Read more

Blog, Migration Governance

The Second COVID-19 Wave in Nepal and Nepali Migrants

As detailed in a blog post “COVID-19 and Reverse Migration in Nepal” from last June, there was much uncertainty about the impact of COVID-19 on Nepal’s migrants amid the health risks, lockdown and flight...

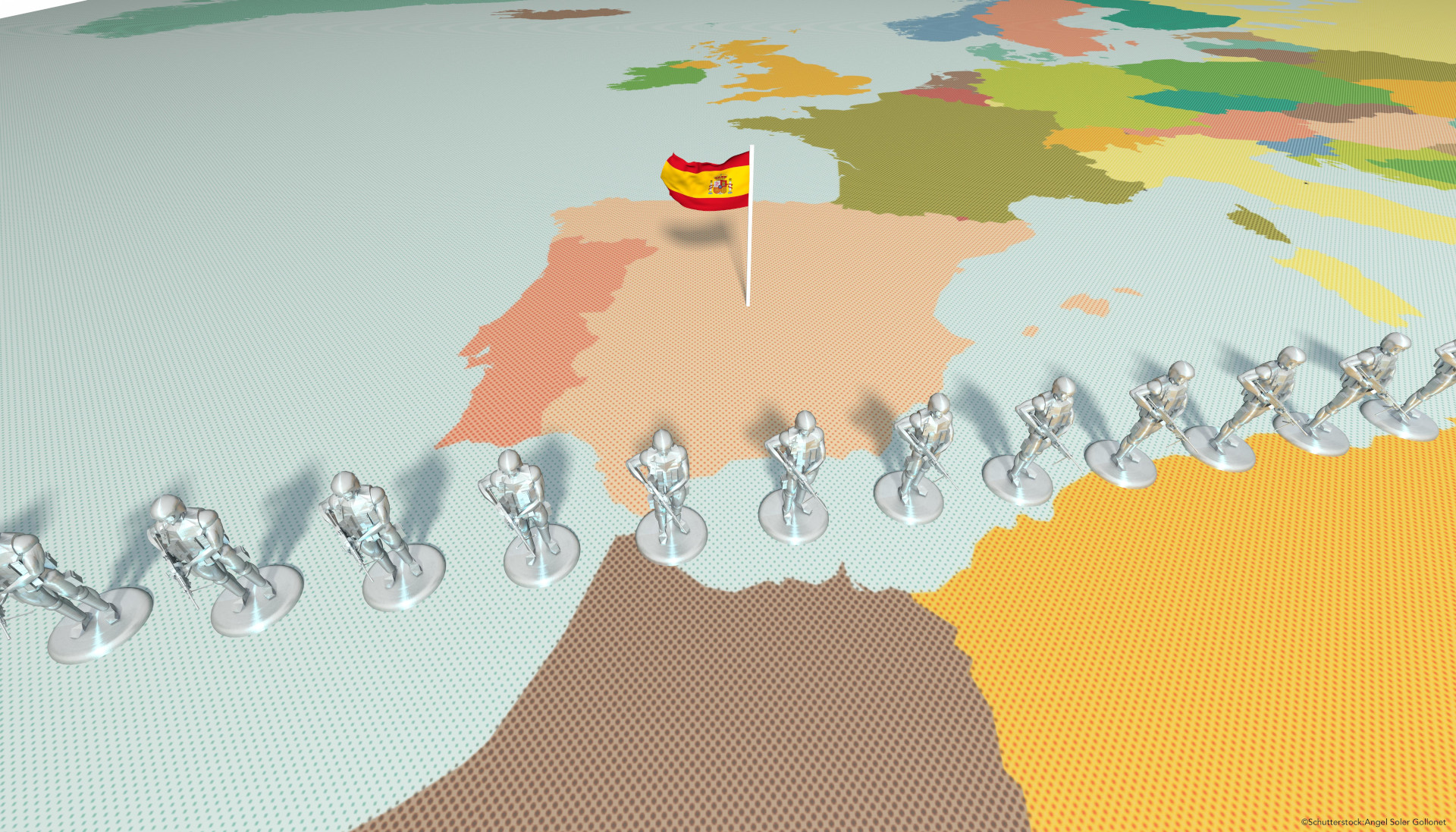

While there are clear power asymmetries in African-European migration relations, African countries sometimes use migration and migrants as a counterbalance to European strength. This counter-balancing was evident on May 18 2021 when Morocco recalled its ambassador to Spain in the midst of a dispute caused by 8000 migrants leaving Morocco to enter the Spanish enclave of Ceuta. The crossing was reportedly Morocco’s response to Spain’s decision to admit for medical treatment Brahim Ghali, the leader of the Western Sahrawi Arab Republic and its independence movement.

The Morocco-Spain dispute exposed wider financial and diplomatic power asymmetries between Europe and Africa that have distorted African priorities. The asymmetries further created pressure to implement policies that privilege European interests over those of African countries and migrants. The result is that migration and migrants can be weaponized as a diplomatic tool.

Morocco’s prominence in migration diplomacy is not only about the numbers of migrants originating from and transiting through it, but also about its geographic proximity and foreign policy that promotes active engagement on migration issues. The diplomatic row between Morocco and Spain occurred in the context of other ongoing bilateral negotiations between the EU, Tunisia and Libya.

All provide good examples of how geographic factors inform, influence, and shape African policy-making, where migration is used as a diplomatic and foreign policy tool to promote a country’s global standing and pursue national interests in regional and international relations.

There are, however, other factors that determine the policy decisions of African countries. The EU footprint on migration issues is extensive, particularly in Africa, and can be attributed to the European Union Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). Signed by 25 EU Member States plus Norway and Switzerland, and launched by the European and African partners at the Valletta Summit on Migration in November 2015, the EUTF amounts to €5 billion, and supports 204 projects in 26 African countries.

The EU also released other funds related to African migration management before 2015 including: the European Development Fund (€30.5 billion); Internal Security Fund focused on borders and visas (Eur €3.6 billion); Return Fund (Eur €676 million); and External Borders Fund (€1.8 billion). These projects are supported by more than 63 agreements and memoranda of understanding, including the Migration Partnership Framework.

