Read more

Blog, Public Attitudes

International cooperation: does migration have a centrifugal or centripetal influence?

Recent political developments might suggest that migration-related issues entail centrifugal tendencies for matters of international cooperation, in that they appear to involve fragmentation and disengagement from wider forms of cooperation. But, can migration also...

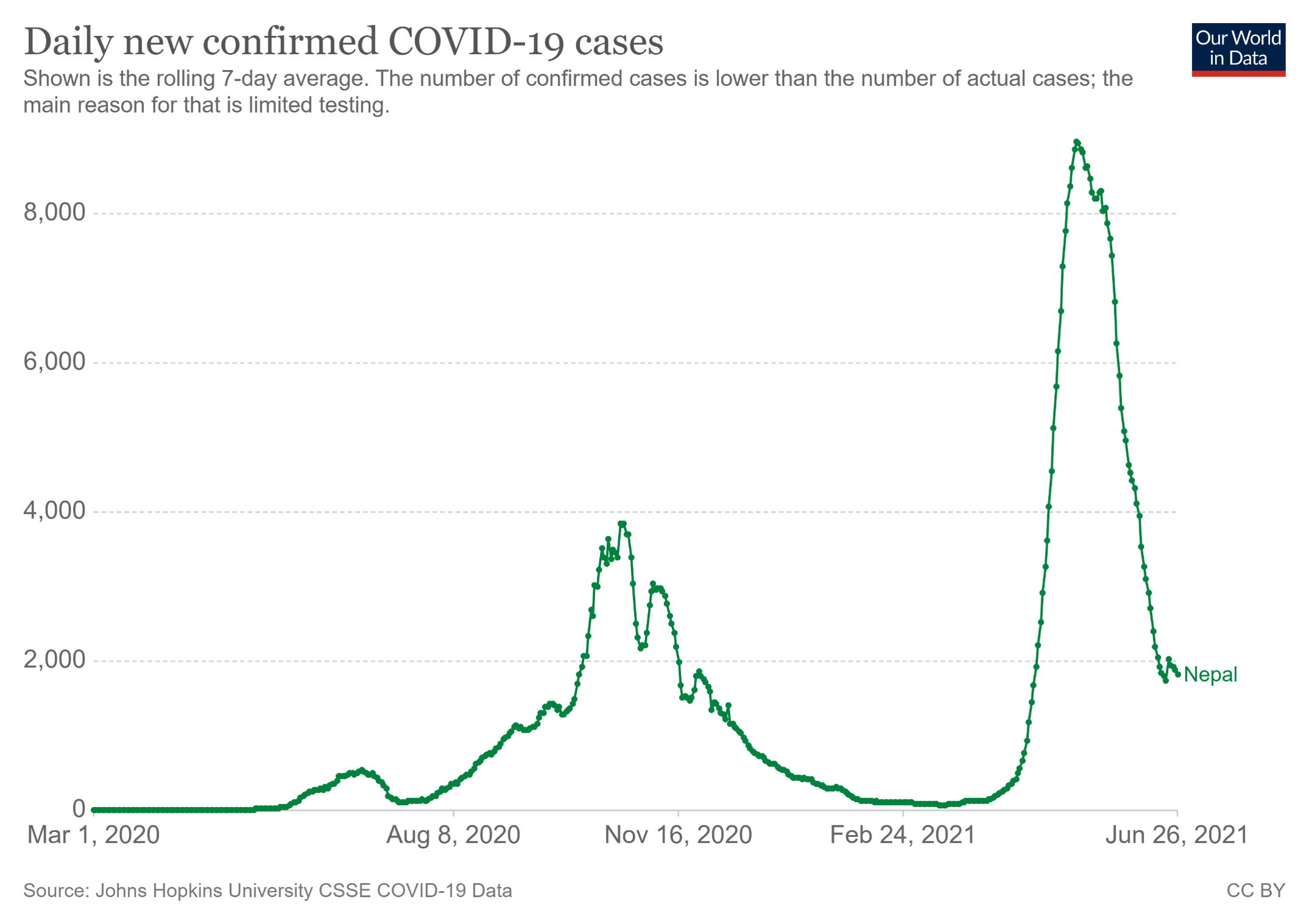

As detailed in a blog post “COVID-19 and Reverse Migration in Nepal” from last June, there was much uncertainty about the impact of COVID-19 on Nepal’s migrants amid the health risks, lockdown and flight bans. Stranded migrants abroad pressured the Nepal Government for repatriation support, either because they had lost jobs or due to fear of virus exposure in cramped living and work settings. With Nepal itself grappling with rising cases and a beleaguered health system, safely repatriating thousands of returnees daily posed a significant challenge. The Government had to undertake a massive repatriation exercise to bring home migrants on a priority basis from multiple destination countries. Government estimates show that in the last 14 months, over 460,000 Nepalis have returned either via repatriation or regular flights, which includes regular returnees as well as those impacted by COVID-19. After a brief window with some semblance of normalcy including a slow recovery of foreign emigration, Nepal has again been gripped by a second wave fueled by a more lethal and transmissible delta variant since March (see Figure 1). International migration is once more back into the throes of uncertainty with the lives of thousands of Nepali migrants, both current and aspirants, upended.

Figure 1: Daily new confirmed COVID-19 cases

Deployment of Workers in Uncertainty

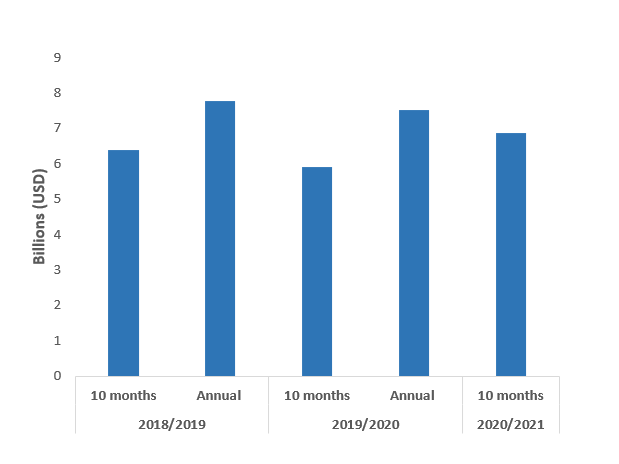

