to preserve what they feel are the strengths of their society and (religious) heritage from outside influences, and they may be concerned about new groups culturally different to themselves.

How the Movable Middle is Targeted with Hostile Narratives

These groups in the movable middle hold complex values that do not neatly conform to pro- or anti-migration sentiments. Researchers have shown that a broad spectrum of right-wing campaigners systematically appeal not only to beliefs commonly associated with anti-migration sentiments, like tradition and conformity, but also to those traditionally associated with pro-migration sentiments, such as benevolence. In so doing, they can adjust messages to effectively resonate with the values of their audience – while also appealing to their concerns.

Each of these groups typically share concerns about cultural identity, unemployment, or security. As a result, they are also highly susceptible to manipulation, such as disinformation that seeks to exploit their concerns and expose them to hostile narratives.

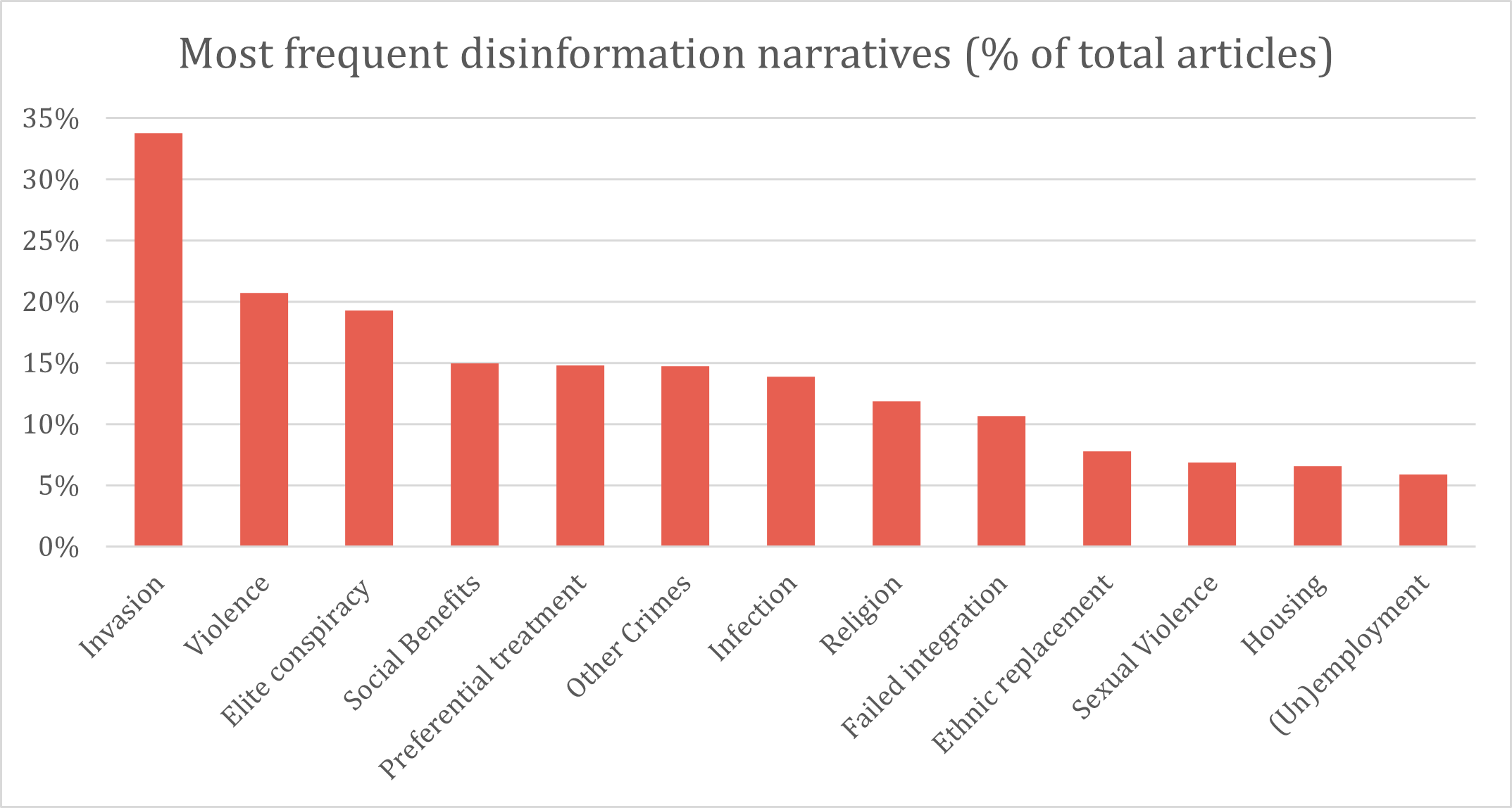

For example, The Disengaged have low levels of trust in institutions and are therefore likely to be open to narratives alleging conspiracy or corruption on the part of elites. They may also respond to claims of migrant ‘invasion’ or violence, which may underline their feeling that migrants are culturally incompatible with their host societies.

The Disillusioned have the greatest economic concerns and are therefore likely to be influenced by narratives about migrants taking scarce community resources, such as social benefits, and/or benefitting from preferential treatment.

