-

Mehari Taddele Maru

Part-time Professor

School of Transnational Governance

Read more

Blog, Labour markets & welfare states

Supporting Migrant-Owned Businesses in Europe: A Quadrumvirate Approach

On the surface, a wide range of organizations and institutions are in favour of promoting migrant businesses. Cities, regions, countries, the European Commission, and corporations all agree that migrant-owned business help the inclusion of...

In mid-April, fighting erupted in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). As of 18 June 2023, the conflict has resulted in over 1,000 civilians deaths and left 2.2 million people displaced; of 78% whom are Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). Thisraises the total number of IDPs in Sudan to over 5.5 million.

The fighting, sparked by a power struggle between military leader commanders Lt Gen Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of the SAF and RSF commander Lt Gen Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, has turned into a war for survival. The causes, and the consequences of this war extend beyond the generals themselves. The resolution of this war requires more, not just the generals’ will, but also multi-stakeholder efforts, including extra-national approaches, which transcends the battlefields. The outcome will most likely determine the future political landscape of Sudan, particularly in how it impacts on the precarious, drawn-out centre-periphery relations, but also in how it shapes the transition to a constitutional democracy. It will also affect the central government’s relations with extra-national forces, including neighbouring countries, particularly Egypt, Chad, South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, the Central African Republic (CAR), and Libya.

This post discusses how Sudan’s ongoing conflict and displacement arise from a mix of factors, mainly poorly managed political transitions, an unwillingness to commit to ending hostilities, tumultuous centre-peripery relations, and unwarranted extranational geopolitical interferences. Solutions to the most of the displacement could be found in Sudan’s transition to a constitutional democracy, effective conflict prevention, and a move to address power imbalances that are exacerbated by both regional and extra-regional forces.

Displacement within Sudan

To date, the war has displaced 1.6 million people in 17 of Sudan’s 18 states. Before the fighting erupted, roughly 83% of IDPs in Sudan were primarily located in Darfur, a region that has been besieged in genocidal conflict since 2003. The power imbalance between central regions such as Khartoum and peripheral areas such as Darfur significantly influences not only previous and ongoing conflicts in Sudan but also the level of displacement. Although Khartoum is the primary site of the most recent conflict, peripheral regions and border areas such as Darfur have been the principal theatres of the previous atrocious war. Theyhave also borne the brunt of the current war and displacement, serving both as the origin and refuge for most IDPs and refugees. This has resulted in disproportionate suffering and displacement in these peripheral regions, further deepening existing tensions. Now as the conflict moves toward the peripheries, Darfur finds itself in an ensuing battle seemingly set on wiping out the vestiges of the 2003 genocidal war and displacing even more.

The crisis has also affected foreign nationals, who constitute approximately 11% of Sudan’s IDPs, including refugees who escaped the wars in South Sudan and Ethiopia and compulsory and indefinite military service in Eritrea.

Overview: Impact of Displacement within Sudan

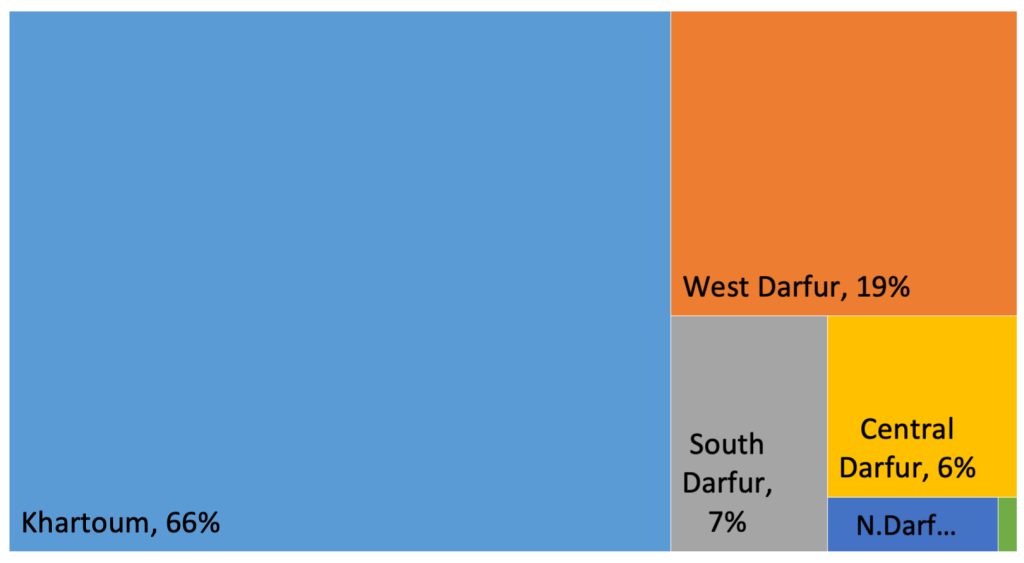

- Where Sudanese have been displaced from: A significant majority (72%) of people have been displaced from Khartoum state, followed by West Darfur (19%), South Darfur (6%), North Darfur (2%), North Kordofan (1%), and Central Darfur (<1%) as the origin for large number of IDPs.