In August 2020, after a five-month halt, the Government of Nepal resumed issuing labor approvals which are mandatory for migrants to exit the country. Foreign employment was slowly picking up, albeit significantly lower than pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 2). Between August-March 2020 before the onset of the second wave, over 72,000 migrants received labor approvals, a 72 per cent drop compared to the same period the previous year. At a bilateral level, the resumption of deployment was uneven, depending on a range of factors like the foreign admission policy of the destination country or the policies by Nepali Diplomatic Missions abroad regarding new job demand verification. For example, the Malaysian Government has indefinitely barred recruitment of new foreign workers while the UAE issued visas only for employment in semi-government organisations. With the onset of the second wave in Nepal, while the Government continued to issue labor approvals other than in May, flight bans have left thousands of Nepalis stuck.

The lives-versus-livelihood dilemma extends beyond borders, and current and aspirant migrants unable to start or resume their overseas employment have found different channels to express their frustration. A high profile case is that of Ajay Sodari, who has captured public attention in Nepal after organizing multiple protests in Kathmandu amid the pandemic to pressure the Nepal Government to facilitate their employment to South Korea which has been halted for the last 13 months due to the pandemic: first because of Nepal’s ban on commercial flights, and later because Korea stopped issuing visas to Nepalis due to public health concerns. Like 10,000 other Nepalis, Sodari is eligible to work in South Korea under the popular Government to Government (G2G) Employment Permit Scheme (EPS) after a grueling testing and screening process that takes multiple years of preparation. After the country went into lockdown, the protest has moved online to social media with twitter hashtags like “#justiceforepspasser” by stranded EPS aspirants trending in Nepal. Like South Korea, Nepal is also on the red list of multiple other countries such as the UAE, Bahrain, Malaysia and Oman.