Finally, The Traditionalists are likely to respond to identity-related narratives emphasising supposed differences between migrants and locals, such as religion. Narratives that stress a changing society or migration being ‘out of control’ could speak to their values of nostalgia and fear of change.

Our research demonstrates that these narratives are frequently promoted by disinformation sources and other hostile messengers across European countries, likely with the intention to influence the movable middle. While disinformation is not the only technique used by anti-immigration campaigners, this research serves to illustrate how false narratives are constructed to appeal to the groups mentioned above.

Figure 2. Disinformation narratives in Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Czech Republic

Note: Researchers from the European Policy Centre collected and analysed a total of 1,425 news articles published online in four EU member states (Germany, Italy, Spain and the Czech Republic), published between May 2019 and July 2020, that spread disinformation and misinformation about migration. Figure 2 shows some of the most frequent disinformation narratives across the four monitored countries (percentage of the total number of articles).

Responding to Hostile Narratives

Although hostile narratives are often based on disinformation, ‘myth-busting’ will not necessarily prevent them from reaching the movable middle. Hostile narratives tap into their sincerely held concerns and resonate with their values. Those who are exposed to them will likely disregard the facts if the emotional appeal is strong enough.

Instead, those who want to make the movable middle more open to migration should promote alternative narratives that resonate with lived experience, particularly acknowledging the values and concerns held by the movable middle. Below we provide some examples of how this has been done in practice: exploring shared ideals and experiences and highlighting contributions.

Exploring Shared Ideals and Experiences

As stated above, many in the movable middle are concerned about cultural change. To combat these concerns, alternative narratives could focus on promoting what migrant and local communities have in common – both historically and today.

Welcoming America has launched a toolkit that presents immigration as a historical and normal phenomenon while couching this narrative within explicitly American notions of patriotism, freedom, and courage. As they put it, “we believe that moving to make a better life for your family is one of the hardest things – and one of the most American things – a person can do.”

Similarly, in the UK, campaigns by British Future have focused on representing shared national traditions. Such campaigns can exploit national symbolism or the visual representation of the values shared by groups in the movable middle. One campaign launched a ‘poppy headscarf’, marking the centenary of the first Victoria Cross for a Muslim soldier. Another focused on the contributions of all races and faiths to the success of the England football team.

Finally, to appeal to those who belong to groups cherishing religious traditions, it is possible to target values pertaining to religion in order to foster inter-faith dialogue. For example, local Christian groups in the UK played a key advocacy role for the establishment of a new Muslim prayer centre.

Highlighting Contributions

COVID-19 raised health-related concerns, and groups spreading disinformation tried to associate migrants with an infection risk. However, it also provided opportunities to showcase the vital role of migrant doctors and other key workers during the pandemic. This demonstrates the importance of responding and adapting to new developments to promote a positive and more balanced view about migration.

Even in more normal times, narratives highlighting the social and economic contributions of migrants can resonate with readers. For example, for those movable middle groups concerned about security, narratives could focus on those migrants who work as firefighters or policemen, showing them as a source of safety and protection.

Highlighting these contributions appeals to the priorities and values of those in the movable middle who aspire to build healthier, fairer, and more prosperous societies. It showcases that all are working side by side to build stronger economies and more cohesive communities.

In so doing, those who seek to promote a balanced discussion should avoid reproducing cliches of migrants as victims or heroes. Painting immigrants as “exceptional” is more likely to just minimise or ignore the existing concerns of the movable middle, rather than attempting to overcome them.

Guiding Principles for Winning Over the Movable Middle

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to winning over the movable middle. Alternative narratives that work to combat one hostile frame may not work for another. What works for a ‘traditionalist’ group in Germany, may not work for a similar group in France. Alternative narratives need to take account of the hyper-local values held by their target groups and frame their messages accordingly.

Those in the movable middle may not necessarily be immediately receptive to this kind of messaging. To break through any initial resistance and gain their trust, pro-migration advocates should not only focus on the ‘what’ but also on the ‘how’. Working with messengers such as faith leaders, sports personalities, and other figures trusted by those in the movable middle can be useful.

Advocates of migrants’ rights and groups trying to create more welcoming societies should also work through in-person exchanges other than social media, as sustained intergroup exchanges can stir empathy and rebuild trust.

Finally, some words of warning for those attempting to employ alternative narratives. It is easy to get swayed by the views of those who are pro- or anti-migration, especially if they are shouting the loudest, despite the fact that they represent a minority of people. Those who seek to win over the movable middle should ensure they focus on the values they hold and employ narratives that are coherent with their worldviews.

[1] Paul Butcher and Alberto-Horst Neidhardt, “Fear and lying in the EU: fighting disinformation about migration with alternative narratives” (2020). The Issue Paper is the result of a collaboration between the Foundation for European Progressive Studies, the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, the Fundación Pablo Iglesias, and the European Policy Centre. ↩

Paul Butcher, European Policy Centre

Helen Dempster, Center for Global Development

Alberto-Horst Neidhardt, European Policy Centre

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.