Read more

Blog, Migration Governance

Emerging themes from MIGPROSP research

We’re now two years into the MIGPROSP project and have conducted more than 200 interviews with “actors” in migration governance systems in Asia-Pacific, Europe, North America and South America. By actors we mean those...

https://youtube.com/watch?v=yrpOypbRrp0

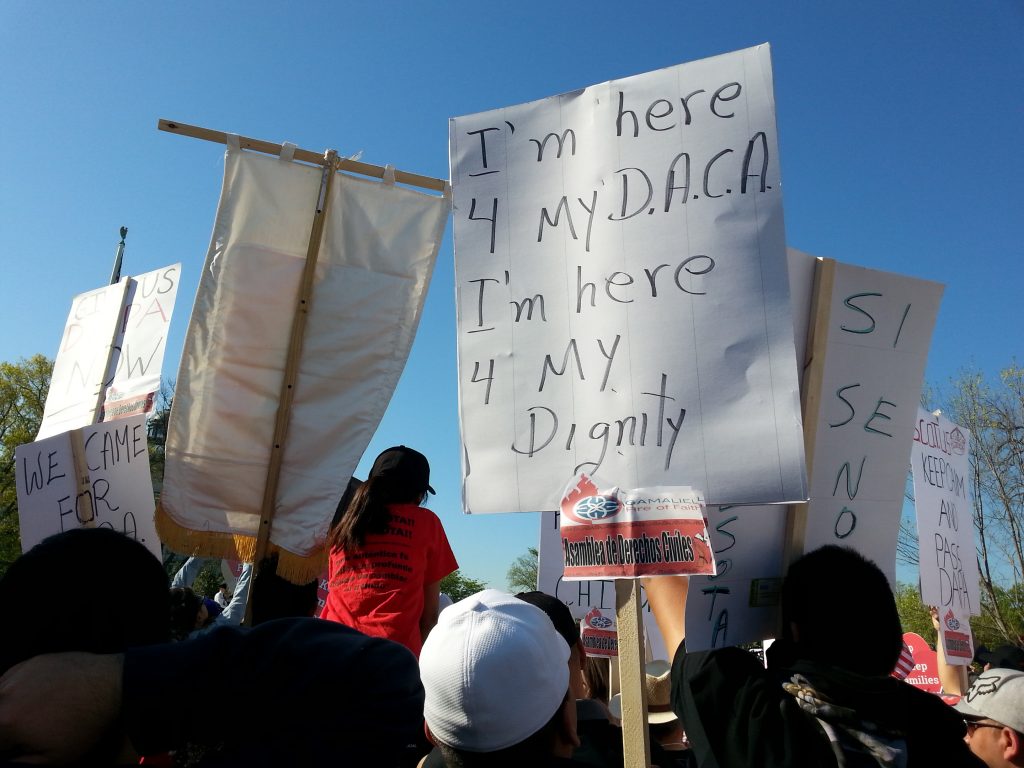

The phrase ¡Si Se Puede! (commonly translated from Spanish as Yes, it can be done! or Yes, we can!) has been the slogan for Latino related movements in the United States for many years. It has now recently been chanted by the more than 1000 protesters in front of the US Supreme Court on 18 April 2016. The court heard arguments in the case United States vs. Texas, a suit initially brought by Texas and 25 other US states with the intention to stop Deferred Action for Parental Accountability (DAPA) – Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents.

Children and families amid lack of comprehensive immigration reform

Deferred Action is a procedure which awards immigration authorities the discretion to refrain from deporting an undocumented immigrant on a case-by-case basis. DAPA provides deferred action for undocumented individuals who are parents of children who are US citizens or lawful permanent residents. It is similar to DACA – Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals – which was announced in 2012 and provides discretionary relief from deportation for individuals who meet a set of criteria and who were unlawfully brought to the United States as children. In November 2014, the Obama Administration issued an executive action on immigration which expanded DACA and initiated DAPA.

While the original DACA programme is accepting applications, DAPA and the expanded DACA have been placed on hold by the issuance of an Order of Temporary Injunction by a federal district judge on 16 February 2015.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that the DAPA and extended DACA programs could provide relief for more than 5.2 million people, which is assumed to be almost half of the unauthorized population in the United States. The L.A. Times reports that two thirds of the more than 11 million unauthorized immigrants have been living in the US for more than ten years and “are a part of our society”. Due to the absence of comprehensive immigration reform, an estimated 16.6 million people live in mixed-status families, where one or both parent(s) might be unauthorized but the children might have been born in the US and are therefore citizens. In some families, siblings might not have the same legal status. In some cases the older children in a family are unauthorized, having been born abroad and brought to the US by their parents, but their younger siblings are US citizens, having been born in the United States.

The constant threat of deportation faced by unauthorized individuals has particular implications for mixed-status families. When an undocumented parent is deported, their parental rights are terminated and the US citizen child is placed in foster care. In some cases, the primary provider of the family is deported, which leaves the other parent, often the mother, struggling to survive. Understandably, these kinds of events are very traumatizing for the individuals involved. In the absence of comprehensive immigration reform, policies like DAPA and DACA could provide options for those families and other undocumented individuals. The issue has become particularly significant in recent years because the administration has increased the number of deportations, as highlighted by a report by the Center for American Progress from 2012.