Figure 2: Labor Approvals Received by Nepali Migrants (for new and continued employment)

Source: Department of Foreign Employment

Inadequate Diplomacy and Coordination

Even as the second wave is subsiding and flights are slowly resuming, deployment of outgoing workers in the near future is rife with challenges. Multiple countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait have announced mandatory vaccine for all incoming travelers from August, but for countries like Nepal that are bearing the brunt of global vaccine inequality with only 2.55 per cent of the population doubly vaccinated, it is uncertain when migrants will get their turn. Even if outgoing migrants were to be included in priority groups for vaccine, many destination countries do not recognise the Chinese Sinopharm vaccine that is being administered in Nepal. There are also concerns regarding quarantine and testing requirements, and who bears the associated costs. Temporary labor migration from South Asia is characterized by high recruitment costs that can take many months out of a two-year contract to recuperate, and additional costs being passed down on workers further dampens the benefits of migration. While thousands of Nepalis abroad have benefited from vaccinations provided by the destination countries, there are also concerns about the inclusiveness of irregular migrants in vaccination drives. For example, Malaysia has recently intensified crackdowns on undocumented workers amid surging cases, an action that can potentially push irregular workers further into the shadows out of fear of repercussion. These added, new complexities brought on by COVID-19 requires more diplomatic dialogue in migration management. While these challenges are not unique to Nepal alone but to other sending countries as well, existing regional platforms like the Abu Dhabi Dialogue and the Colombo Process to raise shared concerns among sending and receiving countries have been largely inactive.

Beyond vaccines, there is also a need for more proactive diplomacy to promote labor market opportunities, skills partnerships and worker welfare which requires well-trained diplomats who can leverage the proximity advantage to engage in negotiations and cooperation with host Government counterparts, employers and their associations. A good example in the midst of the pandemic was a pilot program between Governments of Nepal and Israel for the recruitment of 500 Nepali caregivers under the G2G model for placement in old age homes sets good precedence. In addition to attractive employment terms, the program also opens up opportunities for Nepali women who have been unable to reap the benefits of emigration and account less than 10 per cent of total migrants. Such sector specific, practical partnerships need to be further prioritised given their contributions to migrants and their families as evidenced by evaluations from Malaysia , South Korea , the US and New Zealand.

Foreign Employment Industry in Perils

Private recruitment agencies responsible for over 85 per cent of migration from Nepal are heavily impacted by the pandemic. Recruiters in Nepal faced a complete halt in their business for several months, and resumption has been slow and uneven. In February, for example, only 330 of the active 853 recruiters were able to mobilise workers with 193 mobilising just ten workers or fewer. However, due to malpractices such as high recruitment costs and cases of contract substitution, recruiters have garnered a poor reputation that obscures their immense contribution in matching hundreds of thousands of workers annually including from some of the remotest corners of Nepal with foreign employers. The balance between facilitating and regulating recruiters is delicate, but their contributions cannot be overlooked. Alongside regulatory efforts to curb malpractices, cooperating with the private sector is imperative to identify new job opportunities, diversify to new countries or new sectors with demand for workers in this new context and to revive emigration which is an important policy priority.

Licensed recruiters, for example, are required to meet certain requirements such as minimum escrow deposits and minimum annual deployment target to continue operations as detailed in the Foreign Employment Act and Rules. But with the current economic fallout induced by the pandemic, recruiters are demanding that a few of these restrictions be revisited so they don’t have to shut down business. During a crisis of this scale, responsive policymaking also means responding to reasonable demands of recruiters, a key stakeholder, which hasn’t been the case so far.

