-

Leila Hadj Abdou

Part-time Assistant Professor

Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

Read more

Blog, Mobility Practices and Processes

Borders of rich and poor countries have abundant cross-border traffic infrastructure, new global dataset reveals

A new global dataset on cross-border roads, paths, railroads, and ferries reveals that borders of very rich and very poor countries have ample cross-border traffic infrastructure, much more so than middle-income countries. Why is...

In many ways, a lot has changed in migration policy in the European Union in the past few decades. There were far reaching institutional changes that resulted from the Lisbon Treaty and an expansive shift to multi-level, and cross-sectorial governance. These changes brought in a diverse set of (private and public) actors and ideas into this policy field. Despite these developments, as well as several ‘migration crises’ that could have worked as a game changer, the fundamental migration policy course in the EU has remained the same– focused on deterrence and combatting irregular migration.

How can we understand this tendency for things to remain “status quo”? To address this question, in a recent article in the Journal of European Public Policy, we looked at a largely neglected aspect in migration research: the policy environment in which migration policy actors form their understanding of policy problems and make choices.

What is this “status quo tendency” about?

Nearly a decade ago in 2013 more than 300 migrants died at Europe’s shores near the Italian island of Lampedusa. At the time, the then EU Commissioner for Home Affairs Cecilia Malmström underlined that this tragedy must be a wake-up call for the EU and its member states to change their policy course in the field of migration. She called for action at the European level, and the opening of more channels for legal migration:

“In the longer term we need a more open approach to migration, to define a common European policy based on the rights of the migrants and of the asylum seekers and on solidarity to both the migrants and the member states (European Commission, 2013).”

Ten years and several migration crises later, the policy vision outlined by Malmström is even more untenable than it was at the time. Instead of the policies changes called for by the Commissioner, we have seen more of the same in the past years:

- Solidarity is still in high demand, but rare to find.

- Humanitarian tragedies, such as the rising death toll in the Mediterranean, have paradoxically seemed to reinforce and consolidate the deterrence approach.

- “Fighting irregular migration” and reducing asylum-seeking migration have remained consistently the key components of EU action.

- Legal migration pathways have remained the weakest component of EU policy.

- Efforts to relocate asylum seekers across member states have largely failed and have been quasi abandoned.

As immigration has become hyper-politicized, securitized, and used for electoral mobilization by political parties, these deterrence approaches seem to have become the new (and unquestioned) normal, even though, paradoxically, there is ample research evidence that deterrence-based approaches can backfire and lead to an increase in migration stocks and asylum seeking flows.

Certainly Europe’s response to the ongoing displacement of Ukrainians in the wake of the Russian invasion has been remarkably different from those to previous migration “crises”. The EU and its member states have for the first time used the Temporary Protection Directive (2001/55/EC), which has granted those fleeing Ukraine with immediate protection and access to the labour market. Overall, however, these recent developments are limited to a specific group of individuals displaced from Ukraine, and have therefore not affected the “status quo” in the field of migration or altered the overall policy course from its focus on deterring asylum seekers and other “unwanted” migration.

Why is this puzzling?

At least two factors make this absence of fundamental policy change in EU migration policy puzzling. First, the migration field in the last decade has been characterised by powerful and persistent ‘crises’, which have been perceived not only as crises for the member states but as a crisis of the EU and its governance. Crises tend to produce uncertainty, and in doing so can stimulate new policy solutions, or can at least provide a powerful window of opportunity for change, as the statement by Malmström cited above underlines.

Second, the diversification of actors in the migration policy field from the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 onwards might have also potentially led to some change of policy course. The Lisbon treaty granted the European Parliament co-decision powers on EU migration matters. What is even more relevant, migration is today understood by most European governments and the EU itself as a cross-cutting policy issue. New government actors with a more “liberal” migration agenda, such as ministries of Foreign Relations, Labour, Development and Trade, became more involved in the field of migration. Moreover, third countries, international organizations, think tanks, NGOs, and private companies, have also been increasingly involved in migration policymaking and implementation. These developments predate the 2015 migration crisis, but the crisis further expanded the number of migration policy actors, and made calls for alternative (typically more protection-oriented) policy approaches that were advanced by some of these actors more prominent.

How can we fully understand this lack of fundamental policy change?