But when President Obama announced DAPA and the DACA expansion, some questioned whether the President had overstepped his authority. This is what the Supreme Court will decide in US v. Texas. The judges’ primary focus is on four legal questions:

- Do the 26 states have the legal standing they need for suing the federal government in this case?

- Did the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issue the guidance in accordance with procedures required by law?

- If DHS issued the DAPA and expanded DACA guidelines in the right way, were the programs’ provisions legal for the executive branch to draft, or is the right reserved for Congress?

- Were the guidelines not only illegal, but unconstitutional?

The ruling is expected to be issued during the summer.

Immigration policy since the 2014 child migrant crisis

The Executive Action of November 2014 had been preceded by a large increase in the number of children migrating to the United States. Most of the children were from the Northern Triangle Central American countries (NTCA) – Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. A total of 68,000 children were apprehended by immigration authorities during 2014, the majority in the Rio Grande Valley, TX. The US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) found it challenging to accommodate the minors in accordance with the law, prompting criticisms from various actors of the administration. The phenomenon is now commonly referred to as the 2014 child migrant crisis or US south-west border crisis.

Child migrants are defined as individuals who are: 1) under the age of 18, 2) lack temporary or permanent legal status and 3) are without a parent or otherwise legal guardian to care for them. While they aren’t one of the groups directly affected by DACA or DAPA, these policies represent actors’ efforts towards advancing the rights of migrant children and unauthorized immigrant families. How successful the movement is remains to be seen.

When I travelled for MIGPROSP to the United States in April and early May of 2016 this year I spoke with more than 30 actors in US child migration governance, including members of government and of immigrant rights advocacy organizations. The interviews were conducted as part of an on-going research study on how actors frame issues surrounding child migration, and how these frames might help shape policy outcomes. I asked actors about their perceptions and understanding of child migration and the policy environment. The remainder of this blog presents some of my preliminary findings on the position of civil society in US child migration governance.

Civil Society in U.S. Migration Governance: Position, Successes and Uncertainties

Everyone I interviewed considered immigrant rights groups and other advocacy organizations to be important actors. In the wake of the increase in numbers and the government’s challenges in responding to the influx, civil society organizations have stepped in by offering important services to the minors. Faith-based organizations have been contracted by the government to provide housing and/or assist in finding sponsors for the children. Legal advocacy organizations aim to fill the lack of government funded legal representation through the coordination of pro-bono networks. By providing these services, civil society organizations work closely with child migrants themselves — so they have a unique understanding of the issue.

Both state and non-state actors report that there is a strong, ongoing relationship between them. Members of civil society felt that they have regular contact with members of government, that their opinions are heard and that they have generally good access. Several members of government reported that they value the organizations’ expertise and on-the-ground perspectives. While some mentioned that they will probably never be able to satisfy all the demands of civil society, they welcome their feedback on how to treat migrants more humanely while they are going through immigration proceedings.

But when actors were asked about how they would rate civil society’s degree of influence on policy outputs, opinions varied. One member of a faith-based organization confidently stated that they are one of the most influential actors in child migration governance. Another actor supported this by pointing out that some very senior members of Congress have strong, long-standing relationships with faith-based groups. Other members of civil society organizations admitted that, while they feel they have very regular and easy access to governmental actors, and are listened to, it is difficult to say what happens behind closed doors. They were unsure how much weight is given to their requests and positions in the drafting of laws and policies.

In addition, civil society does not exclusively c omprise immigrant advocacy organizations. A number of organizations that are active on Capitol Hill lobby for more restrictionist immigration policies. According to MIGPROSP interview data, actors perceive these organizations to be far fewer in number than advocacy groups. Yet their presence is strongly felt with frequent appearances on the news and regular testimonies in front of Congress.

omprise immigrant advocacy organizations. A number of organizations that are active on Capitol Hill lobby for more restrictionist immigration policies. According to MIGPROSP interview data, actors perceive these organizations to be far fewer in number than advocacy groups. Yet their presence is strongly felt with frequent appearances on the news and regular testimonies in front of Congress.

Nonetheless, several actors felt that the advocacy community has been able to achieve some important milestones in advancing the rights of child migrants. These include the Flores Settlement of 1997 of 1997, which established more child-friendly criteria for detaining unaccompanied children; the transfer of custody of child migrants from immigration authorities to the Department of Health and Human Services — which is better equipped to deal with vulnerable populations — under the Homeland Security Act of 2002; and the Trafficking Victims Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2008, which implemented screening of children for possible protection needs.

Whether this trend of advancing child migrants’ rights will continue has been called into question by recent policy developments since the south-west border crisis of 2014. The field of child migration governance is now plagued by many uncertainties. There are currently several proposals pending in Congress. These include the Fair Day in Court Act, which would grant child migrants the right to government funded legal representation and which has been championed by civil society. But there is a fear that other bills might strip child migrants of existing rights in the hope of deterring future flows. Which of these proposals — if any — will pass Congress remains to be seen. In addition, developments in other areas of immigration, such as the outcome of the DAPA Supreme Court case, may have important implications. Actors are also wary of the outcome of the 2016 presidential elections. Members of immigrant rights groups are determined to continue their advocacy, hoping to be able to show affected communities that !Si Se Puede¡