Read more

Blog, Linking research, debates, and policies

Research and policy: a troubled relationship?

Research and policy do not always seem to fit very well together. There is a massively increased research interest in migration in Europe and at EU level, but does all this research actually filter...

The Ukrainian political crisis over the EU association agreement stands as the most painful reminder of the unresolved issues that will determine the future of Europe in its geographical borders. Ukrainian society is deeply divided about the country’s future international alignment: while a short majority is in favour of having closer relations with the EU, the other part of the population supports closer links with Russia, instead. The direction that Ukraine will take depends on many factors. Mobility and migration issues between the biggest Eastern European country and the European Union are particularly important in this respect. People-to-people contacts determine cultural and mental affinity, create understanding and help ‘build bridges’. If the EU wants to win the hearts and minds of all Ukrainians and promote its democratic model, it should act boldly and change geographical dynamics, spurring more mobility from Ukraine towards the EU.

So what is the reality of migration and mobility between the EU and Ukraine today and what should be done?

- Ukraine nationals engage more often in migration to the EU and this trend should be reinforced

In general, the mobility of Eastern Partnership nationals has been skewed towards the Russian Federation. This is a consequence of the legal environment that mobility takes place in. First, the visa-free regime in the CIS for short-term visas encourages more temporary/circular mobility in this direction. Second, as in the specific case of Belarusians (and possibly soon Armenians) de facto freedom of movement within the Eurasian Economic Community enhances the migration stream. It not only allows for visa-free mobility but also opens the labour market to potential workers. Third, mobility towards the EU is regulated by visa regime and channels for labour migration are limited, with the exception of Poland and to a lesser extent Italy.

Despite the different legal regimes, the mobility of Ukrainians has been steadily re-directed towards the EU over the last 5 years.

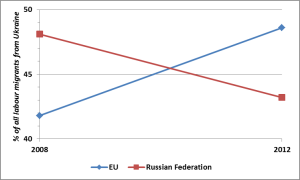

Fig. 1 Ukrainian migrant workers by area of destination in 2008 and 2012 (%)

Source: Nationwide Ukrainian surveys of labour migrants, 2008 and 2012, Ukrainian Statistical Service, Ukrainian Centre for Social Reform and Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.

The data from censuses also reflect this changing trend, showing the diminishing attractiveness of the Russian Federation for Ukrainians.

The change might be in part explained by more relaxed entry policies in countries like Italy, Poland and the Czech Republic. They are in the forefront of the competition for Ukrainian migrants with the Russian Federation and they seem to be winning. This would be the right path for the EU to take.

- Asylum abuse from EaP nationals, in particular from Ukrainians, represent only a limited threat and should not be a limit to migration and mobility

In 2011/2012 there were roughly 300,000 asylum applications submitted to the EU. The most quantitatively significant applications from EaP nationals came from Georgians (over 7,600, 10th place) and Armenians (7,000, 16th place). Yet, two nationalities that rank the highest among migrant workers and visitors to the EU, i.e. Ukrainians and Moldovans, were at the bottom of the asylum application rankings. The fear of asylum abuse from Ukrainians, should they have more gateways for entering the EU, is not grounded: people who do not come from post-conflict areas usually choose gateways other than asylum.

- The EU should develop its attractiveness in the on-going competition with Russia for talents and mid-skilled workers

The global hunt for the highly skilled is now on. Eastern Europeans are overall well educated and as populations have higher level of skills than other, less developed regions of the world. The human capital of the region has been, however, underutilized, not least in the destination countries. Both Russia and the EU have been unable to make proper use of migrant workers. However, in 2010 Russia introduced a special policy to attract highly-skilled workers, offering important facilitations and incentives. There is no similar programme at the EU level and national-level initiatives are scarce: the UK, Sweden and Denmark being, to some extent, exceptions.

At the same time it is becoming increasingly clear that the EU will need predominantly mid- and low-skilled migrants for its labour market. The Russian Federation is, for now, much more successful at attracting such workers from Eastern Europe.

The competition for Eastern European migrants, including Ukrainians, is thus ongoing and has entered a new phase. The EU should develop new approaches to take full advantage of its growing attractiveness.

Further reading:

The interested reader can also consult the Regional Migration Report: Eastern Europe.

Anna di Bartolomeo, Research Assistant to CARIM East, CARIM India and CARIM South.

Agnieszka Weinar, Scientific coordinator of CARIM-East and INTERACT.

—

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.