Read more

Blog, Rights, protection and inclusion

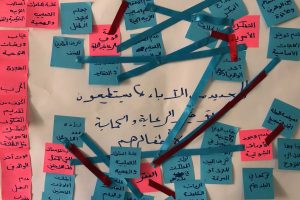

Re-thinking Migration Studies? Developing social research training with refugee communities in Jordan

While calls to re-think, de-centre and de-colonise migration studies has started to trend, what does this mean in practical terms? This blog reflects on our experiences of developing social research training and working with...

The European Union (EU) and its Member States (MS) are heavily reliant on Private Military and Security Companies (PMSC) to enforce their migration policies. PMSCs, for example, are involved in the management of offshore detention centres and in the implementation of forced returns. In this blogpost, I show that the absence of legally binding international and European regulation of PMSCs has contributed to a lack of transparency surrounding EU contracts with PMSCs and accountability in instances of human rights violations.

What are PMSCs?

PMSCs provide migration management services such as drone surveillance and the collection of biometric data. European PMSCs such as Thales and Leonardo represent a sector of major financial significance to the EU, with a turnover of €97.3 billion in 2014. Moreover, certain Member States are significant shareholders within these companies. For example, in 2019 the Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance owned 30% of Leonardo shares, while TSA, a holding company owned by the French states, owned 25% of Thales shares.

PMSCs actively participate in the making of migration and border policies. For example, within Horizon 2020, an EU funded research and innovation programme, the private for-profit sector was the second biggest sector to receive funding from the EU (28%) in the period 2014 to 2020. Within that sector, seven out of the top ten participants to receive funding were members of the European Organisation for Security (EOS), a lobby group with several defence and security companies. Additionally, a report published in 2021 by the left of the European Parliament (GUE/NGL) underscored, among other things, that there exists a strong revolving door between the security industry and the EU. For example, Thierry Breton who is the current Commissioner for the Internal Market and is responsible for the implementation of the European Defence Fund and the Action Plan on Military Mobility was previously the head of Thales. It is difficult to assess the extent to which PMSCs influence policies, but these developments point to a deep enmeshment between EU institutions and this industry.

The need for PMSCs’ technology and expertise extends to policies through which the EU collaborates with non-EU states in the control and management of migratory flows. For example, in 2014, Selex Sistemi Integrati S.p.A was involved in a border security deal with Libya funded by the EU and Italy, which included the supply of advanced border control systems such as satellite-based systems for monitoring the whole cost of Libya.

The absence of regulations and transparency surrounding PMSCs

Reports have recently emerged about the EU placing sanctions on a Russian PMSC working with various African Leaders who have allegedly committed human rights abuses. Other PMSCs have themselves been accused of human rights abuses in the activities that they have carried out on behalf of the EU. While there exists weak self-regulation within the industry such as International Code of Conduct for Private Security Service Providers (ICOC), the UN Working Group on the use of Mercenaries underscores that ‘the most effective way to regulate private military and security companies is through an international legally binding instrument’.

The current lack of transparency and regulation is facilitated by the absence of public awareness surrounding EU contracts with PMSCs, which makes it difficult to hold PMSCs accountable in instances of human rights violations.

Why do agreements with PMSCs matter?

The EU and its member states have become dependent on PMSCs for various aspects of border management and have relied extensively on expertise coming from these private actors. The UN Working Group notes that ‘through this expertise, these companies frame the response to migration as one necessarily characterised by emergencies, crises and perceived threats, feeding and reinforcing the exclusionary, hard-line immigration narratives’ and ‘push for security and often militarised solutions’. PMSCs have a strong incentive to push for hard-line immigration policies to make a profit. Turning a migrant into a security threat carries the risk that the EU’s obligation to refugees will be overridden, as it happens with illegal pushbacks.

The lack of transparency in the EU agreements with PMSCs makes it difficult to assign responsibility for human rights protection and duty of care. A recent collection of academic writings on the privatisation of security shows that much like the underlying logic of the EU’s externalisation of borders, the delegation of authority to private actors allows states to obfuscate such responsibilities. The lack of regulation on PMSCs and the difficulty in determining the content of due diligence obligations makes it difficult to establish whom to hold accountable if human rights abuses occur and how to do it. This is accompanied by a lack of transparency with regards to how data is gathered and shared by PMSCs. The blurring of responsibility is accompanied by an even more pernicious effect: the normalisation of the use of PMSCs to regulate migration.

What can be done?

Despite the strong entanglement between PMSCs and EU border policy, there remains little public scrutiny of this relationship. The European Parliament, for example, continues to be side-lined in its efforts to achieve greater transparency. Falling short of stronger political checks, civil society plays an important role. Specifically, open-source information helps documenting human rights violations and enhancing public scrutiny over the contractual relationships between the EU and PMSCs.

Micol Sagal Ambroso is a master’s candidate in International Relations and Political Science at The Graduate Institute Geneva and an exchange student at the School of Transnational Governance of the European University Institute. Her interests are in conflict, conflict resolution and peacebuilding as well as the role of private military and security companies in these areas and within the area of migration. She is currently working on her dissertation focusing on the climate-security nexus in the Sahel. This blogpost is part of our forum on the transnational governance of migration. The views and opinions expressed in this post are the author’s own.