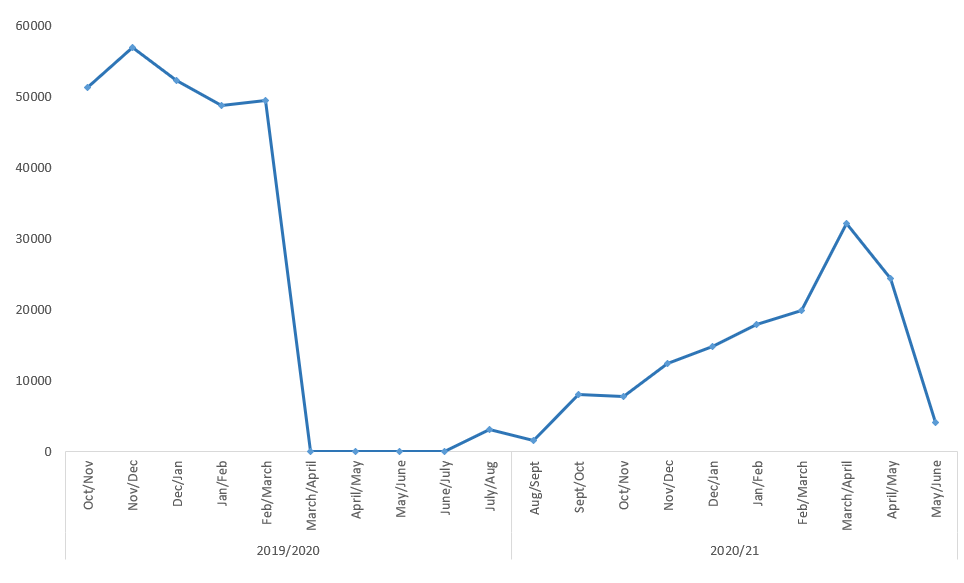

More than Remittances

Despite the flip-flopping of health and foreign worker policies and the uncertainty, remittance which is equivalent to over a quarter of Nepal’s GDP has remained strong. Contrary to predictions of steep remittance drops by as much as 14 per cent by the World Bank, remittances fell by a marginal 0.5 per cent in Nepali Rupees and 3.3 per cent in USD in FY 2019/20 (see Figure 3). This is attributed to a combination of factors including the formalisation of informal transfers, the engagement of Nepalis in essential sectors abroad and migrants remitting their savings and end of service benefits. The Nepal Government does not release data on bilateral remittance which prevents a more nuanced analysis of the impact of COVID-19. Furthermore, the optimistic macro picture also obscures individual realities of migrants for whom a disruption to this vital income source with very little formal support in Nepal has had grave consequences.

Figure 3: Incoming Remittances in USD

Beyond remittances, Nepalis have also collectively extended critical, life-saving support to Nepal. For example, migrants in the Middle East were some of the first to send 560 oxygen cylinders to Nepal under a campaign called “Send oxygen to Nepal and save lives” that crowd-funded donations from thousands of migrants from each Gulf Corporation Council country. Nepali migrant associations responsible for these support initiatives share that the first wave entailed helping stranded Nepalis abroad whereas during the second wave, with things relatively calmer in the destination country, migrant associations have been able to focus their efforts on helping Nepal.

The pandemic has cast migration in a different light. In the destination country, the occupational categories occupied by temporary migrants traditionally considered “low-skilled”, whether in sectors like cleaning, security, storekeeping, PPE manufacturing or domestic work, are being viewed as “essential” during the pandemic. In sending countries like Nepal, the subsequent remittances from these very workers have been a critical lifeline, with migrants also going beyond financial remittances to support their homeland via philanthropic initiatives as it reels through yet another COVID-19 wave.

Upasana Khadka, consults for the World Bank and is a Columnist for the Nepali Times.

The EUI, RSCAS and MPC are not responsible for the opinion expressed by the author(s). Furthermore, the views expressed in this publication cannot in any circumstances be regarded as the official position of the European Union.