- Where IDPs are being hosted: the West Darfur (24%), White Nile (20%), River Nile (16%), and Northern states (13%) host the highest figures of IDPs.

- Cities most affected: Cities affected include Khartoum, Al Fasher, Merowe, Nyala, Ag Geneina, Salingi and El Obeid. Six states account for the majority of IDPs, specifically Khartoum, West Darfur, South Darfur, North Darfur, Central Darfur, and North Kordofan.

Origins of Displacement for Sudanese IDPs / % of Total IDPs in Sudan

Source: Compiled by Author, Data from DTM IOM-Sudan; As of 4 June 2023. Dark blue represents North Darfur (2%); Green represents North Khartoum (less than 1%).

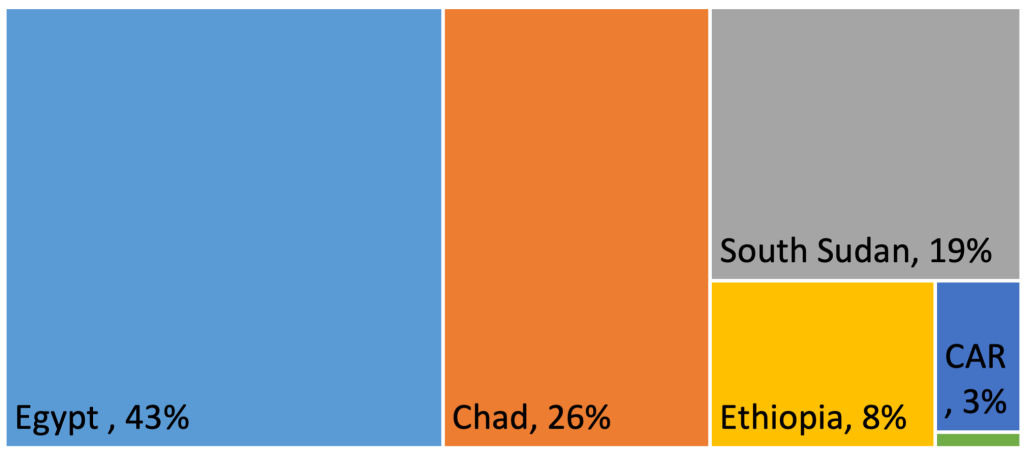

External displacement to neighbouring countries

The war in Sudan has forced 477K individuals to seek protection in, or to transit through neighbouring countries. Around 60% of those fleeing across the borders are Sudanese nationals, while the other 40% include South Sudanese, Nigerians and Ethiopians and refugees of other nationalities who previously fled their own countries and were being hosted as refugees in Sudan. Most of these refugees and asylum seekers (43%) have sought refuge in Egypt. Chad is hosting 26% of the displaced, with 19% crossing the border into South Sudan. Of the remaining 12% of refugees and asylum seekers, approximately 8% have sought safety in Ethiopia, 3% in the CAR, and less than 1% in Libya.

Percentage of Refugees Fleeing Sudan Received by Neighboring Countries between 1 April- 4 June 2023

Source: Compiled by Author, Data from DTM IOM-Sudan, as of 4 June 2023. Green represents Libya (less than 1%).

Dynamics of displacement

The ongoing conflict in Sudan, exacerbated by this widespread displacement, is having a significant impact on neighbouring countries, particularly Chad, South Sudan, Eritrea, Egypt, Ethiopia, the CAR, and Libya. Already grappling with their own poly-crises (the simultaneous occurrence of several catastrophic events), these countries are under added strain owing to the sizeable influx of Sudanese refugees and refugees of other nationalities who had been hosted by Sudan. Libya and Sudan are mainly known as transit routes for mixed migration from Eritrea and Ethiopia. In these border regions, numerous smuggling and trafficking networks have been thriving, in many cases supported by local officials and armed factions. Because to the wars in Sudan and Libya, state institutions are inefficacious or virtually absent in these border areas, resulting in limited governmental purview and a consequent surge in mixed cross border migration heading towards Libya and other neighbouring countries. A concerned European Union hasrapidly deployed humanitarian experts to manage border crossing points between Sudan and its neighbours.

Given that Sudan borders the Tigray region of Ethiopia, the site of the world’s current deadliest war since the Rwandan genocide against Tutsi in 1994, many Tigrayan refugees fleeing the war have sought sanctuary in Sudan, fearing potential ethnic cleansing if they were to return to Ethiopia. Likewise, Eritreans face persecution and military conscription if they return to their homeland. With no viable options for return, these individuals find themselves trapped in Sudan amidst escalating violence. Desperate for a way out, they are vulnerable to human traffickers and smugglers who deceitfully promise them a safe passage to Europe or other destinations. Many refugees are kidnapped and trafficked north towards Libya’s border from refugee camps in Sudan that aremanaged by the UN and the Sudanese government,.

