-

-

Andrew Geddes

Full-time Professor

Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies

Director

Migration Policy Centre

Read more

Blog, Labour markets & welfare states

What do trade agreements have to do with migration policy?

Preferential trade agreements (PTAs) aim to facilitate trade between two or more countries by doing things such as cutting tariffs or facilitating investment, but new research from the University of Geneva shows that that...

New research from the Migration Policy Centre shows continued high levels of public support in eight European countries for refugees from Ukraine since the full-scale Russian invasion. Europeans remain strongly supportive of Ukrainian refugees with little sign so far of ‘compassion fatigue’ setting in, at least so far as Ukrainian refugees are concerned. The picture is different for refugees from other parts of the world.

About the study

We ran online, nationally representative surveys in eight countries (Austria, Czechia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia) last year in May and June 2022 and then again this year in April 2023. The survey also included an experimental component where it randomly allocated respondents to two equally sized groups within each national sample; one group was asked about Ukrainian refugees and the other group was asked the same set of questions but about Syrian refugees. This allowed us to identify differences in attitudes to the two groups.

What we found

1) Europeans’ support for Ukrainian refugees remains high, with little evidence of compassion fatigue setting in.

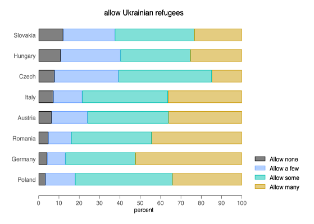

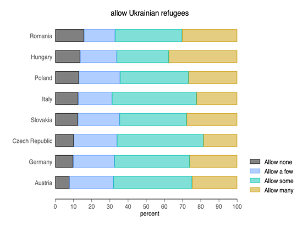

In 2022, our survey found high levels of support for Ukrainian refugees and so far in 2023, this support has been broadly maintained. There are some variations, but the pattern is quite clear: the majority of respondents in all eight of the surveyed countries still support allowing ‘many’ or ‘some’ Ukrainian refugees to come and live in their country.

Figure 1: Levels of support for Ukrainian refugees 2022 (top) versus 2023 (bottom)

A concern could be that EU citizens become weary of the scale of displacement and its implications for example for public services, but thus far there is little evidence to suggest that compassion fatigue is setting in.

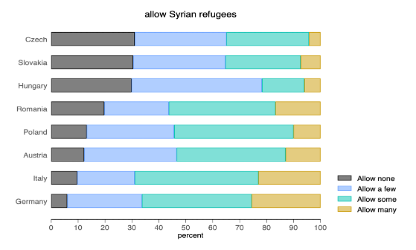

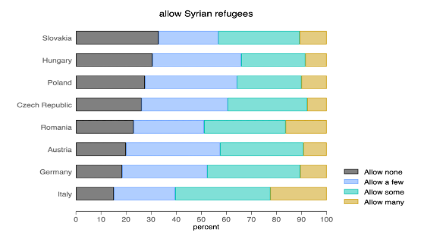

Is this largely consistent support for displaced Ukrainians matched by support for refugees from other countries? The short answer is no. When we looked at the group of respondents only asked about how many Syrian refugees should be allowed into the country, we found lower support for Syrian refugees in 2023 compared to 2022, especially among the Western European countries in our sample.

Figure 2: Levels of support for Syrian refugees 2022 (top) versus 2023 (bottom)

2) Levels of support for Syrian refugees are consistently lower than levels of support for Ukrainian refugees

Not only have levels of support dropped for Syrian refugees between this year and last, but when we compare attitudes between our two groups of survey respondents, we find that levels of support for Syrian refugees are consistently lower than support for Ukrainian refugees (with the exception of Italy who in 2023 is the only country in our survey where there is no statistically significant difference between attitudes to Syrian and Ukrainian refugees). Lower levels of support for Syrian refugees is particularly evident in the Central European countries that we surveyed.

This finding is surprising; the expectation would be that countries that previously had very low levels of public support for refugees, like Central European countries did, would also be opposed to large scale influxes of refugees and therefore would not show strong support to the influx of Ukrainian refugees. However, our findings run contrary to this expectation because we find high and sustained levels of support for Ukrainian refugees in both Central and West European countries. What could account for this?

3) Perception of Russia as a threat drives support for Ukrainian refugees.