In a bid to intensify migration diplomacy, a Contact Group was established for the Central Mediterranean route. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX), EU Border Assistance Missions, the G5 Sahel Joint Force and EU migration officers have moved their assets and are operating on the ground in Africa. FRONTEX has moved its areas of operation deep into Africa. Europe’s cooperation on migration with Africa has led to competition among branches of local governments to work with the EU and FRONTEX in order to access financial and diplomatic support for their respective institutions.

Since the Valletta Declaration, many African countries have negotiated with the EU, and bilaterally with European countries, the World Bank, IOM, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The result is that several African countries have revised their laws related to refugees and the trafficking of persons, smuggling of migrants and labour migration, and have aligned them with pledges made under the Valletta Declaration, the New York UN Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework, and bilateral agreements with the EU and its Member States.

While these migration agreements (both bilateral and multilateral) focus on the operational dimension of migration, the Europe-Africa partnership extends to norm-setting and norm-diffusion. Partially attributable to these partnerships, more than 39 African countries have developed or are in the process of adopting policies, strategies, migration profiles and action plans, with particular emphasis on countering irregular migration, trafficking in human beings and people smuggling. To implement these agreements, many African countries have ramped up their prosecution and sentencing of traffickers and smugglers.

To understand the balance between interests, rights and values in African migration governance it is necessary to focus on the determinants of African migration policy-making. Seven key and mutually reinforcing factors influence, inform and shape African migration policy-making with regard to partnership with Europe.

- Migration and development: two sides of a coin

The first and most pervasive factor relates to the view that African policy-makers see migration and development as two sides of the same coin: one cannot be addressed without the other. Despite some research suggesting otherwise, for African governments, addressing irregular migration, including trafficking and smuggling, requires measures to tackle extreme poverty. Seen as the prime cause of African youth migrating without proper documentation along dangerous and sometimes even fatal routes that involve illegal crossing of borders, African policy makers assert that development constitutes a crucial component of effective migration governance.