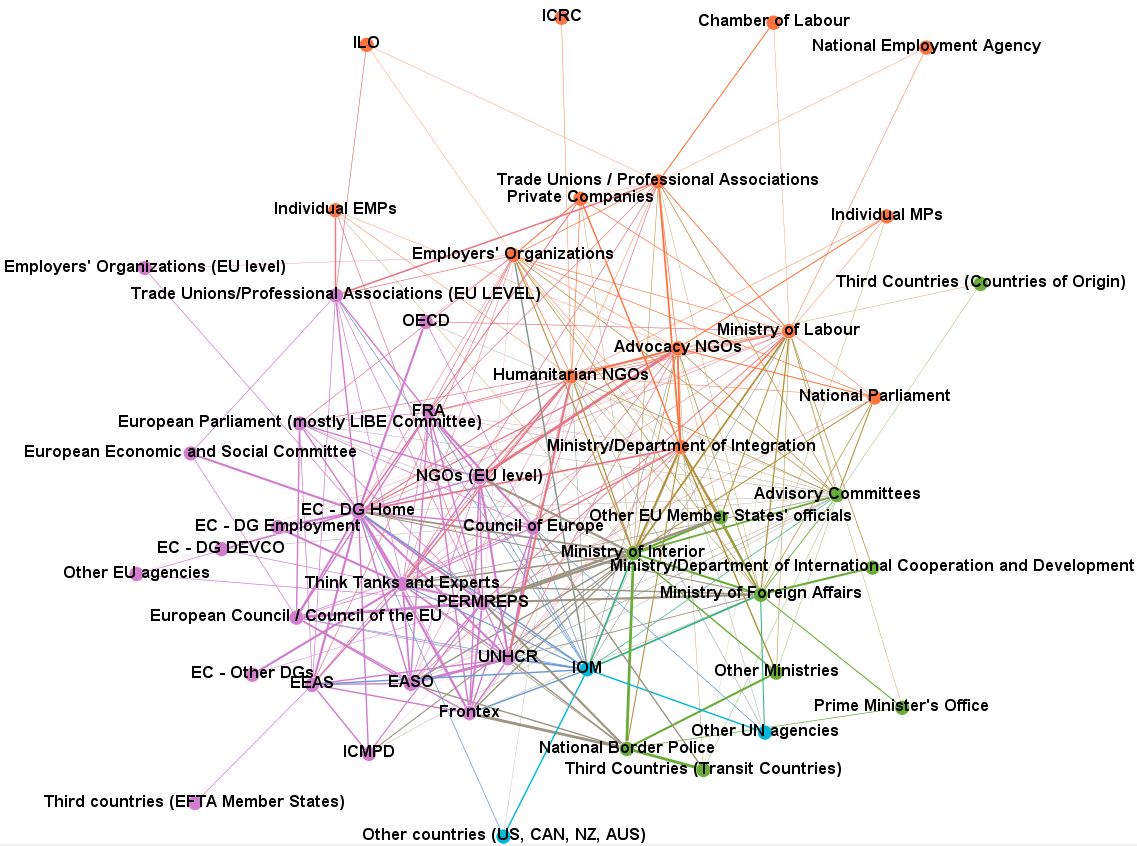

In our article we argue that one key to understanding this “status quo” tendency is looking at policy networks in the migration policy field. In particular, we tried to understand who the most influential actors are, how actors interact and exchange ideas and information, and what shapes their ideas about migration (causes and effects) and how to respond to migration.

To get insights to answer these questions, as part of the European Research Council (ERC) project Prospects for International Migration Governance (MIGPROSP), we interviewed key migration policy actors in major immigration receiving states in the EU, and in EU institutions between 2014 and 2018. During these interviews we collected data about

- the frequency of interviewees’ exchanges related to immigration with other policy actors,

- how valuable these exchanges are for them, and

- how similar or different they perceive the views on migration of these actors to be compared to their own (framing consonance).

We also collected data on information sources these actors use in their work. Applying Social Network Analysis, we could make three observations that are crucial to understand this current “status quo tendency”.

#1 – Home Affairs Actors have remained the most influential actors

First, our analysis confirms that EU migration policymaking over time has become increasingly complex and now involves a high number of actors and levels. However, our data shows that Interior Ministries and the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs (henceforth: Home Affairs actors) are still the most powerful actors within the policy network. They are the most central actors and they have the highest influence in the network. Their perspective or view on migration is dominant within the policy system.

But what about “new” actors that have entered the scene with (potentially) alternative perspectives on migration, such as international organizations, NGOs, trade unions, employers’ organizations, private companies, think tanks, and experts? Are they able to reach Home Affairs actors in a meaningful way, that would bring these alternative perspectives centre stage?

#2 – Exchanges between dominant home affairs actors and other actors are infrequent and shaped by different views of migration

Our data suggest that Home Affairs actors consider exchanges with these new actors as valuable. However, exchanges between Home Affairs actors and these “new” actors are occasional or less than occasional, with the partial exception of IOM and UNHCR. Furthermore, the perspectives of these “new” actors on migration issues are mostly perceived by Home Affairs actors as different or very different to their own perspectives. This is important because the literature has shown that in order for knowledge and ideas to transfer between actors, exchanges and contacts between these actors need to be frequent, and the underlying perspectives of the actors need to be perceived as compatible or aligned. More precisely, our data show that policy actors (and particularly Home Affairs actors) tend to interact more intensively and fruitfully with actors within their own circle, that are perceived as like-minded or sharing similar perspectives, rather than with actors with different views.

#3 – Powerful migration actors largely only get their information from internal, trusted sources

Finally, our data suggest that the “new” actors are not among the key sources of information that Home Affairs actors use to make decisions. We find that Home Affairs actors primarily rely on internal sources (i.e. sources within their own institutions) such as staff on the ground, agencies, and advisory boards to get information about migration. Some Home Affairs actors also mentioned that their key sources include reports or information produced by other Home Affairs actors (e.g. reports from EU agencies, DG Home, information exchanged with Member State officials etc.) and – to a lesser extent – material produced by IOM and UNHCR. Conversely, other types of sources such as reports from think tanks, academic sources, and reports from other international organizations, are very rarely or never mentioned. Reports produced by NGOs eventually are not taken into account at all, our data suggests.

What will drive of migration policy?

Our findings suggest that in addition to other explanations previously proposed by scholars, the current “status quo tendency” in the EU can be also understood as a result of policymakers’ patterns of interaction within the EU migration policy network. These interactions shape how dominant actors form understandings of policy problems and are shaped by dynamics of trust, of cognitive and organizational proximity, and of perceptions of like-mindedness that constrain transfers of knowledge and ideas between policy actors.

Our data emphasizes, that in order to understand migration policy we need to pay more attention to policy actors’ networks. Future research should hence further explore network dynamics focusing on different world regions and different policy sub-fields in order to understand this complex policy field.