Read more

Blog, Public Attitudes

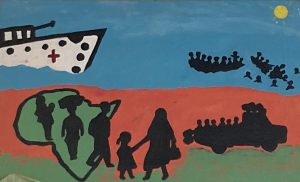

Convinced to Stay? The Impact of EU-Funded Information Campaigns in West Africa

The EU is trying to discourage Africans from travelling irregularly to Europe, but can they be persuaded to stay in African countries? This blog post shows how an EU-funded narrative is perceived by West...

Over 5.5 million people have fled Ukraine since Russia’s invasion on 24 February. Amid the fastest and largest displacement in Europe since World War II, the EU has mostly been united in its support of Ukrainians – as evidenced by the first-ever activation of the two-decade-old Temporary Protection Directive. Triggered just over one week into the war, this Directive, and the visa-free regime, allow Ukrainians to choose in which Member State they would like to settle, enabling them to join up with their networks, make use of their language skills, or follow job opportunities.

But the groundswell of solidarity reaches beyond the EU+: Several countries farther afield have made new or existing migration channels available.

Who is doing what?

Argentina has authorised the entry and stay of Ukrainian nationals and their immediate family without immigration fees. The same provision grants temporary protection status for up to 3 years, after which beneficiaries can apply for permanent residence. The country has also discussed with UNHCR the possibility of resettlement and other channels.

Ukrainian citizens wishing to enter Australia can apply for one of several visas. After obtaining a visa for temporary humanitarian stay, Ukrainians can apply for a Temporary Humanitarian Concern visa. This three-year visa allows work and study in Australia and access to Medicare, free English classes, and other services. Visa holders can request support services from the Humanitarian Settlement Program. As of 6 April, over 1,700 Ukrainian nationals have arrived.

Brazil is granting humanitarian visas to Ukrainians. Following an initial stay of 180 days, visa holders are entitled to temporary residency for 2 years, after which they can apply for a permanent visa. Ukrainians travelling to Brazil without a visa can apply for a residence permit in country. In March, 74 visas and 27 humanitarian residence permits were granted.

In Canada, the Authorization for Emergency Travel enables all Ukrainian nationals and their immediate family members to enter the country with minimal visa requirements for a 3-year stay (renewable). Applicants are encouraged to simultaneously apply for an open work permit, enabling them to work for any Canadian employer. Visas and work permits are provided free of charge. Canada later announced that Ukrainians will have access to federal support from the Settlement Program, typically limited to permanent residents, for one year. There is no cap on the number who can apply. Signalling high interest, 163,747 people have submitted applications for emergency travel; 56,633 applications have been approved (17 March – 19 April 2022). In addition to this temporary pathway, Canada is prioritizing family reunification applications for immediate family members, and will set up a sponsorship programme enabling extended family to follow, offering pathways to permanent residence. Other immigration opportunities are also possible. All in all, 19,628 have arrived/returned (1 January – 17 April 2022).

Israel launched the ‘Aliyah Express’ programme to fast track the arrival of Ukrainians of Jewish descent, who can travel before being certified as eligible. After setting a quota of 5,000 non-Jewish Ukrainians, Israel announced that there will be no cap for Ukrainians with family members in the country. An estimated 18,000 Ukrainians had arrived in Israel by the end of March, one-third of whom are Jewish.

New Zealand’s 2022 Special Ukraine Policy, open for one year, allows citizens/residents born in Ukraine to sponsor immediate (and certain extended) family members. Sponsored relatives will be given a two-year visa enabling them to work (or attend school), potentially allowing entry for approximately 4,000 Ukrainians. Sponsors must bear the travel, accommodation, and living costs.

The UK created two channels through which Ukrainian citizens and their immediate family members can apply for a visa. Those with (immediate or extended) relatives already in the UK can apply for the Family Scheme for a stay of up to 3 years. Application is free and passports are not required. The Sponsorship Scheme (also called ‘Homes for Ukraine’) was established for those without relatives in the UK. Sponsors can name the person they wish to sponsor or register their interest if they do not know anyone personally; they are responsible for providing accommodation and can receive £350 per month for up to 1 year to defray associated costs. Beneficiaries of both schemes are able to reside, work, and study in the UK for up to 3 years and access public funds. There is no cap on the number who can arrive via the Sponsorship Scheme. By 27 April, 27,100 Ukrainians had arrived via these two schemes (117,600 applications submitted and 86,100 visas issued, as of 25 April).

Following the US’ pledge to accept up to 100,000 people fleeing Ukraine using a combination of legal pathways, it launched the Uniting for Ukraine humanitarian parole programme. This complements other legal migration channels, including the Refugee Admissions Program and visas. Starting 25 April, Ukrainians with a US sponsor who meet security and public health requirements can apply for parole to remain for up to 2 years with work authorisation. Resettlement of certain religious minority refugees will also increase under the Lautenberg Program, and of others through its Refugee Admissions Program.

An outsized impact?

These initiatives vary in important ways, notably in whether they offer a path to permanent residency or are open to Ukrainians without family in country. And a key challenge now is to put these pathways into practice. Some schemes have been criticised for being slow and overly bureaucratic and for not sufficiently including non-Ukrainians fleeing the war. Meanwhile, safeguards are essential to ensure that sponsorship programmes provide protection for beneficiaries and do not put them at risk. It remains to be seen how many people will make use of these pathways: Most are expected to want to remain in Europe, to be closer to Ukraine and their families, and in the hope that the conflict will soon end.

The global response to displacement from Ukraine is remarkable in several ways, not least in its speed and scope. The immediate right to work and access key services is similarly noteworthy, as is the fact that many of these pathways rely on family and diaspora members (Ukraine has a sizable global diaspora) and broader public support. Empirical findings from the EU-funded Transnational Figurations of Displacement (TRAFIG) project illustrate that networks help facilitate mobility and integration, meaning that building and leveraging networks can help expand solutions for the displaced.

While there has been increasing momentum behind community/private sponsorship and other complementary pathways, the war in Ukraine has clearly provided further impetus for these approaches. These actions prove that governments can take creative approaches to welcome (many) more displaced people and leverage support among their populations, marking an important step towards greater global responsibility sharing and serving as inspiration for enhanced third-country solutions in other refugee situations.

Caitlin Katsiaficas is a Policy Analyst at the International Centre for Migration Policy Development. Prior to joining ICMPD, she held positions at the Migration Policy Institute, World Bank, International Rescue Committee, and George Washington University’s Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, in addition to internships with local and national refugee resettlement organisations in the United States.