It is possible that the perceived lack of ethnic or religious similarity or affinity could explain the lower levels of support for Syrian refugees in Central Europe. However, our data do not allow us to disentangle precisely what specific factors about Syrian compared to Ukrainian refugees might be driving these differences— whether it is the perceived ethnicity or religion or perhaps the gender of the two refugee groups or all of these at the same time.

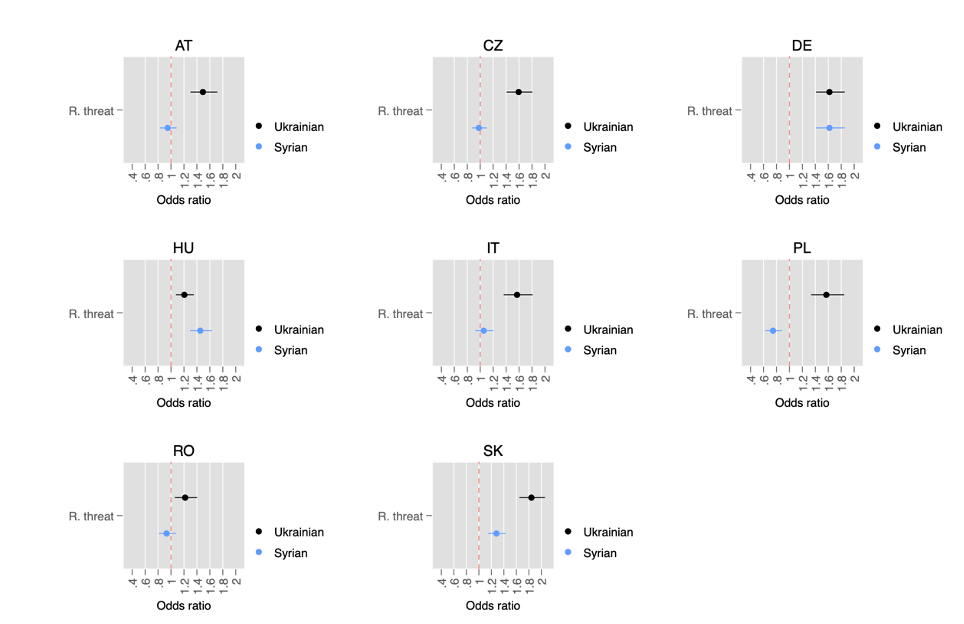

However, what we do find in Central European countries that is distinct from Western European countries is the role played by the perception of Russian threat; in all Central European countries with the exception of Hungary, this plays a powerful role in driving support for Ukrainian refugees and, conversely, the relative lower levels of support for Syrian refugees. This effect is shown in Figure 4 which shows odds ratios for all 8 countries to quantify the association between perception of Russian threat and support for Ukrainian refugees. In short, the further to the right of the red dotted line are the blue and black dots then the stronger is the association between support for refugees from Ukraine and Syria and perception of Russian threat.

Figure 3: Perception of Russia as a threat drives support for Ukrainian refugees.

This perception of Russian threat in Central Europe seems highly likely to be connected to historical memory of the Soviet era and highlights the important role geopolitical and historical factors can play as drivers of attitudes to refugees.

Why this matters

In the 16 months since the full-scale Russian invasion, we find strong and sustained support for Ukrainian refugees in all eight of the countries that are surveyed. This has clearly been helped by the strong support for the Ukrainian resistance to the Russian aggression from almost all EU member states. There can be little doubt in the minds of most Europeans why Ukrainian people are being forced to flee and, also, why they are fleeing to neighbouring European countries in particular. This perception seems particularly evident in Central European countries where an uneasy feeling of ‘we might be next’ mixes with historical memory to activate strong support for displaced Ukrainians, but less so for refugees from other parts of the world.

The scale of displacement from Ukraine is huge: by mid-July 2023, 6.2 million Ukrainians had been forced to leave their country, of these, 5.28 million had moved to other European countries and more than 4 million had registered for protection under the EU’s Temporary Protection Directive. The scale makes it important to track and analyse attitudes to Ukrainian displacement because there is a high risk that this becomes a protracted situation. We also know that migration and asylum are rising in salience across Europe and could play a significant role in the 2024 elections to the European Parliament.