- Regime type

The second determinant of policy decisions and levels of cooperation on migration is the regime type with variation in democracy, transparency and accountability. As in other areas of public decision-making, migration policy is calculated against the costs or benefits associated with constituency-based domestic politics and the financial gains to be made from cooperation. Such cost-benefit calculation largely depends on the regime type and how it responds to political pressure and diplomatic risks.

In democratic countries, governments face stiffer challenges if decisions on migration are considered to violate international human rights law. Constitutional democratic institutions and constituency pressure keep government actions in check. Lacking such constitutional and electoral accountability mechanisms, less democratic regimes rarely face accountability and pressure for their decisions on migration, including return.

Accountability and responsiveness to demands from the public, media and other stakeholders can all affect the degree of cooperation and policy implementation. Regime type also influences how authorities calculate domestic risks, the human rights violations migrants may face, and the responsiveness of government to pressure from countries of transit or destination.

The nature of the countries of destination from where migrants return (democratic or authoritarian, economically developed or not) impact decision-making on the African side. This is why some migration routes are more important for partners than others. For example, East Mediterranean routes attract much political attention, media coverage and resource allocation, despite the enormity, gravity and implications of other more critical routes. Diplomatic pressure and legal accountability work more effectively in European destination countries with established democracies and strict rule of law than in Middle Eastern countries with less transparency, and less legal and political accountability.

- Aid and remittances

Related to the second factor, and perhaps the most forceful incentive in migration policy-making are aid and remittances.

Many African policy-makers would prioritise any agreement that might alleviate foreign currency shortages, as these, together with the associated inflation and high youth unemployment, can push governments to the brink of collapse. Aid transfers and remittances can serve as a stable source of foreign currency and development finance. Access to finance and hard currency play a critical role in the formulation of African migration policies. Thus, European migration diplomacy significantly influences policy-making processes in African origin or transit countries on migration routes to Europe.

- Diplomacy and geographic proximity

Colonial, historical, social, geographic, religious, and family relations make for special ties between African origin and European destination countries. Migrant culture and diaspora networks impact the routes, trends and frequencies of migration, and profoundly shape migration policy-making processes in Africa. European countries with such relationships have more leverage in influencing and informing the decisions of African policy-makers than those without.

- Capacity to control borders

Fifth, a genuine concern for African states when making migration policy is the limitations on their capacity to govern – or, more narrowly defined, control – borders. In general, many African states lack the resources necessary to effectively govern migration on the continent.

- Lobbying, advocacy and fraudulent practices

Sixth, advocacy, lobbying, and fraudulent practices play a part in shaping policy decisions and implementation related to migration, particularly at local and border areas. Labour migration agencies, brokers, smugglers, traffickers, hospitality and transportation businesses often have close links with government officials, including members of parliament and ministers in charge of migration-related decision-making, particularly at a local level. Lobbyists and other business owners frequently develop close relations with ministers, parliamentarians, city mayors, border officials and other government officials, and are therefore able to influence migration policy-making.

- Pan-African integration agenda

The Pan-African integration agenda, such as the establishment of free movement regimes and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), shapes national migration policies. The free movement regime and the AfCFTA offer an overlapping area of interest for cooperation with Europe. As initiatives that are legally binding, and which constitute a long-standing Pan-African aspiration, free movement regimes and the AfCFTA could prove more effective than previous attempts to implement partnerships on migration with Europe.

Despite signing the EU Common Agenda on Migration and Mobility, African countries have backpedaled on their pledges, due to likely negative political repercussions and consequent instability in their constituencies. Facing the dilemma between demanding respect for fundamental human rights on the one hand, and seeking an end to the outflow of migrants on the other, Europe has had active relations with such regimes on migration partnership. In the long term, the balancing act needs to tilt away from narrow conceptions of interests towards human rights and values.

Mehari Taddele Maru, Migration Policy Centre (EUI)

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.