Read more

Blog, Migration Governance

African and European migration diplomacy: a checklist and suggested future direction

While EU member states and citizens debate the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum, it is clear that migration has been, is and will continue to be an integral part of the relations...

In several countries, schools have remained closed and may operate at partial capacity in the next academic year. This will harm the academic progress and well-being of many children, but especially of those that already face many disadvantages. One such group is immigrant-origin students whose mother tongue differs from the language of instruction. The lack of in-school and continuous education could severely interfere with their language learning and have critical consequences for their academic progress and social inclusion.

Language barriers are one of the largest adversities faced by immigrant-origin students (that are foreign-born and/or with foreign-born parents). Fluency in the language of instruction is essential for them to make the most of educational opportunities and participate in the social life of their community.

The size of language barriers differs across groups of non-native speakers according to their linguistic background and whether they were born in the host country or arrived at a late age (among other factors). Therefore, targeted and intensive teaching is often necessary for certain students, but may not be available in schooling at the time of COVID.

In most educational systems, at a certain age, students are selected into different tracks mostly based on their academic performance. Educational tracks shape students’ academic and professional future. For example, in many countries, only certain tracks of upper secondary education grant access to university. Building fluency in the host language before the age of selection into educational tracks is crucial for immigrant-origin students to develop their full potential. Losing precious in-class teaching may be particularly detrimental for immigrant-origin students that are approaching key turning points in the educational system.

Language barriers in practice

The size of language barriers varies depending on the students’ mother tongue and the language of instruction. For example, the linguistic difficulty experienced by Spanish-speaking immigrants in Italy likely differs from the one they would face if they settled in Norway. This is because Spanish and Italian, unlike Spanish and Norwegian, share many lexical, grammatical and phonological characteristics.

When two languages share certain features, second language learners can transfer them from their first to their second language instead of learning them anew. As a result, linguistic barriers tend to be lower for language learners whose mother tongue is more similar to the language of instruction. Language barriers may also be exacerbated by other factors. For example, foreign-born students who settle into the host country at a late age tend to experience more difficulties in learning the new language.

Immigrant-origin students facing lower linguistic barriers can develop proficiency in the language of instruction more quickly. Cognitive processes associated with learning are facilitated when students are fluent in the language of instruction and they can make the most of learning opportunities.

Measuring the effects of language barriers on academic performance

In a recent paper, Dr. Francesca Borgonovi and I quantified how the academic outcomes of non-native-speaking immigrant-origin students depend on the dissimilarity between their mother tongue and the language used for instruction (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1041608020300911).

We used data on non-native-speaking immigrant-origin students from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) gathered by the OECD. Our study had a sample of over 20,000 students of age 15 in over 30 countries and speaking over 50 different languages. We measured the degree of dissimilarity between students’ native language and their language of instruction using a widely used index developed by the Automatic Similarity Judgement Program (ASJP). Our analyses controlled for several background characteristics to isolate the effect of language barriers from other factors such as cultural barriers or socio-economic hardship.

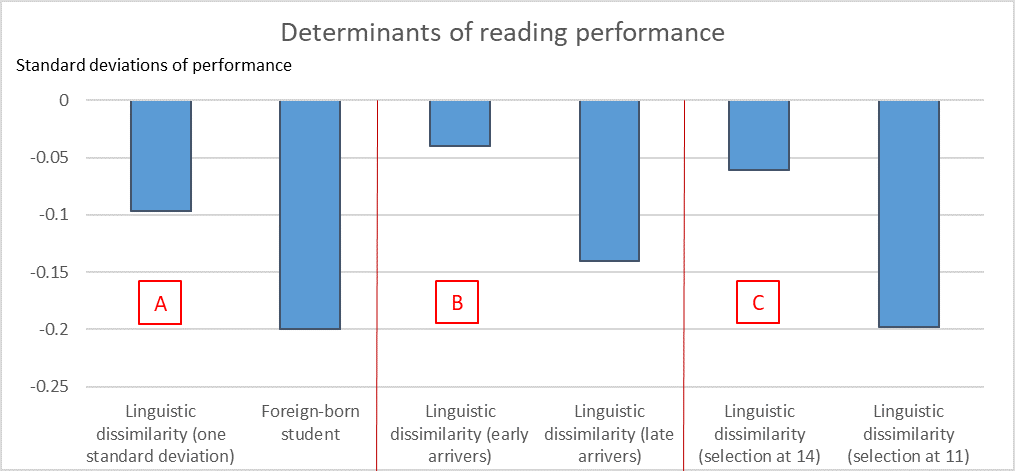

The figure below summarizes the main findings of the paper. An increase of one standard deviation in the linguistic dissimilarity index was associated with a decrease in students’ PISA reading performance of one tenth of a standard deviation (Panel A).

To explain the significance of this result, we compared this linguistic penalty to the disadvantage experienced by foreign-born students, who tend to be the most disadvantaged group of immigrant-origin students. Consider an example of two students born in England from foreign parents, one being a native German speaker and the other a native Vietnamese speaker. All things equal, the academic disadvantage experienced by the Vietnamese speaker compared to the German one is similar to the disadvantage from being a foreign-born student.

We also found that for foreign-born students, the negative effects of linguistic dissimilarity were almost three times as large for “late arrivers” (who arrived to the host country after the age of 11) compared to “early arrivers” (Panel B). In line with the “Critical Age Hypothesis”, compensating for a large dissimilarity between the mother tongue and the language of instruction appears to be harder after the age of 11-12.

We also found evidence that the negative effects of language barriers were greater in educational systems where students are selected into different tracks at a younger age (Panel C). In systems where students are placed into different tracks already at age 11 (such as Germany), language penalties were almost four times larger than in systems that selected students at age 14 (the majority of countries). In systems with later tracking, students have more time to compensate for large linguistic disadvantages before they are selected into more or less prestigious tracks.

No child left behind

Immigrant-origin students have very different experiences learning a new language based on their linguistic, cultural and economic background. Language support requires accurate and constant assessment of students’ language skills as well as targeted support guided by the specific difficulties each student may encounter.

The COVID pandemic has caused great upheaval and disruption in schooling. It is often the case that most disadvantaged students are hardest hit by such adverse events. Among these, are immigrant-origin students who must overcome many adversities, such as language barriers. Schools are adjusting to a complex situation that will require creative and expensive solutions. Special attention must be devoted to the most disadvantaged students to in order to make sure that no child is left behind.

Alessandro Ferrara, PhD researcher, Department of Political and Social Sciences, EUI

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.