Read more

Blog, Rights, protection and inclusion

What the Essex case tells us about the current state of migrant smuggling from Europe into the UK

The devastating events of last month in Essex involving the deaths of 39 people traveling in the back of a lorry have generated an onslaught of commentary concerning the current state of migrant smuggling...

The demographic composition of most countries has changed dramatically in the last decades. The questions of how different people with different backgrounds can peacefully interact in the modern and more globalized world, and how their societies may prosper, are among the most important challenges of recent years. There has been a growing interest among social scientists and policymakers in studying and uncovering the role that different types of diversity play in shaping social, political and economic outcomes. Exploring this issue is extremely important and relevant to a range of different public policies, including policies relating to immigration and integration.

How can we, and how should we, measure ethnic diversity? These are hard and highly contested questions. A fundamental problem is that there is no widely accepted and uniform definition of “ethnicity”. Group identities are complex and mostly socially constructed, which means that quantifying and measuring them is inherently problematic. There can be multiple ways of specifying different “ethnic groups” in a country, with no one obvious “best” way of doing so. Questions related to the definition of diversity become even harder in comparative research that involves multiple countries, each of which often has its own concept of ethnicity.

Why change over time matters

Definitional issues aside, I argue that a major problem with a large part of existing social science research on the effects of ethnic diversity is that diversity is treated as an exogeneous variable that does not vary over time. A recent study by researchers at Princeton University and the University of Oxford shows that although initially threatened by change, people adapt to societal diversity over time. Research that treats ethnic diversity as time-invariant has made limited progress in learning about its long-term effects.

Why is it important to study the effects of ethnic diversity over time? Because a increase or decline in ethnic diversity over time might have very different consequences. For instance, countries with steadily increasing ethnic diversity might be more willing to introduce institutions that effectively manage problems connected to more heterogeneity in the population than countries with shorter histories of ethnically diverse societies and with lower average rates of diversity change. On the other hand, in some instances (such as in the case of the dissolution of multi-ethnic states) ethnic diversity may decrease rapidly posing completely different challenges to the newly-homogeneous societies. Not taking into account these historical developments might seriously hinder our understanding of the effects of ethnic diversity.

The new index

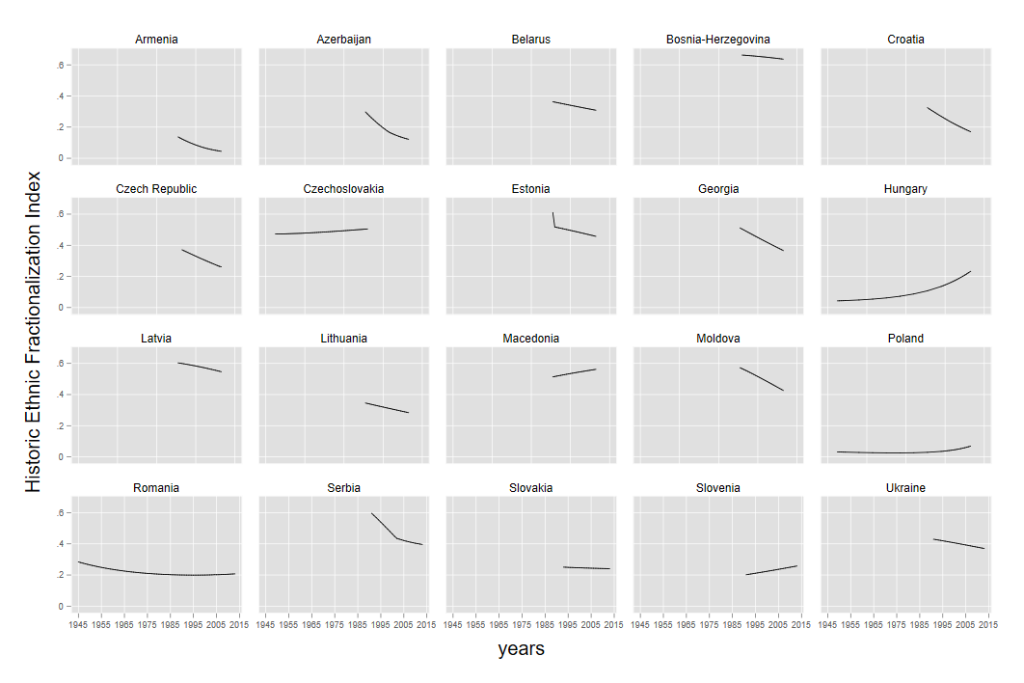

For this reason, I have developed a new Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization (HIEF) dataset. It contains data on ethnic fractionalization in 162 countries for each year in the period 1945 – 2013 (see Figure 2). Fractionalization (sometimes also referred to as fragmentation) indices measure diversity as a steadily increasing function of the number of groups in a country. They are based on the probability that two randomly drawn individuals from a country belong to two different groups. Theoretically, fractionalization indices range from 0 (when all individuals are members of the same group) to 1 (when each individual belongs to his or her own group).

The Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization (HIEF) is a natural extension of previous ethnic fractionalization indices. It is also quite easy to compute. Firstly, I derived data on the percentage of the population belonging to each ethnic group in each country from the Composition of Religious and Ethnic Groups (CREG) project. Secondly, I apply the most commonly used formula (Herfindahl index) capturing the probability that two randomly selected individuals belong to different ethnic groups. I then calculate an ethnic fractionalization index for each year in the period 1945 – 2013 in 165 countries. This way, the dataset allows its users to compare developments in ethnic fractionalization over time. Interested readers may access the new open-access dataset on countries’ historical ethnic fractionalization worldwide at the Harvard Dataverse and the EUI Research Data Repository.

Source: Drazanova, Lenka. (2019) “Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF)”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4JQRCL, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

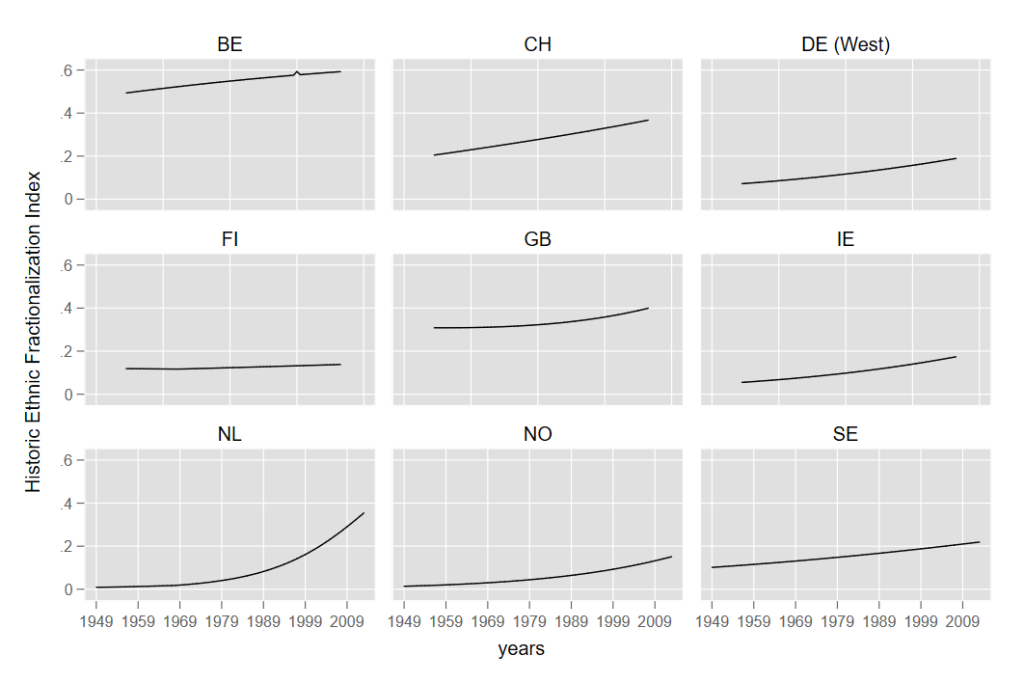

Comparing changes in diversity among European countries

Explorations of the new dataset illustrate the reasons why it is important to take account of historical changes in ethnic diversity within countries. Figure 1 shows the change of ethnic fractionalization over time in a sample of Western European countries. We can observe, for example, that Great Britain and the Netherlands had a similar level of ethnic fractionalization in 2013, but since 1949 diversity in the Netherlands has grown at a much faster pace than in Great Britain. In other words, Dutch society had to adapt to diversity more rapidly than the British. In contrast, we also see that Finland’s ethnic fractionalization was generally low in 2013, and that it has stayed quite stable over the last 50 years.

Source: Drazanova, Lenka. (2019) “Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization Dataset (HIEF)”, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4JQRCL, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

On the other hand, as shown in Figure 2, many Central and East European countries are much more ethnically homogenous than they used to be. Moreover, they became homogeneous in a short period of time. For instance, while former Czechoslovakia used to be a highly ethnically heterogeneous country, its successor states, Czechia and Slovakia, are much more homogeneous. Apart from separations of what used to be ethnically heterogeneous countries such as Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia or the Soviet Union, there are a number of reasons why one can observe changes towards more homogeneity in Central and Eastern Europe. Firstly, after the collapse of communism many workers left their respective countries in search of new economic opportunities. Secondly, in many post-Soviet countries Russian minorities begin to feel unwelcomed, resulting in return migration.

Many studies have concluded that ethnic diversity has a negative impact on economic development, macroeconomic stability, social trust, participation, quality of governance, democracy and many other socio-economic outcomes. However, I argue that there may be value in re-thinking the assumption of ethnic diversity being relatively time-invariant. Changes in heterogeneity might play a role in affecting the relationship between ethnic diversity and socio-economic outcomes. Looking at long-term effects and (rapid or slow) time-variant changes in ethnic diversity can help us to advance knowledge about peaceful co-existence in ethnically diverse societies.

Lenka Dražanová, Research Associate at the Migration Policy Centre (MPC)

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.