Patterns of displacement

The complexities of displacement and refugee issues in Sudan and its neighbouring countries are marked by specific dynamics and patterns.

Proximity and historical ties

Many Sudanese nationals flee to neighbouring countries such as Egypt and Chad due to their closeness, historical links, safety, existing migration routes, and family ties. These displacement patterns are also influenced by the availability of transport, history of previous travels, and the presence of family members and kin communities in these countries.

Strained resources in host countries

Countries with significant refugee populations, such as Chad, Egypt, South Sudan, and Ethiopia, now face an additional influx of asylum seekers. The rapid increase in refugee numbers places significant strain on these countries’ resources and challenges the capacity of international humanitarian responses.

Locations hosting more IDPs and refugees

Sudan has long been a refuge for people fleeing conflict, violence, and persecution in neighbouring African and Middle Eastern countries such as South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, the CAR, Chad, Syria, and Yemen. A significant number of asylum seekers in Sudan live outside of formal camps. Certain areas of Sudan, particularly Khartoum and the Darfur states, have a history of both hosting and producing IDPs and refugees. Violent conflicts, especially in Darfur and Kordofan, and natural disasters such as flooding, have contributed to significant internal displacement.

Spontaneous returns of refugees

The dynamic of foreign nationals, including refugees in Sudan (mainly South Sudanese), returning to their home countries, is also an essential part of the displacement scenario. Most of those returnees are from South Sudan and Ethiopia. Various countries, such as the United States, Canada, Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, France, Kenya and South Africa, have evacuated their nationals by air and through neighbouring countries, particularly Egypt.

Outlook: More IDPs and refugees

The emerging data presents a compelling narrative of an alarming and large-scale displacement crisis in Sudan. The UN Refugee Agency’s(UNHCR) Supplementary Appeal for the Sudan Emergency spanning May to October 2023,) projected an additional influx of 1.2 million IDPs and 129,000 refugees who may experience secondary displacement. These calculations were made to shape the response to the intensifying crisis in Sudan during the aforementioned period.

To deal with this emergency alone, the UNHCR needs $253.9 million. This is in addition to the funds required for related operations, which have already reached a staggering $1.421 billion in 2023. Meanwhile, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) is preparing to assist 8,000 of an estimated 30,000 third-country nationals affected by the crisis. However, in a little over a month following this projection, the number of displaced persons has alarmingly exceeded initial expectations, surging to an overwhelming 2 million. This stark increase underscores the deepening gravity of the crisis, highlighting the urgent need for an intensified response from both international aid organizations and the global community. The escalating situation underlines the substantial humanitarian challenge that lies ahead, further emphasizing the urgency to rally resources and amplify relief efforts.

Sudan’s IDPs face numerous challenges, and several factors should be considered when devising strategies to alleviate their predicament. These factors include:

- Protection against physical attacks: IDPs require safeguarding from physical harm. This calls for a competent security framework capable of diminishing threats and protecting vulnerable populations.

- Relationship with host communities: A good rapport between IDPs and host communities is crucial. Promoting harmonious relationships can facilitate the integration of IDPs, thereby expediting their protection and assistance.

- Durable solutions: It is crucial to reinstate the ability of IDPs to earn a living and reconstruct their lives. These solutions must be guided by human rights norms, respect freedom of movement, and provide protection against forced return and discrimination.

- Socio-economic development and governance: Effective responses to displacement crises are closely linked to socio-economic development and effective and inclusive transitional governance. Building resilient economies and governance structures can help decrease the susceptibility of communities to displacement. A comprehensive approach, incorporating legislative, policy and practical measures, is crucial. This approach should foster human security, including socio-economic development and conflict prevention.

- Climate change adaptation and prediction: As climate change increasingly triggers displacement, it is imperative to strengthen the predictive, preventive, responsive and adapative capabilities in Sudan’s most vulnerable areas. This involves crafting adaptive responses, including early warning systems for conflict, drought, famine, and natural disasters. Such measures can bridge the gap between scientific early warning and political decisions necessary for early preventive response by national, and international community.

Getting transitional governance right

The recent agreements on humanitarian truce in Sudan are a much-needed respite to the intense fighting that has been ongoing for months. However, it is evident from the troubled history of the Horn of Africa that political transitions must be carefully planned and executed to prevent them from causing further instability, social unrest, wars, deaths, displacement, and destruction.

Political factors are primarily responsible for the massive and protracted displacement in Sudan, and the remedy lies in reaching a Sudanese political settlement and instituting effective and legitimate governance. Arriving at this outcome will require a leadership committed to ceasing all hostilities, resolving political differences peacefully, and establishing an inclusive civilian transitional authority. Dealing with the issues faced by IDPs and refugees requires a holistic and multifaceted global approach that addresses both the root causes and symptoms of displacement. This strategy should encompass enhancing governance, ensuring physical security, advocating for human rights, adapting to climate change, and fostering positive relationships between IDPs and host communities.

–Mehari Taddele Maru

European University Institute, @DrMehari